Introduction

Inoculation theory is a social psychological/communication theory that explains how an attitude or belief can be made resistant to persuasion or influence, in analogy to how a body gains resistance to disease. The theory uses medical inoculation as its explanatory analogy but instead of applying it to disease, it is used to discuss attitudes and other positions, like opinions, values, and beliefs. It has applicability to public campaigns targeting misinformation and fake news, but it is not limited to misinformation and fake news.

The theory was developed by social psychologist William J. McGuire in 1961 to explain how attitudes and beliefs change, and more specifically, how to keep existing attitudes and beliefs consistent in the face of attempts to change them. Inoculation theory functions to confer resistance of counter-attitudinal influences from such sources as the media, advertising, interpersonal communication, and peer pressure.

The theory posits that weak counterarguments generate resistance within the receiver, enabling them to maintain their beliefs in the face of a future, stronger challenge. Following exposure to weak counterarguments (e.g. counterarguments that have been paired with refutations), the receiver will then seek out supporting information to further strengthen their threatened position. The held attitude or belief becomes resistant to a stronger “attack,” hence the medical analogy of a vaccine.

Inoculating messages can raise and refute the same counterarguments in the “attack” (refutational same) or different counterarguments on the same or a related issue (refutational different). The effect of the inoculating message can be amplified by making the message of vested and immediate importance to the receiver (based on Jack Brehm’s psychological reactance theory). Post-inoculation talk can further spread inoculation effects to their social network, and the act of talking to others can additionally strengthen resistance to attitude change.

Therapeutic inoculation is a recent extension in which an inoculation message is presented to those without the targeted belief or attitude in place. Applied in this way, an inoculation message can both change an existing position and make that new position more resistant to future attacks.

Brief History

William McGuire set out to conduct research on ways to encourage opposition to persuasion while others created experiments to do the opposite. McGuire was motivated to study inoculation and persuasion as a result of the aftermath of the Korean War. McGuire was concerned for those who were forced into certain situations which was the main inspiration for this theory. Nine US prisoners of war, when given the opportunity, elected to remain with their captors. Many assumed they were brainwashed, so McGuire and other social scientists turned to ways of conferring resistance to persuasion. This was a change in extant persuasion research, which was almost exclusively concerned with how to make messages more persuasive, and not the other way around.

The theory of inoculation was derived from previous research studying one-sided and two-sided messages. One-sided messages are supportive messages to strengthen existing attitudes, but with no mention of counter-positions. One-sided messages are frequently seen in political campaigns when a candidate denigrates his or her opponent through “mudslinging”. This method is effective in reinforcing extant attitudes of derision toward the opposition and support for the “mudslinging” candidate. If the audience supports the opposition, however, the attack message is ineffective. Two-sided messages present both counterarguments and refutations of those counterarguments. To gain compliance and source credibility, a two-sided message must demonstrate the sender’s position, then the opposition’s position, followed by a refutation of the opposition’s argument, then finally the sender’s position again.

McGuire led a series of experiments assessing inoculation’s efficacy and adding nuance to our understanding for how it works). Early studies limited testing of inoculation theory to cultural truisms, or beliefs accepted without consideration (e.g. people should brush their teeth daily). This meant it was primarily used toward the attitudes that were rarely, if ever attacked by opposing forces. The early tests of inoculation theory were used on non-controversial issues, (e.g. brushing your teeth is good for you). Few refute that brushing one’s teeth is a good habit, therefore external opposing arguments against tooth brushing would not change one’s opinion, but it would strengthen support for brushing one’s teeth. Studies of inoculation theory currently target less popular or common attitudes, such as whether one should buy a Mac or a Windows-based PC computer or if one should support gay marriage.

Implementing inoculation theory in studies of contemporary social issues (from mundane to controversial social issues), and the variety and resurgence of such studies, helps bolster the effectiveness and utility of the theory and provides support that it can be used to strengthen and/or predict attitudes. These later developments of the theory extended inoculation to more controversial and contested topics in the contexts of politics, health, marketing, and contexts in which people have different pre-existing attitudes, such as climate change. The theory has also been applied in education to help prevent substance abuse.

About

Inoculation is a theory that explains how attitudes and beliefs can be made more resistant to future challenges. For an inoculation message to be successful, the recipient experiences threat (a recognition that a held attitude or belief is vulnerable to change) and is exposed to and/or engages in refutational processes (pre-emptive refutation, that is, defences against potential counterarguments). The arguments that are presented in an inoculation message must be strong enough to initiate motivation to maintain current attitudes and beliefs, but weak enough that the receiver will be able to refute the counterargument.

