Introduction

A serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI), also known as a triple reuptake inhibitor (TRI), is a type of drug that acts as a combined reuptake inhibitor of the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. It does this by concomitantly inhibiting the serotonin transporter (SERT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), and dopamine transporter (DAT), respectively. Inhibition of the reuptake of these neurotransmitters increases their extracellular concentrations and, therefore, results in an increase in serotonergic, adrenergic, and dopaminergic neurotransmission. The naturally-occurring and potent SNDRI cocaine is widely used recreationally and often illegally for the euphoric effects it produces.

Other SNDRIs were developed as potential antidepressants and treatments for other disorders, such as obesity, cocaine addiction, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and chronic pain. They are an extension of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) whereby the addition of dopaminergic action is thought to have the possibility of heightening therapeutic benefit. However, increased side effects and abuse potential are potential concerns of these agents relative to their SSRI and SNRI counterparts.

The SNDRIs are similar to non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as phenelzine and tranylcypromine in that they increase the action of all three of the major monoamine neurotransmitters. They are also similar to serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agents (SNDRAs) like MDMA (“ecstasy”) and α-ethyltryptamine (αET) for the same reason, although they act via a different mechanism and have differing physiological and qualitative effects.

Although their primary mechanisms of action are as NMDA receptor antagonists, ketamine and phencyclidine are also SNDRIs and are similarly encountered as drugs of abuse.

Indications

Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the foremost reason supporting the need for development of an SNDRI. According to the World Health Organization, depression is the leading cause of disability and the 4th leading contributor to the global burden of disease in 2000. By the year 2020, depression is projected to reach 2nd place in the ranking of DALYs (disability-adjusted life year).

About 16% of the population is estimated to be affected by major depression, and another 1% is affected by bipolar disorder, one or more times throughout an individual’s lifetime. The presence of the common symptoms of these disorders are collectively called ‘depressive syndrome’ and includes a long-lasting depressed mood, feelings of guilt, anxiety, and recurrent thoughts of death and suicide. Other symptoms including poor concentration, a disturbance of sleep rhythms (insomnia or hypersomnia), and severe fatigue may also occur. Individual patients present differing subsets of symptoms, which may change over the course of the disease highlighting its multifaceted and heterogeneous nature. Depression is often highly comorbid with other diseases, e.g. cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, stroke), diabetes, cancer, Depressed subjects are prone to smoking, substance abuse, eating disorders, obesity, high blood pressure, pathological gambling and internet addiction, and on average have a 15 to 30 year shorter lifetime compared with the general population.

Major depression can strike at virtually any time of life as a function of genetic and developmental pre-disposition in interaction with adverse life-events. Although common in the elderly, over the course of the last century, the average age for a first episode has fallen to ~30 years. However, depressive states (with subtly different characteristics) are now frequently identified in adolescents and even children. The differential diagnosis (and management) of depression in young populations requires considerable care and experience; for example, apparent depression in teenagers may later transpire to represent a prodromal phase of schizophrenia.

The ability to work, familial relationships, social integration, and self-care are all severely disrupted.

The genetic contribution has been estimated as 40-50%. However, combinations of multiple genetic factors may be involved because a defect in a single gene usually fails to induce the multifaceted symptoms of depression.

Pharmacotherapy

There remains a need for more efficacious antidepressant agents. Although two-thirds of patients will ultimately respond to antidepressant treatment, one-third of patients respond to placebo, and remission is frequently sub-maximal (residual symptoms). In addition to post-treatment relapse, depressive symptoms can even recur in the course of long-term therapy (tachyphylaxis). Also, currently available antidepressants all elicit undesirable side-effects, and new agents should be divested of the distressing side-effects of both first and second-generation antidepressants.

Another serious drawback of all antidepressants is the requirement for long-term administration prior to maximal therapeutic efficacy. Although some patients show a partial response within 1–2 weeks, in general one must reckon with a delay of 3–6 weeks before full efficacy is attained. In general, this delay to onset of action is attributed to a spectrum of long-term adaptive changes. These include receptor desensitization, alterations in intracellular transduction cascades and gene expression, the induction of neurogenesis, and modifications in synaptic architecture and signalling.

Depression has been associated with impaired neurotransmission of serotonergic (5-HT), noradrenergic (NE), and dopaminergic (DA) pathways, although most pharmacologic treatment strategies directly enhance only 5-HT and NE neurotransmission. In some patients with depression, DA-related disturbances improve upon treatment with antidepressants, it is presumed by acting on serotonergic or noradrenergic circuits, which then affect DA function. However, most antidepressant treatments do not directly enhance DA neurotransmission, which may contribute to residual symptoms, including impaired motivation, concentration, and pleasure.

Preclinical and clinical research indicates that drugs inhibiting the reuptake of all three of these neurotransmitters can produce a more rapid onset of action and greater efficacy than traditional antidepressants.

DA may promote neurotrophic processes in the adult hippocampus, as 5-HT and NA do. It is thus possible that the stimulation of multiple signalling pathways resulting from the elevation of all three monoamines may account, in part, for an accelerated and/or greater antidepressant response.

Dense connections exist between monoaminergic neurons. Dopaminergic neurotransmission regulates the activity of 5-HT and NE in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DR) and locus coeruleus (LC), respectively. In turn, the ventral tegmental area (VTA) is sensitive to 5-HT and NE release.

