Introduction

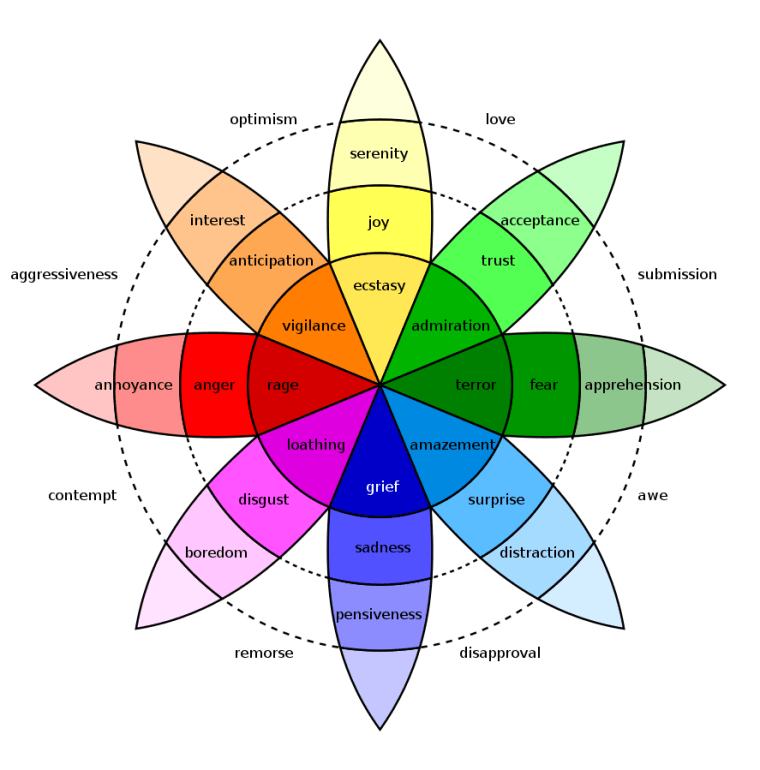

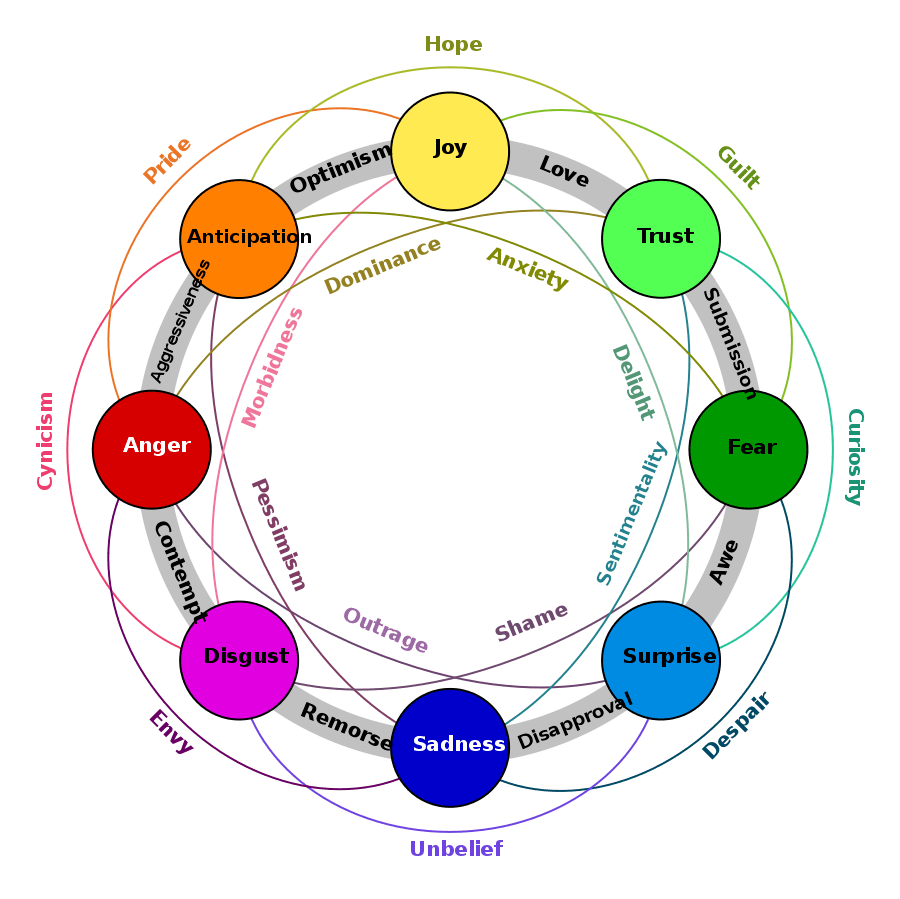

Motivated reasoning (motivational reasoning bias) is a cognitive and social response in which individuals, consciously or sub-consciously, allow emotion-loaded motivational biases to affect how new information is perceived. Individuals tend to favour evidence that coincides with their current beliefs and reject new information that contradicts them, despite contrary evidence.

Motivated reasoning overlaps with confirmation bias. Both favour evidence supporting one’s beliefs, at the same time dismissing contradictory evidence. However, confirmation bias is mainly a sub-conscious (innate) cognitive bias. In contrast, motivated reasoning (motivational bias) is a sub-conscious or conscious process by which one’s emotions control the evidence supported or dismissed. For confirmation bias, the evidence or arguments can be logical as well as emotional.

Motivated reasoning can be classified into two categories:

- Accuracy-oriented (non-directional), in which the motive is to arrive at an accurate conclusion, irrespective of the individual’s beliefs; and

- Goal-oriented (directional), in which the motive is to arrive at a particular conclusion.

Refer to Motivated Forgetting, Emotional Reasoning, and Motivated Tactician.

Definitions

Motivated reasoning is a cognitive and social response, in which individuals, consciously or unconsciously, allow emotion-loaded motivational biases to affect how new information is perceived. Individuals tend to favour arguments that support their current beliefs and reject new information that contradicts these beliefs.

Motivated reasoning, confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance are closely related. Both motivated reasoning and confirmation bias favour evidence supporting one’s beliefs, at the same time dismissing contradictory evidence. Motivated reasoning (motivational bias) is an unconscious or conscious process by which personal emotions control the evidence that is supported or dismissed. However, confirmation bias is mainly an unconscious (innate, implicit) cognitive bias, and the evidence or arguments utilised can be logical as well as emotional. More broadly, it is feasible that motivated reasoning can moderate cognitive biases generally, including confirmation bias.

