Introduction

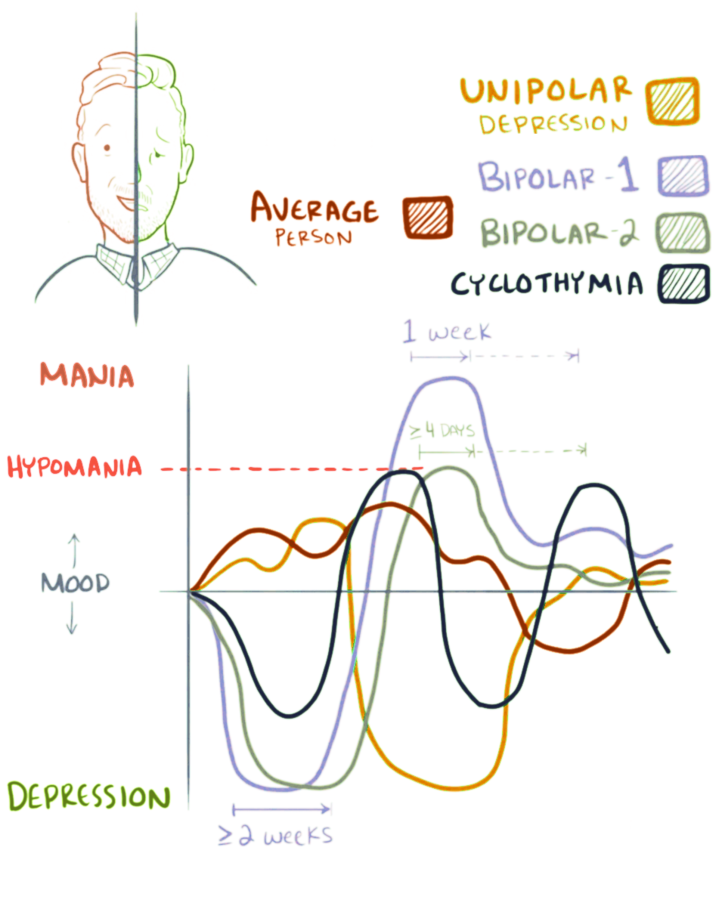

Bipolar disorder is an affective disorder characterised by periods of elevated and depressed mood.

The cause and mechanism of bipolar disorder is not yet known, and the study of its biological origins is ongoing. Although no single gene causes the disorder, a number of genes are linked to increase risk of the disorder, and various gene environment interactions may play a role in predisposing individuals to developing bipolar disorder. Neuroimaging and post-mortem studies have found abnormalities in a variety of brain regions, and most commonly implicated regions include the ventral prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Dysfunction in emotional circuits located in these regions have been hypothesized as a mechanism for bipolar disorder. A number of lines of evidence suggests abnormalities in neurotransmission, intracellular signalling, and cellular functioning as possibly playing a role in bipolar disorder.

Studies of bipolar disorder, particularly neuroimaging studies, are vulnerable to the confounding effects such as medication, comorbidity, and small sample size, leading to underpowered independent studies, and significant heterogeneity.

Aetiology

Genetic

The etiology of bipolar disorder is unknown. The overall heritability of bipolar is estimated at 79%-93%, and first degree relatives of bipolar probands have a relative risk of developing bipolar around 7-10. While the heritability is high, no specific genes have been conclusively associated with bipolar, and a number of hypothesis have been posited to explain this fact. “The polygenic common rare variant” hypothesis suggests that a large number of risk conferring genes are carried in a population, and that a disease manifests when a person has a sufficient number of these genes. The “multiple rare variant” model suggests that multiple genes that are rare in the population are capable of causing a disease, and that carrying one or a few can lead to disease. The familial transmission of mania and depression are largely independent of each other. This raises the possibility that bipolar is actually two biologically distinct but highly comorbid conditions.