In the case of SSRIs, the promiscuity among transporters means that there may be more than a single type of neurotransmitter to consider (e.g. 5-HT, DA, NE, etc.) as mediating the therapeutic actions of a given medication. MATs are able to transport monoamines other than their “native” neurotransmitter. It was advised to consider the role of the organic cation transporters (OCT) and the plasma membrane monoamine transporter (PMAT).

To examine the role of monoamine transporters in models of depression DAT, NET, and SERT knockout (KO) mice and wild-type littermates were studied in the forced swim test (FST), the tail suspension test, and for sucrose consumption. The effects of DAT KO in animal models of depression are larger than those produced by NET or SERT KO, and unlikely to be simply the result of the confounding effects of locomotor hyperactivity; thus, these data support re-evaluation of the role that DAT expression could play in depression and the potential antidepressant effects of DAT blockade.

The SSRIs were intended to be highly selective at binding to their molecular targets. However it may be an oversimplification, or at least controversial in thinking that complex psychiatric (and neurological) diseases are easily solved by such a monotherapy. While it may be inferred that dysfunction of 5-HT circuits is likely to be a part of the problem, it is only one of many such neurotransmitters whose signalling can be affected by suitably designed medicines attempting to alter the course of the disease state.

Most common CNS disorders are highly polygenic in nature; that is, they are controlled by complex interactions between numerous gene products. As such, these conditions do not exhibit the single gene defect basis that is so attractive for the development of highly-specific drugs largely free of major undesirable side-effects (“the magic bullet”). Second, the exact nature of the interactions that occur between the numerous gene products typically involved in CNS disorders remain elusive, and the biological mechanisms underlying mental illnesses are poorly understood.

Clozapine is an example of a drug used in the treatment of certain CNS disorders, such as schizophrenia, that has superior efficacy precisely because of its broad-spectrum mode of action. Likewise, in cancer chemotherapeutics, it has been recognized that drugs active at more than one target have a higher probability of being efficacious.

In addition, the nonselective MAOIs and the TCA SNRIs are widely believed to have an efficacy that is superior to the SSRIs normally picked as the first-line choice of agents for/in the treatment of MDD and related disorders. The reason for this is based on the fact that SSRIs are safer than nonselective MAOIs and TCAs. This is both in terms of there being less mortality in the event of overdose, but also less risk in terms of dietary restrictions (in the case of the nonselective MAOIs), hepatotoxicity (MAOIs) or cardiotoxicity (TCAs).

Applications other than Depression

- Alcoholism (c.f. DOV 102,677)

- Cocaine addiction (e.g., indatraline)

- Obesity (e.g., amitifadine, tesofensine)

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (c.f. NS-2359, EB-1020)

- Chronic pain (c.f. bicifadine)

- Parkinson’s disease

List of SNDRIs

Approved Pharmaceuticals

- Mazindol (Mazanor, Sanorex) – anorectic; 50 nM for SERT, 18 nM for NET, 45 nM for DAT

- Nefazodone (Serzone, Nefadar, Dutonin) – antidepressant; non-selective; 200 nM at SERT, 360 nM at NET, 360 nM at DAT

- Nefopam (Ki SER/NE/DA = 29/33/531nM)

Sibutramine (Meridia) is a withdrawn anorectic that is an SNDRI in vitro with values of 298 nM at SERT, 5451 at NET, 943 nM at DAT. However, it appears to act as a prodrug in vivo to metabolites that are considerably more potent and possess different ratios of monoamine reuptake inhibition in comparison, and in accordance, sibutramine behaves contrarily as an SNRI (73% and 54% for norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition, respectively) in human volunteers with only very weak and probably inconsequential inhibition of dopamine reuptake (16%).

Venlafaxine (Effexor) is sometimes referred to as an SNDRI, but is extremely imbalanced with values of 82 nM for SERT, 2480 nM for NET, and 7647 nM for DAT, with a ratio of 1:30:93. It may weakly inhibit the reuptake of dopamine at high doses.

Coincidental

- Esketamine (Ketanest S) – anesthetic; S-enantiomer of ketamine; weak SNDRI action likely contributes to effects and abuse potential

- Ketamine (Ketalar) – anesthetic and dissociative drug of abuse; weak SNDRI action likely contributes to effects and abuse potential

- Phencyclidine (Sernyl) – discontinued anesthetic and dissociative psychostimulant drug of abuse; SNDRI action likely contributes to effects and abuse potential

- Tripelennamine (Pyribenzamine) – antihistamine; weak SNDRI; sometimes abused for this reason

- Mepiprazole

Undergoing Clinical Trials

- Ansofaxine (LY03005/LPM570065). Completed Phase 2 & 3 trials. FDA accepted NDA application.

- Centanafadine (EB-1020) – see here for details 1 to 6 to 14 ratio for NDS. Completed Phase 3 trials for ADHD.

- OPC-64005 – In phase 2 trials (2022)

- Lu AA37096 – see here (SNDRI and 5-HT6 modulator).

- NS-2360 – principle metabolite of tesofensine.

- Tesofensine (NS-2330) (2001) In trials for obesity.