Individual differences such as political beliefs can moderate the emotional/motivational effect. In addition, social context (groupthink, peer pressure) also partly controls the evidence utilised for motivated reasoning, particularly in dysfunctional societies. Social context moderates emotions, which in turn moderate beliefs.

Motivated reasoning differs from critical thinking, in which beliefs are assessed with a sceptical but open-minded attitude.

Cognitive Dissonance

Individuals are compelled to initiate motivated reasoning to lessen the amount of cognitive dissonance they feel. Cognitive dissonance is the feeling of psychological and physiological stress and unease between two conflicting cognitive and/or emotional elements (such as the desire to smoke, despite knowing it is unhealthy). According to Leon Festinger, there are two paths individuals can engage in to reduce the amount of distress: the first is altering behaviour or cognitive bias; the second, more common path is avoiding or discrediting information or situations that would create dissonance.

Research suggests that reasoning away contradictions is psychologically easier than revising feelings. Emotions tend to colour how “facts” are perceived. Feelings come first, and evidence is used in service of those feelings. Evidence that supports what is already believed is accepted; evidence which contradicts those beliefs is not.

Mechanisms: Cold and Hot Cognition

The notion that motives or goals affect reasoning has a long and controversial history in social psychology. This is because supportive research could be reinterpreted in entirely cognitive non-motivational terms (the hot versus cold cognition controversy). This controversy existed because of a failure to explore mechanisms underlying motivated reasoning.

Early research on how humans evaluated and integrated information supported a cognitive approach consistent with Bayesian probability, in which individuals weighted new information using rational calculations (“cold cognition”). More recent theories endorse these cognitive processes as only partial explanations of motivated reasoning, but have also introduced motivational[1] or affective (emotional) processes (“hot cognition”).