A number of genome wide associations have been reported, including CACNA1C and ODZ4, and TRANK1. Less consistently reported loci include ANK3 and NCAN, ITIH1, ITIH3 and NEK4. Significant overlaps with schizophrenia have been reported at CACNA1C, ITIH, ANK3, and ZNF804A. This overlap is congruent with the observation that relatives of probands with schizophrenia are at higher risk for bipolar disorder and vice versa.

In light of associations between bipolar and circadian abnormalities (such as decreased need for sleep and increased sleep latency), polymorphisms in the CLOCK gene have been tested for association, although findings have been inconsistent, and one meta analysis has reported no association with either bipolar or major depressive disorder. Other circadian genes associated with bipolar at relaxed significance thresholds include ARTNL, RORB, and DEC1. One meta analysis reported a significant association of the short allele of the serotonin transporter, although the study was specific to European populations. Two polymorphisms in the tryptophan hydroxylase 2 gene have been associated with bipolar disorder. NFIA has been linked with seasonal patterns of mania.

One particular SNP located on CACNA1C that confers risk for bipolar disorder is also associated with elevated CACNA1C mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex, and increased calcium channel expression in neurons made from patient induced pluripotent stem cells.

No significant association exists for the BDNF Val66Met allele and bipolar disorder, except possibly in a subgroup of bipolar II cases, and suicide.

Due to the inconsistent findings in GWAS, multiple studies have undertaken the approach of analysing SNPs in biological pathways. Signalling pathways traditionally associated with bipolar disorder that have been supported by these studies include CRH signalling, cardiac β-adrenergic signalling, phospholipase C signalling, glutamate receptor signalling, cardiac hypertrophy signalling, Wnt signalling, notch signalling, and endothelin 1 signalling. Of the 16 genes identified in these pathways, three were found to be dysregulated in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex portion of the brain in post-mortem studies, CACNA1C, GNG2, and ITPR2.

Advanced paternal age has been linked to a somewhat increased chance of bipolar disorder in offspring, consistent with a hypothesis of increased new genetic mutations.

A meta-analysis was performed to determine the association between bipolar disorder and oxidative DNA damage measured by 8-hydroxy-2′-8-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) or 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG). Levels of 8-OHdG and 8-oxodG are widely used as measures of oxidative stress in mental illnesses. It was determined from this meta-analysis that oxidative DNA damage was significantly increased in bipolar disorder.

Environmental

Manic episodes can be produced by sleep deprivation in around 30% of people with bipolar. While not all people with bipolar demonstrate seasonality of affective symptoms, it is a consistently reported feature that supports theories of circadian dysfunction in bipolar.

Risk factors for bipolar include obstetric complications, abuse, drug use, and major life stressors.

The “kindling model” of mood disorders suggests that major environmental stressors trigger initial mood episodes, but as mood episodes occur, weaker and weaker triggers can precipitate an affective episode. This model was initially created for epilepsy, to explain why weaker and weaker electrical stimulation was necessary to elicit a seizure as the disease progressed. While parallels have been drawn between bipolar disorder and epilepsy, supporting the kindling hypothesis, this model is generally not supported by studies directly assessing it in bipolar subjects.

Neurological Disorders

Mania occurs secondary to neurological conditions between a rate of 2% to 30%. Mania is most commonly seen in right sided lesions, lesions that disconnect the prefrontal cortex, or excitatory lesions in the left hemisphere.

Diseases associated with “secondary mania” include Cushing’s disease, dementia, delirium, meningitis, hyperparathyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, thyrotoxicosis, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, epilepsy, neurosyphilis, HIV dementia, uraemia, as well as traumatic brain injury and vitamin B12 deficiency.