Failed Clinical Trials

- Bicifadine (DOV-220,075) (1981)

- BMS-866,949

- Brasofensine (NS-2214, BMS-204,756) (1995)

- Diclofensine (Ro 8–4650) (1982)

- DOV-216,303 (2004)

- EXP-561 (1965)

- Liafensine (BMS-820,836)

- NS-2359 (GSK-372,475)

- RG-7166 (2009–2012)

- SEP-227,162

- SEP-228,425

- SEP-432 aka SEP-228432, CID:58954867

- Amitifadine (DOV-21,947, EB-1010) (2003)

- Dasotraline (SEP-225,289)

- Lu AA34893 – see here (SNDRI and 5-HT2A, α1, and 5-HT6 modulator)

- Tedatioxetine (Lu AA24530) – SNDRI and 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, 5-HT2A, and α1 modulator

Designer Drugs

- 3-Methyl-PCPy

- Naphyrone (O-2482, naphthylpyrovalerone, NRG-1) (2006)

- 5-APB

Research Compounds (No Record of having been taken by Humans)

- 3,4-Diphenylquinuclidine HCl salt: [72811-36-0].

- 3,4-Diphenylpiperidines (a panoply of analogs was disclosed by French Hoechst) Ref: Patents: The 3′,4′-Dichloro lactam was the most powerful psychostimulant tested. Its SAR can be compared to a similar French Hoechst compound called Lomevactone.

- MDL 47,832 [52423-89-9] Patent: SAR is similar to RG-7166 & Amitifadine. For SAR study see under Osanetant.

- 3,3-Diphenylcyclobutanamine (1978)

- AK Dutta: D-161 (2008) D-473 [1632000-05-5] & D-578.

- DOV-102,677 (2006–2011)

- Fezolamine (Win-41,528-2)

- GlaxoSmithKline (Italia): GSK1360707F (2010): CID:46866510:

- HP-505

- Lundbeck group: Indatraline (1985), Lu-AA42202 & CID:11515108 [874296-10-3].

- JNJ-7925476 (2008; first appeared in 1987), Mcn 5707 [96795-88-9] & Mcn-5292 [105234-89-7].

- Kozikowski group: DMNPC (2000), JZ-IV-10 (2005) & JZAD-IV-22 (2010)

- Lilly group: LR-5182 (maybe only NDRI) (1978) CID:9903806:

- CID:11335177, CID:9867350, CID:11234430

- HM Deutsch group: Methylnaphthidate (HDMP-28) (2001)

- MI-4 MI-4 is the same compound as Ro-25-6981 [169274-78-6]. This is NMDA antagonist.

- Benzazepine derivatives: SKF-83,959 (2013) & Nor-Trepipam [20569-49-7]

- Various phenyltropanes, such as WF-23, dichloropane, and RTI-55

- NeuroSearch group: NS9775, NS18283. & 4-Benzhydryl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine [1186529-81-6].

- CID:54673194 (S/N/D = 0.26/6.0/4.8nM)

- CID:9921901 [387869-25-2], 3-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-tropan-2-ene (S/N/D = 4.7/26/79nM)

- Liming Shao (Sepracor/Sunovion). 3’,4’-Dichlorotramadol, CID:53321058 (S/N/D = 19/04/01nM

- CID:66809062: CID:46870521 CID:10151573 CID:46701015

- Takeda group, CID:44629033 (S/N/D = 11/14/190nM)

- Trudell group: HK3-263 (S/N/D = 0.3/20/16nM)

- Pfizer group CP-607366 & CP-939689.

- Desmethylsertraline – active metabolite of sertraline; 76 nM for SERT, 420 nM for NET, 440 nM for DAT

- 3,4-Dichlorotametraline (trans-(1R,4S)-sertraline) (1980)

- Venlafaxine analogues, LPM580098 & LPM580153. And TP1 later reassigned name to PA01.

- PRC (Carlier) group: PRC200-SS (2008), PRC050, and PRC025.

- Albany Molecular Research group (Bruce Molino) AMR-2 (DAT 3.1nM, SERT 8.3nM, NET 3.0nM)

- CID:49765424 (S)-enantiomer: [1254941-82-6]:

- SK Group: CID:44555333 & CID:49866033

- Boots UK: BTS 74,398, SPD-473 citrate: [161190-26-7]

- Pridefine

- SMe1EC2M3

- SIPI5357 (CID:52939791)

- 23j-S (S/N/D = 83/3.8/160nM)

- Tetrazoles (ROK)

- 10dl (CID:118713802) (S/N/D 7.6/45.2/330nM)

- 2at (CID:118706539)

- THIQ Derivatives: AN12 (CID:10380161): CID:9839278

- 2j (CID:66572162) (S/N/D = 411/71/159nM)

- 6aq (CID:70676472) (S/N/D 44/10/32nM)

- Naphthyl milnacipran analog (2007), CID:17748230 (S/N/D = 18/05/140nM).

Herbals

- The coca flour contains cocaine – natural alkaloid and drug of abuse

- Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) – “The norepinephrine (NET), the serotonin (SERT), the dopamine (DAT) uptake transporters and MAO activity are inhibited by EGb761 in vitro”

- St John’s Wort – natural product and over-the-counter herbal antidepressant

- Hyperforin

- Adhyperforin

- Uliginosin B – IC50 DA = 90 nM, 5-HT = 252 nM, NE = 280 nM

- Oregano extract.