Kunda Theory

Ziva Kunda reviewed research and developed a theoretical model to explain the mechanism by which motivated reasoning results in bias. Motivation to arrive at a desired conclusion provides a level of arousal, which acts as an initial trigger for the operation of cognitive processes. To participate in motivated reasoning, either consciously or subconsciously, an individual first needs to be motivated. Motivation then affects reasoning by influencing the knowledge structures (beliefs, memories, information) that are accessed and the cognitive processes used.

Lodge–Taber Theory

Milton Lodge and Charles Taber introduced an empirically supported model in which affect is intricately tied to cognition, and information processing is biased toward support for positions that the individual already holds. Their model has three components:

- On-line processing, in which, when called on to make an evaluation, people instantly draw on stored information which is marked with affect;

- A component by which affect is automatically activated along with the cognitive node to which it is tied; and

- An “heuristic mechanism” for evaluating new information, which triggers a reflection on “How do I feel?” about this topic. This process results in a bias towards maintaining existing affect, even in the face of other, disconfirming information.

This theory is developed and evaluated in their book The Rationalizing Voter (2013). David Redlawsk (2002) found that the timing of when disconfirming information was introduced played a role in determining bias. When subjects encounter incongruity during an information search, the automatic assimilation and update process is interrupted. This results in one of two outcomes:

- Subjects may enhance attitude strength in a desire to support existing affect (resulting in degradation in decision quality and potential bias); or

- Subjects may counter-argue existing beliefs in an attempt to integrate the new data.

This second outcome is consistent with research on how processing occurs when one is tasked with accuracy goals.

To summarise, the two models differ in that Kunda identifies a primary role for cognitive strategies such as memory processes, and the use of rules in determining biased information selection, whereas Lodge and Taber identify a primary role for affect in guiding cognitive processes and maintaining bias.

Neuroscientific Evidence

A neuroimaging study by Drew Westen and colleagues does not support the use of cognitive processes in motivated reasoning, lending greater support to affective processing as a key mechanism in supporting bias. This study, designed to test the neural circuitry of individuals engaged in motivated reasoning, found that motivated reasoning “was not associated with neural activity in regions previously linked with cold reasoning tasks [Bayesian reasoning] nor conscious (explicit) emotion regulation”.

This neuroscience data suggests that “motivated reasoning is qualitatively distinct from reasoning when people do not have a strong emotional stake in the conclusions reached.” However, if there is a strong emotion attached during their previous round of motivated reasoning and that emotion is again present when the individual’s conclusion is reached, a strong emotional stake is then attached to the conclusion. Any new information in regards to that conclusion will cause motivated reasoning to reoccur. This can create pathways within the neural network that further ingrain the reasoned beliefs of that individual along similar neural networks to where logical reasoning occurs. This causes the strong emotion to reoccur when confronted with contradictory information, time and time again. This is referred to by Lodge and Taber as affective contagion. But instead of “infecting” other individuals, the emotion “infects” the individual’s reasoning pathways and conclusions.

Categories

Motivated reasoning can be classified into two categories:

- Accuracy-oriented (non-directional), in which the motive is to arrive at an accurate conclusion, irrespective of the individual’s beliefs; and

- Goal-oriented (directional), in which the motive is to arrive at a particular conclusion.

Politically motivated reasoning, in particular, is strongly directional.

Despite their differences in information processing, an accuracy-motivated and a goal-motivated individual can reach the same conclusion. Both accuracy-oriented and directional-oriented messages move in the desired direction. However, the distinction lies in crafting effective communication, where those who are accuracy motivated will respond better to credible evidence catered to the community, while those who are goal-oriented will feel less threatened when the issue is framed to fit their identity or values.

Accuracy-Oriented (Non-Directional) Motivated Reasoning

Several works on accuracy-driven reasoning suggest that when people are motivated to be accurate, they expend more cognitive effort, attend to relevant information more carefully, and process it more deeply, often using more complex rules.