Inoculation theory has been studied and tested through decades of scholarship, including experimental laboratory research and field studies. Inoculation theory is used today as part of the suite of tools by those engaged in shaping or manipulating public opinion. These contexts include: politics, health campaigns marketing, education, and science communication, among others.

The inoculation process is analogous to the medical inoculation process from which it draws its name; the analogy served as the inaugural exemplar for how inoculation confers resistance. As McGuire (1961) initially explained, medical inoculation works by exposing the body to a weakened form of a virus – strong enough to trigger a response (that is, the production of antibodies), but not so strong as to overwhelm the body’s resistance. Attitudinal inoculation works the same way: expose the receiver to weakened counterarguments, triggering refutational processes (like counterarguing) which confers resistance to later, stronger “attack” like persuasive messages. This process works like a metaphorical vaccination: the receiver becomes immune to attacking messages that attempt to change their attitudes or beliefs. Inoculation theory suggests that if one sends out messages with weak counterarguments, an individual can build immunity to stronger messages and strengthen their original attitudes toward an issue.

Most inoculation theory research treats inoculation as a pre-emptive, preventive (prophylactic) messaging strategy—used before exposure to strong challenges. More recently, scholars have begun to test inoculation as a therapeutic inoculation treatment, administered to those who have the “wrong” target attitude/belief. In this application, the treatment messages both persuade and inoculate—much like a flu shot that cures those who already have been infected with the flu and protects them against future threats. More research is needed to better understand therapeutic inoculation treatments – especially field research that takes inoculation outside of the laboratory setting.

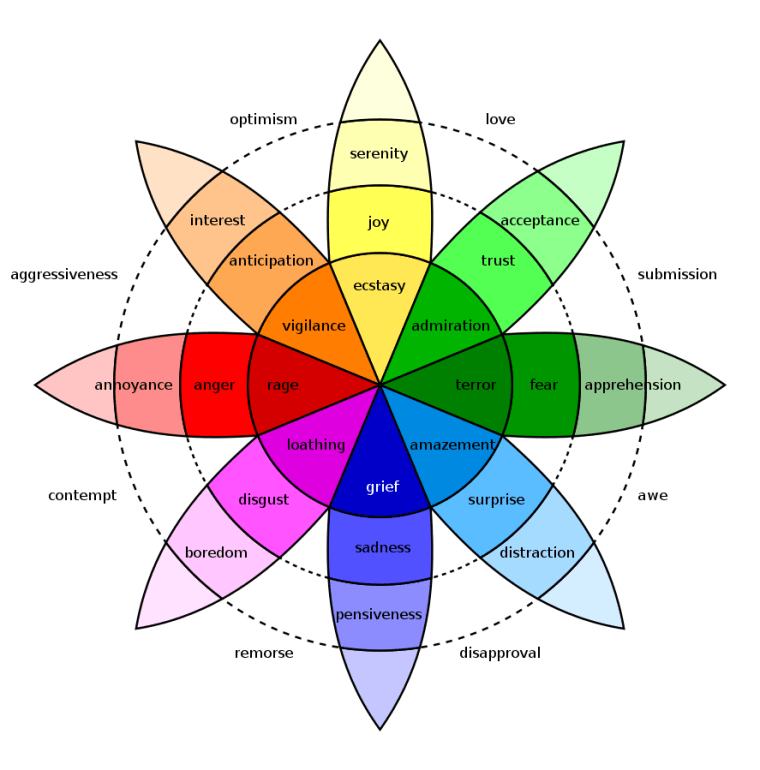

Another shift in inoculation research moves from a largely cognitive, intrapersonal (internal) process to a process that is both cognitive and affective, intrapersonal and interpersonal. For example, in contrast to explanations of inoculation that focused nearly entirely on cognitive processes (like internal counterarguing, or refuting persuasive attempts silently, in one’s own mind), more recent research has examined how inoculation messages motivate actual talk (conversation, dialogue) about the target issue. Scholars have confirmed that exposure to an inoculation message motivates more post-inoculation talk (PIT) about the issue. For example, Tweets containing native advertising disclosures – a type of inoculation message – were more likely to include negative commentary which is a sign of resistance to influence consistent with PIT.