- Although not specifically a SNDRI, Rosmarinus officinalis is one of the trimonoamine modulator (TMM) that affect SER/CAs.

- Hederagenin

Toxicological

Toxicological screening is important to ensure safety of the drug molecules. In this regard, the p m-dichloro phenyl analog of venlafaxine was dropped from further development after its potential mutagenicity was called into question.[158] The mutagenicity of this compound is still doubtful though. It was dropped for other reasons likely related to speed at which it could be released onto the market relative to the more developed compound venlafaxine. More recently, the carcinogenicity of PRC200-SS was likewise reported.

(+)-CPCA (“nocaine”) is the 3R,4S piperidine stereoisomer of (phenyltropane based) RTI-31. It is non addictive, although this might be due to it being a NDRI, not a SNDRI. The β-naphthyl analog of “Nocaine” is a SNDRI though in the case of both the SS and RR enantiomers. Consider the piperidine analogs of brasofensine and tesofensine. These were prepared by NeuroSearch (In Denmark) by the chemists Peter Moldt (2002), and Frank Wätjen (2004–2009). There are four separate isomers to consider (SS, RR, S/R and R/S). This is because there are two chiral carbon sites of asymmetry (means 2 to the power of n isomers to consider where n is the number of chiral carbons). They are therefore a diastereo(iso)meric pair of racemers. With a racemic pair of diastereomers, there is still the question of syn (cis) or anti (trans). In the case of the phenyltropanes, although there are four chiral carbons, there are only eight possible isomers to consider. This is based on the fact that the compound is bicyclic and therefore does not adhere to the equation given above.

It is complicated to explain which isomers are desired. For example, although Alan P. Kozikowski showed that R/S nocaine is less addictive than SS Nocaine, studies on variously substituted phenyltropanes by F. Ivy Carroll et at. revealed that the ββ isomers were less likely to cause convulsions, tremor and death than the corresponding trans isomers (more specifically, what is meant is the 1R,2R,3S isomers). While it does still have to be conceded that RTI-55 caused death at a dosage of 100 mg/kg, it’s therapeutic index of safety is still much better than the corresponding trans isomers because it is more potent compound.

In discussing cocaine and related compounds such as amphetamines, it is clear that these psychostimulants cause increased blood pressure, decreased appetite (and hence weight loss), increased locomotor activity (LMA) etc. In the United States, cocaine overdose is one of the leading causes of ER admissions each year due to drug overdose. People are at increased risk of heart attack and stroke and also present with an array of psychiatric symptoms including anxiety & paranoia etc. On removal of the 2C tropane bridge and on going from RTI-31 to the simpler SS and RS Nocaine it was seen that these compounds still possessed activity as NDRIs but were not powerful psychostimulants. Hence, this might be viewed as a strategy for increasing the safety of the compounds and would also be preferable to use in patients who are not looking to achieve weight loss.

In light of the above paragraph, another way of reducing the psychomotor stimulant and addictive qualities of phenyltropane stimulants is in picking one that is relatively serotonergic. This strategy was employed with success for RTI-112.

Another thing that is important and should be mentioned is the risk for serotonin syndrome when incorporating the element of 5-HT transporter inhibition into a compound that is already fully active as a NDRI (or vice versa). The reasons for serotonin syndrome are complicated and not fully understood.

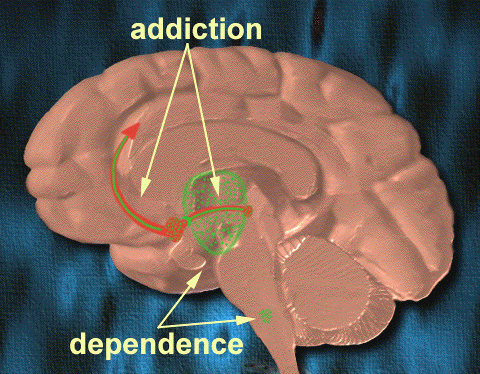

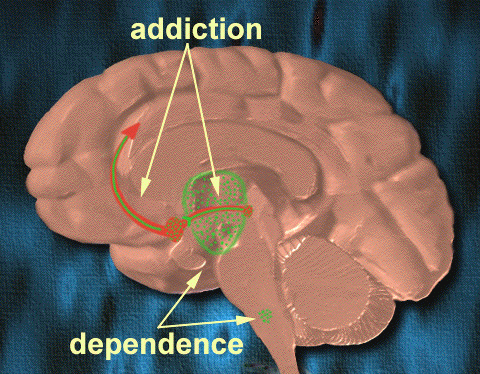

Addiction

Drug addiction may be regarded as a disease of the brain reward system. This system, closely related to the system of emotional arousal, is located predominantly in the limbic structures of the brain. Its existence was proved by demonstration of the “pleasure centres,” that were discovered as the location from which electrical self-stimulation is readily evoked. The main neurotransmitter involved in the reward is dopamine, but other monoamines and acetylcholine may also participate. The anatomical core of the reward system are dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmentum that project to the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, prefrontal cortex and other forebrain structures.

There are several groups of substances that activate the reward system and they may produce addiction, which in humans is a chronic, recurrent disease, characterized by absolute dominance of drug-seeking behaviour.