Pathophysiology

Neurobiological and Neuroanatomical Models

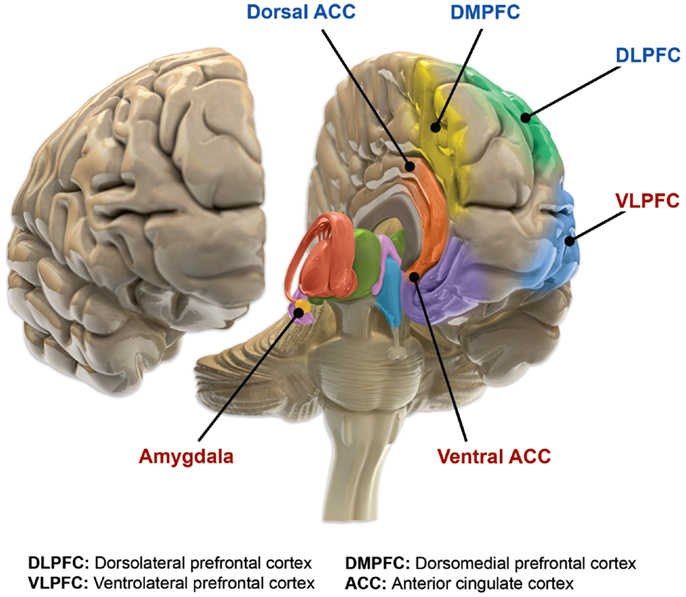

The main loci of neuroimaging and neuropathological findings in bipolar have been proposed to constitute dysfunction in a “visceromotor” network, composed of the mPFC, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), hippocampus, amygdala, hypothalamus, striatum and thalamus.

A model of functional neuroanatomy produced by a workgroup led by Stephen M. Strakowski concluded that bipolar was characterized by reduced connectivity, due to abnormal pruning or development, in the prefrontal-striatal-pallidal-thalamic-limbic network leading to dysregulated emotional responses. This model was supported by a number of common neuroimaging findings. Dysregulation of limbic structures is evinced by the fact that hyperactivity in the amygdala in response to facial stimuli has been consistently reported in mania. While amygdala hyperactivity is not a uniform finding, a number of methodological challenges could explain discrepancies. As most studies utilize fMRI to measure blood-oxygen-level dependent signal, excess baseline activity could result in null findings due to subtraction analysis. Furthermore, heterogenous study design could mask consistent hyperactivity to specific stimuli. Regardless of directionality of amygdala abnormalities, as the amygdala plays a central role in emotional systems, these findings support dysfunctional emotional circuits in bipolar. A general reduction in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activity is observed in bipolar, and is lateralised with regard to mood (i.e. left-depression, right-mania), and may underlie amygdala abnormalities. The dorsal ACC is commonly under-activated in bipolar, and is generally implicated in cognitive functions, while the ventral ACC is hyperactived and implicated in emotional functions. Combined, these abnormalities support the prefrontal-striatal-pallidial-thalamic limbic network underlying dysfunction in emotional regulation in bipolar disorder. Strakowski, along with DelBello and Adler have put forward a model of “anterior limbic” dysfunction in bipolar disorder in a number of papers.

In 2007, Green and colleagues suggested a model of bipolar disorder based on the convergence of cognitive and emotional processing on certain structures. For example, the dACC and sgACC were cognitively associated with impairment of inhibition of emotional responses and self monitoring, which could translate to emotional stimuli having excessive impact on mood. Deficits in working memory associated with abnormal dlPFC function could also translate to impaired ability to represent emotional stimuli, and therefore the impaired ability to reappraise emotional stimuli. Dysfunction in the amygdala and striatum has been associated with attentional biases, and may represent a bottom up mechanism of dysfunctional emotional processing.

Blond et al. proposed a model centred on dysfunction in an “amygdala-anterior paralimbic” system. This model was based on the consistent functional and structural abnormalities in the ventral prefrontal cortex and amygdala. The model also proposes a developmental component of bipolar disorder, wherein limbic abnormalities are present early on, but rostral prefrontal abnormalities develop later in the course. The importance of limbic dysfunction early in development is highlighted by the observation that amygdala lesions early in adulthood produce emotional abnormalities that are not present in people who develop amygdala damage in adulthood.