Pre-Bunking

It is much more difficult to eliminate the influence or persuasion of misinformation once individuals have seen it which is why debunking and fact checking have failed in the past. Due to this, a phenomenon known as pre-bunking as introduced. Pre-bunking (or prebunking) is a form of Inoculation theory that aims to combat various kinds of manipulation and misinformation spread around the web. In recent years, misleading information and the permeation of such have become an increasingly prevalent issue. Standard Inoculation theory aims to combat persuasion. Still pre-bunking seeks to target misinformation by providing a harmless example of it. Exposure builds future resistance to similar misinformation.

In 2021, Nanlan Zhang examined inoculation by looking at harsh, preconceived ideas of mental health. Such ideas included the association of mental health with violence. The study consisted of two different experiments, including 593 participants. In the first, subjects were shown misinformation regarding gun violence, only to have the misinformation explained away. These inoculative techniques were concluded to be slightly effective. In the second experiment of the study, subjects were shown false messages that had either high or low credibility. In the first half of the study, the inoculation affected > 50% of the participants. The second half of the study showed increased effectiveness in inoculation, with subjects showing distrust in high and low credibility messages.

A common form of pre-bunking is in the form of short videos, meant to grab a viewer’s attention with a fake message and then inoculate the viewer by explaining the manipulation. In 2022, Jon Roozenbeek (with funding from Google) developed five pre-bunking video to test the viability of short-form inoculation messages. A total of 29,116 subjects were then shown multiple fabricated posts from various social media outlets. The subjects were then tasked with differentiating between benign posts and ones containing manipulation. The videos were effective in improving the viewer’s ability to identify manipulative tactics. Viewers showed about a 5% average increase in identifying such tactics.

Explanation

Inoculation theory explains how attitudes, beliefs, or opinions (sometimes referred to generically as “a position”) can be made more resistant to future challenges. Receivers are made aware of the potential vulnerability of an existing position (e.g. attitude, belief). This establishes threat and initiates defences to future attacks. The idea is that when a weak argument is presented in the inoculation message, processes of refutation or other means of protection will prepare for use of stronger arguments later. It is critical that the attack is strong enough to keep the receiver defensive, but weak enough to not actually change those pre-existing ideas. This will hopefully make the receiver actively defensive and allow them to create arguments in favour of their pre-existing thoughts. The more active receivers become in their defence the more it will strengthen their own attitudes, beliefs, or opinions.

Key Components

There are at least four basic key components to successful inoculation: threat, refutational pre-emption (pre-emptive refutation), delay, and involvement.

- Threat. Threat provides motivation to protect one’s attitudes or beliefs. Threat is a product of the presence of counterarguments in an inoculation message and/or an explicit forewarning of an impending challenge to an existing belief. The message receiver must interpret that a message is threatening and recognise that there is a reason to fight to maintain and strengthen their opinion. If the receiver of an opposing message does not recognize that a threat is present, they will not feel the need to start defending their position and therefore will not change their attitude or strengthen their opinion. Compton and Ivanov (2012) found that participants who had been forewarned of an attack–i.e. threat–but not given the appropriate tools to combat the attack were more resistant than the control group. In this case, the simple act of forewarning of an attack was enough to resist the counter-attitudinal persuasion.

- Refutational pre-emption. This component is the cognitive part of the process. It is the ability to activate one’s own argument for future defence and strengthen their existing attitudes through counterarguing. Scholars have also explored whether other resistance processes might be at work, including affect. Refutational preemption provides specific content that receivers can employ to strengthen attitudes against subsequent change. This aids in the inoculation process by giving the message receiver a chance to argue with the opposing message. It shows the message receiver that their attitude is not the only attitude or even the right attitude, creating a threat to their beliefs. This is beneficial because the receiver will get practice in defending their original attitude, therefore strengthening it. This is important in fighting off future threats of opposing messages and helps to ensure that the message will not affect their original stance on the issues. Refutational preemption acts as the weak strain of the virus in the metaphor. By injecting the weakened virus–the opposing opinion–into a receiver, this prompts the receiver to strengthen their position, enabling them to fight off the opposing threat. By the time the body processes the virus–the counterattack–the receiver will have learned how to eliminate the threat. In the case of messaging, if the threatening message is weak or unconvincing, a person can reject the message and stick with their original stance on the matter. By being able to reject threatening messages a person builds strength of their belief and every successful threatening message that they can encounter their original opinions only get stronger. Recent research has studied the presence and function of word-of-mouth communication, or post-inoculation talk, following exposure to inoculation messages.