According to various studies, the relative likelihood of rodents and non-human primates self-administering various psychostimulants that modulate monoaminergic neurotransmission is lessened as the dopaminergic compounds become more serotonergic.

The above finding has been found for amphetamine and some of its variously substituted analogues including PAL-287 etc.

RTI-112 is another good example of the compound becoming less likely to be self-administered by the test subject in the case of a dopaminergic compound that also has a marked affinity for the serotonin transporter.

WIN 35428, RTI-31, RTI-51 and RTI-55 were all compared and it was found that there was a negative correlation between the size of the halogen atom and the rate of self-administration (on moving across the series). Rate of onset was held partly accountable for this, although increasing the potency of the compounds for the serotonin transporter also played a role.

Further evidence that 5-HT dampens the reinforcing actions of dopaminergic medications comes from the co-administration of psychostimulants with SSRIs, and the phen/fen combination was also shown to have limited abuse potential relative to administration of phentermine only.

NET blockade is unlikely to play a major role in mediating addictive behaviour. This finding is based on the premise that desipramine is not self-administered, and also the fact that the NRI atomoxetine was not reinforcing. However, it was still shown to facilitate dopaminergic neurotransmission in certain brain regions such as in the core of the PFC.

Relation to Cocaine

Cocaine is a short-acting SNDRI that also exerts auxiliary pharmacological actions on other receptors. Cocaine is a relatively “balanced” inhibitor, although facilitation of dopaminergic neurotransmission is what has been linked to the reinforcing and addictive effects. In addition, cocaine has some serious limitations in terms of its cardiotoxicity due to its local anaesthetic activity. Thousands of cocaine users are admitted to emergency units in the USA every year because of this; thus, development of safer substitute medications for cocaine abuse could potentially have significant benefits for public health.

Many of the SNDRIs currently being developed have varying degrees of similarity to cocaine in terms of their chemical structure. There has been speculation over whether the new SNDRIs will have an abuse potential like cocaine does. However, for pharmacotherapeutical treatment of cocaine addiction it is advantageous if a substitute medication is at least weakly reinforcing because this can serve to retain addicts in treatment programmes:

… limited reinforcing properties in the context of treatment programs may be advantageous, contributing to improved patient compliance and enhanced medication effectiveness.

However, not all SNDRIs are reliably self-administered by animals. Examples include:

- PRC200-SS was not reliably self-administered.

- RTI-112 was not self-administered because at low doses the compound preferentially occupies the SERT and not the DAT.

- Tesofensine was also not reliably self-administered by human stimulant addicts.

- The nocaine analogue JZAD-IV-22 only partly substituted for cocaine in animals, but produced none of the psychomotor activation of cocaine, which is a trait marker for stimulant addiction.

Legality

Cocaine is a controlled drug (Class A in the UK; Schedule II in the USA); it has not been entirely outlawed in most countries, as despite having some “abuse potential” it is recognised that it does have medical uses.

Brasofensine was made “class A” in the UK under the MDA (misuse of drugs act). The semi-synthetic procedure for making BF uses cocaine as the starting material.

Naphyrone first appeared in 2006 as one of quite a large number of analogues of pyrovalerone designed by the well-known medicinal chemist P. Meltzer et al. When the designer drugs mephedrone and methylone became banned in the United Kingdom, vendors of these chemicals needed to find a suitable replacement. Mephedrone and methylone affect the same chemicals in the brain as a SNDRI, although they are thought to act as monoamine releasers and not act through the reuptake inhibitor mechanism of activity. A short time later, mephedrone and methylone were banned (which had become quite popular by the time they became illegal), naphyrone appeared under the trade name NRG-1. NRG-1 was promptly illegalised, although it is not known if its use resulted in any hospitalisations or deaths.

Role of Monoamine Neurotransmitters

Monoamine Hypothesis

The original monoamine hypothesis postulates that depression is caused by a deficiency or imbalances in the monoamine neurotransmitters (5-HT, NE, and DA). This has been the central topic of depression research for approximately the last 50 years; it has since evolved into the notion that depression arises through alterations in target neurons (specifically, the dendrites) in monoamine pathways.

When reserpine (an alkaloid with uses in the treatment of hypertension and psychosis) was first introduced to the West from India in 1953, the drug was unexpectedly shown to produce depression-like symptoms. Further testing was able to reveal that reserpine causes a depletion of monoamine concentrations in the brain. Reserpine’s effect on monoamine concentrations results from blockade of the vesicular monoamine transporter, leading to their increased catabolism by monoamine oxidase. However, not everyone has been convinced by claims that reserpine is depressogenic, some authors (David Healy in particular) have even claimed that it is antidepressant.

Tetrabenazine, a similar agent to reserpine, which also depletes catecholamine stores, and to a lesser degree 5-HT, was shown to induce depression in many patients.

Iproniazid, an inhibitor of MAO, was noted to elevate mood in depressed patients in the early 1950s, and soon thereafter was shown to lead to an increase in NA and 5-HT.

Hertting et al. demonstrated that the first TCA, imipramine, inhibited cellular uptake of NA in peripheral tissues. Moreover, both antidepressant agents were demonstrated to prevent reserpine-induced sedation. Likewise, administration of DOPA to laboratory animals was shown to reverse reserpine induced sedation; a finding reproduced in humans. Amphetamine, which releases NA from vesicles and prevents re-uptake was also used in the treatment of depression at the time with varying success.