Lateralised seizure sequelae similar to bipolar has been reported in people with mesial temporal lobe seizures, and provides support for kindling hypotheses about bipolar. This observation led to the first experiments with anticonvulsants in bipolar, which are effective in stabilising mood. Studies reporting reduced markers of inhibitory interneurons post-mortem link the analogy with epilepsy to a possible reduction in inhibitory activity in emotional circuits. Overlap with epilepsy extends to include abnormalities in intracellular signalling, biochemistry in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, and structure and function of the amygdala.

The phenomenology and neuroanatomy of mania secondary to neurological disorders is consistent with findings in primary mania and bipolar disorder. While the diversity of lesions and difficulty in ruling out premorbid psychiatric conditions limit the conclusions that can be drawn, a number of findings are fairly consistent. Structurally, secondary mania is associated with destructive lesions that tend to occur in the right hemisphere, particularly the frontal cortex, mesial temporal lobe and basal ganglia. Functionally hyperactivity in the left basal ganglia and subcortical structures, and hypoactivity in the right ventral prefrontal and basotemporal cortex have been reported in cases of secondary mania. The destruction of right hemisphere or frontal areas is hypothesized to lead to a shift to excessive left sided or subcortical reward processing.

John O. Brooks III put forward a model of bipolar disorder involving dysregulation of a circuit called the “corticolimbic system”. The model was based on more or less consistent observations of reduced activity in the mOFC, vlPFC, and dlPFC, as well as the more or less consistent observations of increased activity in the amygdala, parahippocampal gyrus, cerebellar vermis, anterior temporal cortex, sgACC, and ACC. This pattern of abnormal activity was suggested to contribute to disrupted cognitive and affective processes in bipolar disorder.

Neurocognition

During acute mood episodes, people with bipolar demonstrate mood congruent processing biases. Depressed patients are quicker to react to negatively valenced stimuli, while manic patients are quicker to react to positively valenced stimuli. Acute mood episodes are also associated with congruent abnormalities during decision making tasks. Depressed bipolar is associated with conservative responding, while manic bipolar is associated with liberal responses. Both depression and mania are associated with similar and broad cognitive impairments, including on tests of attention, processing speed, working memory, executive functions, and reaction time.

Clinically, mania is characterised by spending sprees, poor judgement, and inappropriate speech and behaviour. Congruent with this, mania is associated impulsivity on Go-No Go tasks, deficits in emotional decision making, poor probabilistic reasoning, impaired ability on continuous performance tasks, set shifting, and planning. The clinical phenomenology and neurocognitive deficits are similar to those seen in patients with damage to the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), which has been reported in functional neuroimaging studies to be abnormal in bipolar mania. Specifically, reduced blood flow to the lateral OFC has been reported, and may reflect dysfunction that leads to the neurocognitive deficits.

In novel environments, both bipolar manic and bipolar euthymic people demonstrate increased activity, exploration and linear movement that is greater than controls, people with ADHD and people with schizophrenia. Using this behavioural pattern in “reverse translational” studies, this behavioural abnormality has been associated with the cholinergic-aminergic hypothesis, which postulates elevated dopaminergic signalling in mania. Reducing the function of DAT using pharmacological or genetic means produces a similar behavioural pattern in animal models. Pharmacological data is consistent with dysfunction of dopamine in bipolar as some studies have reported hypersensitivity to stimulants (however, some studies have found that stimulants effectively attenuate manic behaviour, and co-morbid ADHD and bipolar are effectively treated with stimulants), and the mechanism of antimanic drugs may involve attenuating dopamine signalling.