- Delay. There has been much debate on whether there is a certain amount of time necessary between inoculation and further attacks on a person’s attitude that will be most effective in strengthening that person’s attitude. McGuire (1961) suggested that delay was necessary to strengthen a person’s attitude and since then many scholars have found evidence to back that idea up. There are also scholars on the other side who suggest that too much of a delay lessens the strengthening effect of inoculation. Nevertheless, the effect of inoculation can still be significant weeks or even months after initial introduction or the treatment showing that it does produce somewhat long-lasting effects. Despite the limited research in this area, meta-analysis suggests that the effect becomes weakened after too long of a delay, specifically after 13 days.

- Involvement. Involvement, which is one of the most important concepts for widespread persuasion, can be defined as how important the attitude object is for the receiver (Pfau, et al. (1997)). Involvement is critical because it determines how effective the inoculation process will be, if at all. If an individual does not have a vested interest in the subject, they will not perceive a threat and, consequently, will not feel the need to defend and strengthen their original opinion, rendering the inoculation process ineffective.

Refutational Same and Different Messages

While there are many studies that have been conducted comparing different treatments of inoculation, there is one specific comparison that is mentioned throughout various studies. This is the comparison between what is known as refutational same and refutational different messages. A refutational same message is an inoculation treatment that refutes specific potential counterarguments that will appear in the subsequent persuasion message, while refutational different treatments are refutations that are not the same as those present in the impending persuasive message. Pfau and his colleagues (1990) developed a study during the 1988 United States presidential election. The Republicans were claiming that the Democratic candidate was known to be lenient when it came to the issue of crime. The researchers developed a refutational same message that stated that while the Democratic candidate was in favour of tough sentences, merely tough sentences could not reduce crime. The refutational different message expanded on the candidate’s platform and his immediate goals if he were to be elected. The study showed comparable results between the two different treatments. Importantly, as McGuire and others had found previously, inoculation was able to confer resistance to arguments that were not specifically mentioned in the inoculation message.

Psychological Reactance

Recent inoculation studies have incorporated Jack Brehm’s psychological reactance theory, a theory of freedom and control. The purpose is to enhance or boost resistance outcomes for the two key components of McGuire’s inoculation theory: threat and refutational pre-emption.

Such a study is the large complex multisite study of Miller et al. (2013). The main focus is to determine how to improve the effectiveness of the inoculation process by evaluating and generating reactance to a threatened freedom by manipulating explicit and implicit language and its intensity. While most inoculation studies focus on avoiding reactance, or at the very least, minimizing the impact of reactance on behaviours, in contrast, Miller, et al. chose to manipulate reactance by designing messages to enhance resistance and counterarguing output. They showed that inoculation coupled with reactance-enhanced messages leads to “stronger resistance effects”. Most importantly, reactance-enhanced inoculations result in lesser attitude change—the ultimate measure of resistance.

The participants in the Miller et al. study were college students, that is emerging adults, who display high reactance to persuasive appeals. This population is in a transitional uncertain stage in life, and are more likely to defend their behavioural freedoms if they feel others are attempting to control their behaviour. Populations in transitional stages rely on source credibility as a major proponent of cognitive processing and message acceptance. If the message is explicit and threatens their perceived freedoms, such populations will most likely derogate (criticise) the source and dismiss the message. Two important needs for reactance to a threatened freedom from an emerging adult population are immediacy and vested interest Miller et al. discuss how emerging adults need to believe their behavioural freedoms, for which they have vestedness, are being threatened, and that the threat exists in real time with almost immediate consequences. Threats that their perceived freedoms will be eliminated or minimised increases motivation to restore that freedom, or possibly engage in the threatened behaviour to reinforce their autonomy and control of their attitudes and actions. In addition, that threat does not necessarily need anger to motivate counter-argumentation, and simply attempting to provoke anger through manipulation is limited as a technique of gauging negative cognitions. Miller et al. also consider refutational pre-emption as motivation for producing initial counterarguments and provocation of dissension when contemplating the attack message.

A unique feature of their study is examining low-controlling versus high-controlling language and its impact on affect and source credibility. They found reactance enhances key resistance outcomes, including: threat, anger at attack message source, negative cognitions, negative affect, anticipated threat to freedom, anticipated attack message source derogation, perceived threat to freedom, perceived attack message source derogation, and counterarguing.