In 1965 Schildkraut formulated the catecholamine theory of depression. This was subsequently the most widely cited article in the American Journal of Psychiatry. The theory stated that “some, if not all, depressions are associated with an absolute or relative deficiency of catecholamines, in particular noradrenaline (NA), at functionally important adrenergic receptor sites in the brain. However, elation may be associated with an excess of such amines.”

Shortly after Schildkraut’s catecholamine hypothesis was published, Coppen proposed that 5-HT, rather than NA, was the more important neurotransmitter in depression. This was based on similar evidence to that which produced the NA theory as reserpine, imipramine, and iproniazid affect the 5-HT system, in addition to the noradrenergic system. It was also supported by work demonstrating that if catecholamine levels were depleted by up to 20% but 5-HT neurotransmission remained unaltered there was no sedation in animals. Alongside this, the main observation promoting the 5-HT theory was that administration of a MAOI in conjunction with tryptophan (precursor of 5-HT) elevated mood in control patients and potentiated the antidepressant effect of MAOI. Set against this, combination of an MAOI with DOPA did not produce a therapeutic benefit.

Inserting a chlorine atom into imipramine leads to clomipramine, a drug that is much more SERT selective than the parent compound.

Clomipramine was a predecessor to the development of the more recent SSRIs. There was, in fact, a time prior to the SSRIs when selective NRIs were being considered (c.f. talopram and melitracen). In fact, it is also believed that the selective NRI nisoxetine was discovered prior to the invention of fluoxetine. However, the selective NRIs did not get promoted in the same way as did the SSRIs, possibly due to an increased risk of suicide. This was accounted for on the basis of the energising effect that these agents have. Moreover, NRIs have the additional adverse safety risk of hypertension that is not seen for SSRIs. Nevertheless, NRIs have still found uses.

Further support for the monoamine hypothesis came from monoamine depletion studies:

- Alpha-methyl-p-tyrosine (AMPT) is a tyrosine hydroxylase enzyme inhibitor that serves to inhibit catecholamine synthesis. AMPT led to a resurgence of depressive symptoms in patients improved by the NE reuptake inhibitor (NRI) desipramine, but not by the SSRI fluoxetine. The mood changes induced by AMPT may be mediated by decreases in norepinephrine, while changes in selective attention and motivation may be mediated by dopamine.

- Dietary depletion of the DA precursors phenylalanine and tyrosine does not result in the relapse of formerly depressed patients off their medication.

- Administration of fenclonine (para-chlorophenylalanine) is able to bring about a depletion of 5-HT. The mechanism of action for this is via tryptophan hydroxylase inhibition. In the 1970s administration of parachlorophenylalanine produced a relapse in depressive symptoms of treated patients, but it is considered too toxic for use today.

- Although depletion of tryptophan — the rate-limiting factor of serotonin synthesis — does not influence the mood of healthy volunteers and untreated patients with depression, it does produce a rapid relapse of depressive symptoms in about 50% of remitted patients who are being, or have recently been treated with serotonin selective antidepressants.

Dopaminergic

There appears to be a pattern of symptoms that are currently inadequately addressed by serotonergic antidepressants – loss of pleasure (anhedonia), reduced motivation, loss of interest, fatigue and loss of energy, motor retardation, apathy and hypersomnia. Addition of a pro-dopaminergic component into a serotonin based therapy would be expected to address some of these short-comings.

Several lines of evidence suggest that an attenuated function of the dopaminergic system may play an important role in depression:

- Mood disorders are highly prevalent in pathologies characterized by a deficit in central DA transmission such as Parkinson’s disease (PD). The prevalence of depression can reach up to 50% of individuals with PD.

- Patients taking strong dopaminergic antagonists such as those used in the treatment of psychosis are more likely than the general population to develop symptoms of depression.

- Data from clinical studies have shown that DA agonists, such as bromocriptine, pramipexole and ropinirole, exhibit antidepressant properties.

- Amineptine, a TCA-derivative that predominantly inhibits DA re-uptake and has minimal noradrenergic and serotonergic activity has also been shown to possess antidepressant activity. A number of studies have suggested that amineptine has similar efficacy to the TCAs, MAOIs and SSRIs. However, amineptine is no longer available as a treatment for depression due to reports of an abuse potential.

- The B-subtype selective MAOI selegiline (a drug developed for the treatment of PD) has now been approved for the treatment of depression in the form of a transdermal patch (Emsam). For some reason, there have been numerous reports of users taking this drug in conjunction with β-phenethylamine.

- Taking psychostimulants for the alleviation of depression is well proven strategy, although in a clinical setting the use of such drugs is usually prohibited because of their strong addiction propensity.

- When users withdraw from psychostimulant drugs of abuse (in particular, amphetamine), they experience symptoms of depression. This is likely because the brain enters into a hypodopaminergic state, although there might be a role for noradrenaline also.

For these drugs to be reinforcing, they must block more than 50% of the DAT within a relatively short time period (<15 minutes from administration) and clear the brain rapidly to enable fast repeated administration.

In addition to mood, they may also improve cognitive performance, although this remains to be demonstrated in humans.

The rate of clearance from the body is faster for ritalin than it is for regular amphetamine.