Kunda asserts that accuracy goals delay the process of coming to a premature conclusion, in that accuracy goals increase both the quantity and quality of processing—particularly in leading to more complex inferential cognitive processing procedures. When researchers manipulated test subjects’ motivation to be accurate by informing them that the target task was highly important or that they would be expected to defend their judgments, it was found that subjects utilized deeper processing and that there was less biasing of information. This was true when accuracy motives were present at the initial processing and encoding of information. In reviewing a line of research on accuracy goals and bias, Kunda concludes, “several different kinds of biases have been shown to weaken in the presence of accuracy goals”. However, accuracy goals do not always eliminate biases and improve reasoning: some biases (e.g. those resulting from using the availability heuristic) might be resistant to accuracy manipulations. For accuracy to reduce bias, the following conditions must be present:

- Subjects must possess appropriate reasoning strategies.

- They must view these as superior to other strategies.

- They must be capable of using these strategies at will.

However, these last two conditions introduce the construct that accuracy goals include a conscious process of utilising cognitive strategies in motivated reasoning. This construct is called into question by neuroscience research that concludes that motivated reasoning is qualitatively distinct from reasoning in which there is no strong emotional stake in the outcomes. Accuracy-oriented individuals who are thought to use “objective” processing can vary in information updating, depending on how much faith they place in a provided piece of evidence and inability to detect misinformation that can lead to beliefs that diverge from scientific consensus.

Goal-Oriented (Directional) Motivated Reasoning

Directional goals enhance the accessibility of knowledge structures (memories, beliefs, information) that are consistent with desired conclusions. According to Kunda, such goals can lead to biased memory search and belief construction mechanisms. Several studies support the effect of directional goals in selection and construction of beliefs about oneself, other people and the world.

Cognitive dissonance research provides extensive evidence that people may bias their self-characterisations when motivated to do so. Other biases such as confirmation bias, prior attitude effect and disconfirmation bias could contribute to goal-oriented motivated reasoning. For example, in one study, subjects altered their self-view by viewing themselves as more extroverted when induced to believe that extroversion was beneficial.

Michael Thaler of Princeton University, conducted a study that found that men are more likely than women to demonstrate performance-motivated reasoning due to a gender gap in beliefs about personal performance. After a second study was conducted the conclusion was drawn that both men and women are susceptible to motivated reasoning, but certain motivated beliefs can be separated into genders.

The motivation to achieve directional goals could also influence which rules (procedural structures, such as inferential rules) are accessed to guide the search for information. Studies also suggest that evaluation of scientific evidence may be biased by whether the conclusions are in line with the reader’s beliefs.

In spite of goal-oriented motivated reasoning, people are not at liberty to conclude whatever they want merely because of that want. People tend to draw conclusions only if they can muster up supportive evidence. They search memory for those beliefs and rules that could support their desired conclusion or they could create new beliefs to logically support their desired goals.

Case Studies

Smoking

When an individual is trying to quit smoking, they might engage in motivated reasoning to convince themselves to keep smoking. They might focus on information that makes smoking seem less harmful while discrediting any evidence which emphasizes any dangers associated with the behaviour. Individuals in situations like this are driven to initiate motivated reasoning to lessen the amount of cognitive dissonance they feel. This can make it harder for individuals to quit and lead to continued smoking, even though they know it is not good for their health.

Political Bias

Peter Ditto and his students conducted a meta-analysis in 2018 of studies relating to political bias. Their aim was to assess which US political orientation (left/liberal or right/conservative) was more biased and initiated more motivated reasoning. They found that both political orientations are susceptible to bias to the same extent. The analysis was disputed by Jonathan Baron and John Jost, to whom Ditto and colleagues responded. Reviewing the debate, Stuart Vyse concluded that the answer to the question of whether US liberals or conservatives are more biased is: “We don’t know.”

On 22 April 2011, The New York Times published a series of articles attempting to explain the Barack Obama citizenship conspiracy theories. One of these articles by political scientist David Redlawsk explained these “birther” conspiracies as an example of political motivated reasoning. US presidential candidates are required to be born in the US. Despite ample evidence that President Barack Obama was born in the US state of Hawaii, many people continue to believe that he was not born in the US, and therefore that he was an illegitimate president. Similarly, many people believe he is a Muslim (as was his father), despite ample lifetime evidence of his Christian beliefs and practice (as was true of his mother). Subsequent research by others suggested that political partisan identity was more important for motivating “birther” beliefs than for some other conspiracy beliefs such as 9/11 conspiracy theories.