Previously, Miller, et al. (2007) utilises Brehm’s psychological reactance theory[27] to avoid or eliminate source derogation and message rejection. In this study, their focus is instead Brehm’s concept of restoration. Some of their ideas deal with low reactance and whether it can lead to more positive outcomes and if behavioural freedoms can be restored once threatened. As discussed in Miller, et al. (2013), this study ponders whether individuals know they have the behavioural freedom that is being threatened and whether they feel they are worthy of that freedom. This idea also ties into the emerging adult population of the above study and its affirmation that individuals in transitional stages will assert their threatened behaviour freedoms.

Miller et al. (2007) sought to determine how effective explicit and implicit language is at mitigating reactance. Particularly, restoration of freedom is a focus of this study, and gauging how concrete and abstract language informs an individual’s belief that he or she has a choice. Some participants were given a persuasive appeal related to health promotion with a following post-scripted message designed to remind them they have a choice as a method of restoring the participants’ freedom. Using concrete language proved more effective at increasing the possibilities of message acceptance and source credibility. This study is relevant to inoculation research in that it lends credence to Miller, et al. (2013), which transparently incorporates psychological reactance theory in conjunction with inoculation theory to improve the quality of persuasive appeals in the future.

Postinoculation Talk

Following Compton and Pfau’s (2009) research on postinoculation talk, Ivanov, et al. (2012) explore how cognitive processing could lead to talk with others after receiving an inoculation message in which threat exists. The authors found that message processing leads to postinoculation talk which could potentially lead to stronger resistance to attack messages. Further, postinoculation talk acts virally, spreading inoculation through talk with others on issues that involve negative cognitions and affect. In previous research, the assumption that talk was subvocal (existing only intrapersonally) was prevalent, without concern for the impact of vocal talk with other individuals. The authors deem vocal talk important to the incubation process. Their study concluded that individuals who receive an inoculation message that contains threat will talk to others about the message and talk more frequently than individuals who do not receive an inoculation message. Additionally, the act of postinoculation talk bolsters their attitudes and increases resistance to the message as well as increasing the likelihood that talk will generate a potentially viral effect–spreading inoculation to others through the act of vocal talk.

Straw man Fallacy

Due to the nature of attitudinal inoculation as a form of psychological manipulation, the counterarguments used in the process do not necessarily need to be accurately representative of the opposing belief in order to trigger the inoculation effect. This is a form of straw man fallacy, and can be effectively used to reinforce beliefs with less legitimate support.

Real-World Applications

Most research has involved inoculation as applied to interpersonal communication (persuasion), marketing, health and political messaging. More recently, inoculation strategies are starting to show potential as a counter to science denialism and cyber security breaches.

Science Denialism

Science denialism has rapidly increased in recent years. A major factor is the rapid spread of misinformation and fake news via social media (such as Facebook), as well as prominent placing of such misinformation in Google searches. Climate change denialism is a particular problem in that its global nature and lengthy timeframe is uniquely difficult for the individual mind to grasp, as the human brain has evolved to deal with short-term and immediate dangers. However, John Cook and colleagues have shown that inoculation theory shows promise in countering denialism. This involves a two-step process. Firstly, list and deconstruct the 50 or so most common myths about climate change, by identifying the reasoning errors and logical fallacies of each one. Secondly, use the concept of parallel argumentation to explain the flaw in the argument by transplanting the same logic into a parallel situation, often an extreme or absurd one. Adding appropriate humour can be particularly effective.

Cyber Security

Treglia and Delia (2017) apply inoculation theory to cyber security (internet security, cybercrime). People are susceptible to electronic or physical tricks, scams, or misrepresentations that may lead to deviating from security procedures and practices, opening the operator, organisation, or system to exploits, malware, theft of data, or disruption of systems and services. Inoculation in this area improves peoples resistance to such attacks. Psychological manipulation of people into performing actions or divulging confidential information via the internet and social media is one part of the broader construct of social engineering.

Political Campaigning

Compton and Ivanov (2013) offer a comprehensive review of political inoculation scholarship and outline new directions for future work.

In 1990, Pfau and his colleagues examined inoculation through the use of direct mail during the 1988 United States presidential campaign. The researchers were specifically interested in comparing inoculation and post hoc refutation. Post hoc refutation is another form of building resistance to arguments; however, instead of building resistance prior to future arguments, like inoculation, it attempts to restore original beliefs and attitudes after the counterarguments have been made. Results of the research reinforced prior conclusions that refutational same and different treatments both increase resistance to attacks. More importantly, results also indicated inoculation was superior to post hoc refutation when attempting to protect original beliefs and attitudes.