Noradrenergic

The decreased levels of NA proposed by Schildkraut, suggested that there would be a compensatory upregulation of β-adrenoceptors. Despite inconsistent findings supporting this, more consistent evidence demonstrates that chronic treatment with antidepressants and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) decrease β-adrenoceptor density in the rat forebrain. This led to the theory that β-adrenoceptor downregulation was required for clinical antidepressant efficacy. However, some of the newly developed antidepressants do not alter, or even increase β-adrenoceptor density.

Another adrenoceptor implicated in depression is the presynaptic α2-adrenoceptor. Chronic desipramine treatment in rats decreased the sensitivity of α2-adrenoceptors, a finding supported by the fact that clonidine administration caused a significant increase in growth hormone (an indirect measure of α2-adrenoceptor activity) although platelet studies proved inconsistent. This supersensitivity of α2-adrenoceptor was postulated to decrease locus coeruleus (the main projection site of NA in the central nervous system, CNS) NA activity leading to depression.

In addition to enhancing NA release, α2-adrenoceptor antagonism also increases serotonergic neurotransmission due to blockade of α2-adrenoceptors present on 5-HT nerve terminals.

Serotonergic

5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT or serotonin) is an important cell-to-cell signalling molecule found in all animal phyla. In mammals, substantial concentrations of 5-HT are present in the central and peripheral nervous systems, gastrointestinal tract and cardiovascular system. 5-HT is capable of exerting a wide variety of biological effects by interacting with specific membrane-bound receptors, and at least 13 distinct 5-HT receptor subtypes have been cloned and characterised. With the exception of the 5-HT3 receptor subtype, which is a transmitter-gated ion channel, 5-HT receptors are members of the 7-transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. In humans, the serotonergic system is implicated in various physiological processes such as sleep-wake cycles, maintenance of mood, control of food intake and regulation of blood pressure. In accordance with this, drugs that affect 5-HT-containing cells or 5-HT receptors are effective treatments for numerous indications, including depression, anxiety, obesity, nausea, and migraine.

Because serotonin and the related hormone melatonin are involved in promoting sleep, they counterbalance the wake-promoting action of increased catecholaminergic neurotransmission. This is accounted for by the lethargic feel that some SSRIs can produce, although TCAs and antipsychotics can also cause lethargy albeit through different mechanisms.

Appetite suppression is related to 5-HT2C receptor activation as for example was reported for PAL-287 recently.

Activation of the 5-HT2C receptor has been described as “panicogen” by users of ligands for this receptor (e.g., mCPP). Antagonism of the 5-HT2C receptor is known to augment dopaminergic output. Although SSRIs with 5-HT2C antagonist actions were recommended for the treatment of depression, 5-HT2C receptor agonists were suggested for treating cocaine addiction since this would be anti-addictive. Nevertheless, the 5-HT2C is known to be rapidly downregulated upon repeated administration of an agonist agent, and is actually antagonized.

Azapirone-type drugs (e.g. buspirone), which act as 5-HT1A receptor agonists and partial agonists have been developed as anxiolytic agents that are not associated with the dependence and side-effect profile of the benzodiazepines. The hippocampal neurogenesis produced by various types of antidepressants, likewise, is thought to be mediated by 5-HT1A receptors. Systemic administration of a 5-HT1A agonist also induces growth hormone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release through actions in the hypothalamus.

Current Antidepressants

Most antidepressants on the market today target the monoaminergic system.

SSRIs

The most commonly prescribed class of antidepressants in the USA today are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These drugs inhibit the uptake of the neurotransmitter 5-HT by blocking the SERT, thus increasing its synaptic concentration, and have shown to be efficacious in the treatment of depression, however sexual dysfunction and weight gain are two very common side-effects that result in discontinuation of treatment.

Although many patients benefit from SSRIs, it is estimated that approximately 50% of depressive individuals do not respond adequately to these agents. Even in remitters, a relapse is often observed following drug discontinuation. The major limitation of SSRIs concerns their delay of action. It appears that the clinical efficacy of SSRIs becomes evident only after a few weeks.

SSRIs can be combined with a host of other drugs including bupropion, α2 adrenergic antagonists (e.g. yohimbine) as well as some of the atypical antipsychotics. The augmentation agents are said to behave synergistically with the SSRI although these are clearly of less value than taking a single compound that contains all of the necessary pharmacophoric elements relative to the consumption of a mixture of different compounds. It is not entirely known what the reason for this is, although ease of dosing is likely to be a considerable factor. In addition, single compounds are more likely to be approved by the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration) than are drugs that contain greater than one pharmaceutical ingredient (polytherapies).

A number of SRIs were under development that had auxiliary interactions with other receptors. Particularly notable were agents behaving as co-joint SSRIs with additional antagonist activity at 5-HT1A receptors. 5-HT1A receptors are located presynaptically as well as post-synaptically. It is the presynaptic receptors that are believed to function as autoreceptors (cf. studies done with pindolol). These agents were shown to elicit a more robust augmentation in the % elevation of extracellular 5-HT relative to baseline than was the case for SSRIs as measured by in vivo microdialysis.