Hypersensitivity of reward systems is consistent across mood states in bipolar, and is evident in the prodrome. Increases in goal directed behaviour, risk taking, positive emotions in response to reward, ambitious goal setting and inflexibility in goal directed behaviours are present in euthymia. Neuroimaging studies are consistent with trait hypersensitivity in reward systems, as both mania and depression is associated with elevated resting activity in the striatum, and elevated activity in the striatum and OFC during emotional processing, receipt of reward, and anticipation of reward. Increased activity in the striatum and OFC has also been reported in euthymia during anticipation and receipt of reward, although this finding is extremely inconsistent. These abnormalities may be related to circadian rhythm dysfunction in bipolar, including increased sleep latency, evening preference and poor sleep quality, as the neural systems responsible for both processes are functionally linked. A few lines of evidence suggest that elevated dopamine signalling, possibly due to reduced functionality in DAT, underlie abnormalities in reward function. Dopaminergic drugs such as L-DOPA can precipitate mania, and drugs that attenuate dopaminergic signalling extracellularly (antipsychotics) and intracellularly (lithium) can be efficacious in treating mania. While a large body of translational evidence exists to support DAT hypofunction, in vivo evidence is limited to one study reporting reduced DAT binding in the caudate.

Neuroimaging

Structural

In a review of structural neuroimaging in bipolar disorder, Strakowski proposed dysfunction in an iterative emotional network called the “anterior limbic network”, composed of the thalamus, globus pallidus, striatum, vlPFC, vmPFC, ACC, amygdala, dlPFC, and cerebellar vermis. Structural imaging studies frequently find abnormalities in these regions which are putatively involved in emotional and cognitive functions that are disrupted in bipolar disorder. For example, while structural neuroimaging studies do not always find abnormal PFC volume in bipolar disorder, when they do, PFC volume is reduced. Furthermore, reduced PFC volume is associated with response inhibition deficits and duration of illness. When the PFC at large is not examined and the focus is narrowed to the OFC/vPFC, results more consistently observed reductions, although not in bipolar youth. The sgACC volume is observed to be reduced not only in bipolar disorder, but also in unipolar disorder, as well as people with a family history of affective disorders. Enlargement of the striatum and globus pallidus are commonly found, and although some studies fail to observe this, at least one study has reported no volumetric but subtle morphometric abnormalities.

Structural neuroimaging studies consistently report increased frequency of white matter hyperintensities in people with bipolar. However, whether or not the lesions play a causative role is unknown. It is possible that they are a result of secondary factors, such as the processes underlying an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in bipolar. On the other hand, the observation of reduced white matter integrity in frontal-subcortical regions makes it possible that these hyperintensities play a role dysfunction between limbic and cortical regions. Global brain volume and morphology are normal in bipolar. Regional deficits in volume have been reported in ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal regions. Based on this, it has been suggested that reduced limbic regulation by prefrontal regions plays a role in bipolar. Findings related to the volume of the basal ganglia have been inconsistent.

In healthy controls, amygdala volume is inversely related to age. This relationship is reversed in bipolar disorder, and meta analyses have found reduced amygdala volume in paediatric bipolar disorder, and increased amygdala volume in adulthood. This is hypothesized to reflect abnormal development of amygdala, possibly involving impaired synaptic pruning, although this may reflect medication or compensatory effects; that is, these abnormalities may not be involved in the mechanism of bipolar, and may instead be a consequence.

A 2016 meta analysis reported that bipolar disorder was associated with grey matter reductions bilaterally in the ACC, vmPFC, and insula extending to the temporal lobe. When compared with grey matter reductions in unipolar depression, significant overlap occurred in the insular and medial prefrontal regions. Although unipolar depression was associated with reductions in the ventral most and dorsal most regions of the mPFC and bipolar with a region near the genu of the corpus callosum, the overlap was still statistically significant. Similar to the overlap with major depression, a significant overlap of bipolar disorder with schizophrenia in grey matter volume reduction occurs in the anterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, lateral prefrontal cortex and bilateral insula.