Other examples are studies showing it is possible to inoculate political supporters of a candidate in a campaign against the influence of an opponent’s attack adverts; and inoculate citizens of fledgling democracies against the spiral of silence (fear of isolation) which can thwart the expression of minority views.

Health

Much of the research conducted in health is attempting to create campaigns that will encourage people to stop unhealthy behaviours (e.g. getting people to stop smoking or prevention of teen alcoholism). Compton, Jackson and Dimmock (2016) reviewed studies where inoculation theory was applied to health-related messaging. There are many inoculation studies with the intent to inoculate children and teenagers to prevent them from smoking, doing drugs or drinking alcohol. Much of the research shows that targeting at a young age can help them resist peer pressure in high school or college. An important example of inoculation theory usage is protecting young adolescents against influences of peer pressure, which can lead to smoking, underage drinking, and other harmful behaviours.

Godbold and Pfau (2000) used sixth graders from two different schools and applied inoculation theory as a defence against peer pressure to drinking alcohol. They hypothesized that a normative message (a message tailored around the current social norms) would be more effective than an informative message. An informative message is a message tailored around giving individuals information pieces. In this case, the information was why drinking alcohol is bad. The second hypothesis was that subjects who receive a threat two weeks later will be more resistant than those receiving an immediate attack. The results supported the first hypothesis partially. The normative message created higher resistance from the attack, but was not necessarily more effective. The second hypothesis was also not supported; therefore, the time lapse did not create further resistance for teenagers against drinking. One major outcome from this study was the resistance created by utilizing a normative message.

In another study conducted by Duryea (1983), the results were far more supportive of the theory. The study also attempted to find the message to use for educational training to help prevent teen drinking and driving. The teen subjects were given resources to combat attempts to persuade them to drink and drive or to get into a vehicle with a drunk driver. The subjects were:

- Shown a film;

- Participated in question and answer;

- Role playing exercises; and

- A slide show.

The results showed that a combination of the four methods of training was effective in combating persuasion to drink and drive or get into a vehicle with a drunk driver. The trained group was far more prepared to combat the persuasive arguments.

Additionally, Parker, Ivanov, and Compton (2012) found that inoculation messages can be an effective deterrent against pressures to engage in unprotected sex and binge drinking—even when only one of these issues is mentioned in the health message.

Compton, Jackson and Dimmock (2016) discuss important future research, such as preparing new mothers for overcoming their health concerns (e.g. about breastfeeding, sleep deprivation and post-partum depression).

Inoculation theory applied to prevention of smoking has been heavily studied. These studies have mainly focused on preventing youth smokers–inoculation seems to be most effective in young children. For example, Pfau, et al. (1992) examined the role of inoculation when attempting to prevent adolescents from smoking. One of the main goals of the study was to examine longevity and persistence of inoculation. Elementary school students watched a video warning them of future pressures to smoke. In the first year, resistance was highest among those with low self-esteem. At the end of the second year, students in the group showed more attitudinal resistance to smoking than they did previously (Pfau & Van Bockern 1994). Importantly, the study and its follow-up demonstrate the long-lasting effects of inoculation treatments.

Grover (2011) researched the effectiveness of the “truth” anti-smoking campaign on smokers and non-smokers. The truth adverts aimed to show young people that smoking was unhealthy, and to expose the manipulative tactics of tobacco companies. Grover showed that inoculation works differently for smokers and non-smokers (i.e. potential smokers). For both groups, the truth adverts increased anti-smoking and anti-tobacco-industry attitudes, but the effect was greater for smokers. The strength of this attitude change is partly mediated (controlled) by aversion to branded tobacco industry products. However, counter-intuitively, exposure to pro-smoking adverts increased aversion to branded tobacco industry products (at least in this sample). In general, Grover demonstrated that the initial attitude plays a major role in the ability to inoculate an individual.

Future health-related studies can be extremely beneficial to communities. Some research areas include present-day issues (for example, inoculation-based strategies for addiction intervention to assist sober individuals from relapsing), as well as promoting healthy eating habits, exercising, breastfeeding and creating positive attitude towards mammograms. An area that has been underdeveloped is mental health awareness. Because of the large number of young adults and teens dying of suicide due to bullying, inoculation messages could be effective.