NRIs

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) such as reboxetine prevent the reuptake of norepinephrine, providing a different mechanism of action to treat depression. However reboxetine is no more effective than the SSRIs in treating depression. In addition, atomoxetine has found use in the treatment of ADHD as a non-addictive alternative to Ritalin. The chemical structure of atomoxetine is closely related to that of fluoxetine (an SSRI) and also duloxetine (SNRI).

NDRIs

Bupropion is a commonly prescribed antidepressant that acts as a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI). It prevents the reuptake of NA and DA (weakly) by blocking the corresponding transporters, leading to increased noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission. This drug does not cause sexual dysfunction or weight gain like the SSRIs but has a higher incidence of nausea. Methylphenidate is a much more reliable example of an NDRI (the action that it displays on the DAT usually getting preferential treatment). Methylphenidate is used in the treatment of ADHD; its use in treating depression is not known to have been reported, but it is presumed owing to its psychomotor activating effects and it functioning as a positive reinforcer. There are also reports of methylphenidate being used in the treatment of psychostimulant addiction, in particular cocaine addiction, since the addictive actions of this drug are believed to be mediated by the dopamine neurotransmitter.

SNRIs

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine (Effexor), its active metabolite desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), and duloxetine (Cymbalta) prevent the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine, however their efficacy appears to be only marginally greater than the SSRIs.

Sibutramine is the name of an SNRI based appetite suppressant with use in the treatment of obesity. This was explored in the treatment of depression, but was shown not to be effective.

Both sibutramine and venlafaxine are phenethylamine-based. At high doses, both venlafaxine and sibutramine will start producing dopaminergic effects. The inhibition of DA reuptake is unlikely to be relevant at clinically approved doses.

MAOIs

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were the first antidepressants to be introduced. They were discovered entirely by serendipity. Iproniazide (the first MAOI) was originally developed as an antitubercular agent but was then unexpectedly found to display antidepressant activity.

Isoniazid also displayed activity as an antidepressant, even though it is not a MAOI. This led some people to question whether it is some property of the hydrazine, which is responsible for mediating the antidepressant effect, even going as far as to state that the MAOI activity could be a secondary side-effect. However, with the discovery of tranylcypromine (the first non-hydrazine MAOI), it was shown that MAOI is thought to underlie the antidepressant bioactivity of these agents. Etryptamine is another example of a non-hydrazine MAOI that was introduced.

The MAOIs work by inhibiting the monoamine oxidase enzymes that, as the name suggests, break down the monoamine neurotransmitters. This leads to increased concentrations of most of the monoamine neurotransmitters in the human brain, serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine and melatonin. The fact that they are more efficacious than the newer generation antidepressants is what leads scientists to develop newer antidepressants that target a greater range of neurotransmitters. The problem with MAOIs is that they have many potentially dangerous side-effects such as hypotension, and there is a risk of food and drug interactions that can result in potentially fatal serotonin syndrome or a hypertensive crisis. Although selective MAOIs can reduce, if not eliminate these risks, their efficacy tends to be lower.

MAOIs may preferentially treat TCA-resistant depression, especially in patients with features such as fatigue, volition inhibition, motor retardation and hypersomnia. This may be a function of the ability of MAOIs to increase synaptic levels of DA in addition to 5-HT and NE. The MAOIs also seem to be effective in the treatment of fatigue associated with fibromyalgia (FM) or chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS).

Although a substantial number of MAOIs were approved in the 1960s, many of these were taken off the market as rapidly as they were introduced. The reason for this is that they were hepatotoxic and could cause jaundice.

TCAs

The first tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), imipramine (Tofranil), was derived from the antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine, which was developed as a useful antihistaminergic agent with possible use as a hypnotic sedative. Imipramine is an iminodibenzyl (dibenzazepine).

The TCAs such as imipramine and amitriptyline typically prevent the reuptake of serotonin or norepinephine.

It is the histaminiergic (H1), muscarinic acetylcholinergic (M1), and alpha adrenergic (α1) blockade that is responsible for the side-effects of TCAs. These include somnolence and lethargy, anticholinergic side-effects, and hypotension. Due to the narrow gap between their ability to block the biogenic amine uptake pumps versus the inhibition of fast sodium channels, even a modest overdose of one of the TCAs could be lethal. TCAs were, for 25 years, the leading cause of death from overdoses in many countries. Patients being treated with antidepressants are prone to attempt suicide and one method they use is to take an overdose of their medications.

Another example of a TCA is amineptine which is the only one believed to function as a DRI. It is no longer available.

Failure of SNDRIs for Depression

SNDRIs have been under investigation for the treatment of major depressive disorder for a number of years but, as of 2015, have failed to meet effectiveness expectations in clinical trials. In addition, the augmentation of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with lisdexamfetamine, a norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent, recently failed to separate from placebo in phase III clinical trials of individuals with treatment-resistant depression, and clinical development was subsequently discontinued. These occurrences have shed doubt on the potential benefit of dopaminergic augmentation of conventional serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressant therapy. As such, scepticism has been cast on the promise of the remaining SNDRIs that are still being trialled, such as ansofaxine (currently in phase II trials), in the treatment of depression. Nefazodone a weak SNDRI has been successful in treating major depressive disorder which makes it unique.

This page is based on the copyrighted Wikipedia article < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine_reuptake_inhibitor >; it is used under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA). You may redistribute it, verbatim or modified, providing that you comply with the terms of the CC-BY-SA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.