Climate Change

Despite a scientific consensus on climate change, citizens are divided on the topic, particularly along political lines. A significant segment of the American public has fixed beliefs, either because they are not politically engaged, or because they hold strong beliefs that are unlikely to change. Liberals and progressives generally believe, based on extensive evidence, that human activity is the main driver of climate change. By contrast, conservatives are generally much less likely to hold this belief, and a subset believes that there is no human involvement, and that the reported evidence is faulty (or even fraudulent). A prominent explanation is political directional motivated reasoning, in that conservatives are more likely to reject new evidence that contradicts their long established beliefs. In addition, some highly directional climate deniers not only discredit scientific information on human-induced climate change but also to seek contrary evidence that leads to a posterior belief of greater denial.

A study by Robin Bayes and colleagues of the human-induced climate change views of 1,960 members of the Republican Party found that both accuracy and directional motives move in the desired direction, but only in the presence of politically motivated messages congruent with the induced beliefs.

Social Media

Social media is used for many different purposes and ways of spreading opinions. It is the number one place people go to get information and most of that information is complete opinion and bias. The way this applies to motivated reasoning is the way it spreads. “However, motivated reasoning suggests that informational uses of social media are conditioned by various social and cultural ways of thinking”. All ideas and opinions are shared and makes it very easy for motivated reasoning and biases to come through when searching for an answer or just facts on the internet or any news source.

COVID-19

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, people who refuse to wear masks or get vaccinated may engage in motivated reasoning to justify their beliefs and actions. They may reject scientific evidence that supports mask-wearing and vaccination and instead seek out information that supports their pre-existing beliefs, such as conspiracy theories or misinformation. This can lead to behaviours that are harmful to both themselves and others.

In a 2020 study, Van Bavel and colleagues explored the concept of motivated reasoning as a contributor to the spread of misinformation and resistance to public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their results indicated that people often engage in motivated reasoning when processing information about the pandemic, interpreting it to confirm their pre-existing beliefs and values. The authors argue that addressing motivated reasoning is critical to promoting effective public health messaging and reducing the spread of misinformation. They suggested several strategies, such as reframing public health messages to align with individuals’ values and beliefs. In addition, they suggested using trusted sources to convey information by creating social norms that support public health behaviours.

Outcomes and Tackling Strategies

The outcomes of motivated reasoning derive from “a biased set of cognitive processes—that is, strategies for accessing, constructing, and evaluating beliefs. The motivation to be accurate enhances use of those beliefs and strategies that are considered most appropriate, whereas the motivation to arrive at particular conclusions enhances use of those that are considered most likely to yield the desired conclusion.” Careful or “reflective” reasoning has been linked to both overcoming and reinforcing motivated reasoning, suggesting that reflection is not a panacea, but a tool that can be used for rational or irrational purposes depending on other factors. For example, when people are presented with and forced to think analytically about something complex that they lack adequate knowledge of (i.e. being presented with a new study on meteorology whilst having no degree in the subject), there is no directional shift in thinking, and their extant conclusions are more likely to be supported with motivated reasoning. Conversely, if they are presented with a more simplistic test of analytical thinking that confronts their beliefs (i.e. seeing implausible headlines as false), motivated reasoning is less likely to occur and a directional shift in thinking may result.

Hostile Media Effect

Research on motivated reasoning tested accuracy goals (i.e. reaching correct conclusions) and directional goals (i.e. reaching preferred conclusions). Factors such as these affect perceptions; and results confirm that motivated reasoning affects decision-making and estimates. These results have far reaching consequences because, when confronted with a small amount of information contrary to an established belief, an individual is motivated to reason away the new information, contributing to a hostile media effect. If this pattern continues over an extended period of time, the individual becomes more entrenched in their beliefs.

Tipping Point

However, recent studies have shown that motivated reasoning can be overcome. “When the amount of incongruency is relatively small, the heightened negative affect does not necessarily override the motivation to maintain [belief].” However, there is evidence of a theoretical “tipping point” where the amount of incongruent information that is received by the motivated reasoner can turn certainty into anxiety. This anxiety of being incorrect may lead to a change of opinion to the better.

This page is based on the copyrighted Wikipedia article < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motivated_reasoning >; it is used under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA). You may redistribute it, verbatim or modified, providing that you comply with the terms of the CC-BY-SA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.