Dimmock et al. (2016) studied how inoculation messages can be used to increase participants’ reported enjoyment and interest in physical exercise. In this study, participants are exposed to inoculating messages and then given an intentionally boring exercise routine. These messages cause the reinforcement of the individual’s positive attitude towards the exercise, and as a result increase their likelihood to continue exercise in the future.

Vaccination Beliefs

Inoculation Theory has been used to combat misinformation regarding vaccine related beliefs. Vaccinations have helped stop the spread of many infections and diseases, but their effectiveness has become a controversial topic in the Western nations. Studies show that misinformation regarding the science has played a major role in the hesitancy for vaccinations. Some of the common misconceptions include the Influenza vaccine giving the flu and a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Regardless of the many scientific studies debunking these claims, there are people that still cling to these beliefs.

In 2016, a study was conducted to see Inoculation theory combat vaccine misinformation. The participants of this study were a group of 110 young women who had not completed any doses of the human Papillomavirus vaccine (HPV). The study wanted to see the effect of attack messages that questioned the importance and safety of this specific vaccine, and other vaccines. After making arguments against the vaccines and a brief lapse in time, a control group was exposed to inoculation messages, that were in favour of the vaccine. Once the arguments were made, the participants were asked to take part in post-test measurements. The results found that those who received the inoculated messages had more positive behaviours towards the HPV vaccine, and other vaccines.

In 2017, a study was conducted to test Inoculation theory’s role in making vaccine related decisions. A group of 89 British parents were selected, and exposed to one of five potential arguments for a fictitious vaccine. Some groups were exposed to arguments that were completely based in conspiracy, Anti-conspiracy, While the other groups were exposed to both arguments in differing order. After being exposed to these arguments, they were told about a disease that would cause vomiting and a severe fever. The parents were asked if they would get their children the vaccine for this fictitious disease, and the results they gathered displayed Inoculation theory in action. The results showed that those who were exposed to anti-conspiracy arguments were more likely to get the vaccine.

Marketing

It took some time for inoculation theory to be applied to marketing, because of many possible limitations. Lessne and Didow (1987) reviewed publications about inoculation application to marketing campaigns and their limitations. They note that, at the time, the closest to true marketing context was Hunt’s 1973 study on the Chevron campaign. The Federal Trade Commission stated that Chevron had deceived consumers on the effectiveness of their gas additive F-310. The FTC was going to conduct a corrective advertising campaign to disclose the information. In response, Chevron ran a print campaign to combat the anticipated FTC campaign. The double page advertisement read, “If every motorist used Chevron with F-310 for 2000 miles, air pollutants would be reduced by thousands of tons in a single day. The FTC doesn’t think that’s significant.” Hunt used this real-life message as an inoculation treatment in his research. He used the corrective campaign by the FTC as the attack on the positive attitude toward Chevron. The results indicated that a supportive treatment offered less resistance than a refutational treatment. Another finding was that when an inoculative treatment is received, but no attack is followed, there is a drop in attitude. One of the major limitations in this study was that Hunt did not allow a time elapse between the treatment and the attack, which was a major element of McGuire’s original theory.

Inoculation theory can be used with an audience who already has an opinion on a brand, to convince existing customers to continue patronage of a company, or to protect commercial brands against the influence of comparative adverts from a competitor. An example is Apple Computers’ “Get A Mac” campaign. This campaign follows inoculation theory in targeting those who already preferred Mac computers. The series of ads put out in the duration of the campaign had a similar theme; they directly compared Macs and PCs. Inoculation theory applies here as these commercials are likely aimed at Apple users. These ads are effective because Apple users already prefer Mac computers, and they are unlikely to change their minds. This comparison creates refutational pre-emption, showing Macs may not be the only viable options on the market. The TV ads throw in a few of the positive advantages that PCs have over Macs, but by the end of every commercial they reiterate the fact that Macs are ultimately the superior consumer product. This reassures viewers that their opinion is still right and that Macs are in fact better than PCs. The inoculation theory in these ads keep Mac users coming back for Apple products, and may even have them coming back sooner for the new bigger and better products that Apple releases – especially important as technology is continually changing, and something new is always being pushed onto the shelves.

Inoculation theory research in advertising and marketing has mainly focused on promoting healthy lifestyles with the help of a product or for a specific company’s goal. However, shortly after McGuire published his inoculation theory, Szybillo and Heslin (1973) applied the concepts that McGuire used in the health industry to advertising and marketing campaigns. They sought to provide answers for advertisers marketing a controversial product or topic: if an advertiser knew the product or campaign would cause an attack, what would be the best advertising strategy? Would they want to refute the arguments or reaffirm their claims? They chose a then-controversial topic: “Inflatable air bags should be installed as passive safety devices in all new cars.” They tested four advertising strategies:

- Defence;

- Refutational-same;

- Refutational-different; and

- Supportive.

The results confirmed that a reaffirmation or refutation approach is better than not addressing the attack. They also confirmed that refuting the counterargument is more effective than a supportive defence (though the refutational-different effect was not much greater than for supportive defence). Szybillo and Heslin also manipulated the time of the counterargument attack, and the credibility of the source, but neither was significant.

In 2006, a jury awarded Martin Dunson and Lisa Jones, the parents of one-year-old Marquis Matthew Dunson, $5 million for the death of their son. Dunson and Jones sued Johnson & Johnson, the makers of Infant’s Tylenol claiming that there were not enough warnings regarding the dosage of acetaminophen What resulted was a Johnson & Johnson campaign that encouraged parents to practice proper dosage procedures. In a review of the campaign by Veil and Kent (2008), they breakdown the message of the campaign utilizing the basic concepts of inoculation theory. They theorise that Johnson & Johnson used inoculation to alter the negative perception of their product. The campaign began running prior to the actual verdict, thus the timing seemed suspicious. A primary contention of Veil and Kent was that the intentions of Johnson & Johnson were not to convey consumer safety guidelines, but to change how consumers might respond to further lawsuits on overdose. The inoculation strategy used by Johnson & Johnson is evident in their campaign script: “Some people think if you have a really bad headache, you should take extra medicine.” The term “some people” is referring to the party suing the company. The commercial also used the Vice President of Sales for Tylenol to deliver a message, who may be considered a credible source.

In 1995, Burgoon and colleagues published empirical findings on issue/advocacy advertising campaigns. Most, if not all, of these types of advertising campaigns utilize inoculation to create the messages. They posited that inoculation strategies should be used for these campaigns to enhance the credibility of the corporation, and to aid in maintain existing consumer attitudes (but not to change consumer attitudes). Based on the analysis of previous research they concluded issue/advocacy advertising is most effective for reinforcing support and avoid potential slippage in the attitudes of supporters. They used Mobil Oil’s issue/advocacy campaign message. They found that issue/advocacy adverts did work to inoculate against counter-attitudinal attacks. They also found that issue/advocacy adverts work to protect the source credibility. The results also indicated that political views play a role in the effectiveness of the campaigns. Thus, conservatives are easier to inoculate than moderates or liberals. They also concluded that females are more likely to be inoculated with these types of campaigns. An additional observation was that the type of content used in these campaigns contributed to the campaigns success. The further the advertisement was from “direct self-benefit” the greater the inoculation effect was on the audience.

Compton and Pfau (2004) extended inoculation theory into the realm of credit card marketing targeting college students. They wondered if inoculation could help protect college students against dangerous levels of credit card debt and/or help convince them to increase their efforts to pay down any existing debt. Inoculation seemed to reinforce students’ wanted attitudes to debt, as well as some of their behavioural intentions. Further, they found some evidence that those who received the inoculation treatment were more likely to talk to their friends and family about issues of credit card debt.

Deception

Inoculation theory plays a role in deception detection research. Deception detection research has largely yielded little predictable support for nonverbal cues, and rather indicates that most liars are revealed through verbal content inconsistencies. These inconsistencies can be revealed through a form of inoculation theory that exposes the subject to a distorted version of the suspected action to observe inconsistencies in their responses.

Journalism

Breen and Matusitz (2009) suggest a method through which inoculation theory can be used to prevent pack journalism, a practice in which a large quantity of journalists and news outlets swarm a person, place, thing, or idea in a way that is distressing and harmful. It also lends itself to plagiarism. Through this framework derived from Pfau and Dillard (2000), journalists are inoculated against news practices of other journalists and instead directed towards uniqueness and originality, thus avoiding pack journalism.

This page is based on the copyrighted Wikipedia article < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inoculation_theory >; it is used under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA). You may redistribute it, verbatim or modified, providing that you comply with the terms of the CC-BY-SA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.