A 2010 meta analysis of differences in regional grey matter volume between controls and bipolar disorder reported reductions bilaterally in the inferior frontal cortex and insula, which extended more prominently in the right side to include the precentral gyrus, as well as grey matter reductions in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (BA24) and anterior cingulate cortex (BA32). One meta analysis reported enlargement of the lateral ventricles and globus pallidus, as well as reductions in hippocampus volume and cross sectional area of the corpus callosum. Another meta analysis reported a similar increase volumes of the globus pallidus and lateral ventricles, as well as increased amygdala volume relative to people with schizophrenia. Reductions have also been reported in the right inferior frontal gyrus, insula, pars triangularis, pars opercularis, and middle and superior temporal gyrus. Structural neuroimaging in people who are susceptible to bipolar disorder (i.e. have a number of relatives with bipolar disorder) have produced few consistent results. Consistent abnormalities in adult first degree relatives include larger insular cortex volumes, while offspring demonstrate increased right inferior frontal gyrus volumes.

The ENIGMA bipolar disorder working group reported cortical thinning in the left Pars opercularis (BA44-inferior frontal gyrus), left fusiform gyrus, left rostral middle frontal cortex, right inferior parietal cortex, along with an increase in the right entorhinal cortex. Duration of illness was associated with reductions bilaterally in the pericalcarine gyrus, left rostral anterior cingulate and right cuneus, along with increases in the right entorhinal cortex. Treatment with lithium was associated with increased cortical thickness bilaterally in the superior parietal gyrus, left paracentral gyrus, and left paracentral lobule. A history of psychosis was associated with reduced surface area in the right frontal pole. Another study on subcortical abnormalities by the same research group reported reductions in the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus, along with ventricular enlargement.

One meta analysis reported that when correcting for lithium treatment, which was associated with increased hippocampal volume, people with bipolar demonstrate reduced hippocampus volume.

White matter is reduced in the posterior corpus callosum, regions adjacent to the anterior cingulate, the left optic radiation, and right superior longitudinal tract, and increased in the cerebellum and lentiform nuclei.

Functional

Studies examining resting blood flow, or metabolism generally observed abnormalities dependent upon mood state. Bipolar depression is generally associated with dlPFC and mOFC hypometabolism. Less consistent associations include reduced temporal cortex metabolism, increased limbic metabolism and reduced ACC metabolism. Mania is also associated with dlPFC and OFC hypometabolism. Limbic hypermetabolism is more consistent than in bipolar depression, but the overall study quality is low due to limitations associated with neuroimaging in acutely manic patients. Another review reported that mania is generally associated with frontal/ventral hypoactivation, while depression is generally associated with the opposite. A degree of lateralization with regard to abnormalities has been reported, with mania being associated with the right hemisphere, and depression the left. Trait abnormalities in euthymic patients have been observed, including hypoactivity in the ventral prefrontal cortex, and hyperactivity in the amygdala.

During cognitive or emotional tasks, functional neuroimaging studies, consistently find hyperactivation of the basal ganglia, amygdala, and thalamus. Prefrontal abnormalities are less consistently reported, although hyperactivation in the ventral prefrontal cortex is a fairly consistent finding. Hyperactivity in the amygdala and hypoactivity in the medial and ventral prefrontal cortex during exposure to emotional stimuli has been interpreted as reflecting dysfunction in emotional regulation circuits. Increased effective connectivity between the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, and elevated striatal responsiveness during reward tasks have been interpreted as hyper-responsiveness in positive emotion and reward circuitry. The abnormal activity in these circuits has been observed in non-emotional tasks, and is congruent with changes in grey and white matter in these circuits. Neural response during reward tasks differentiates unipolar depression from bipolar depression, with the former being associated with reduced neural response and the latter being associated with elevated neural response. An ALE meta analysis of functional neuroimaging comparing adults and adolescents found a larger degree of hyperactivity in the inferior frontal gyrus and precuneus, as well as a larger degree of hypoactivity in the anterior cingulate cortex in adolescents relative to adults.

Regardless of mood state, during response inhibition tasks, people with bipolar disorder underactivate the right inferior frontal gyrus. Changes specific on euthymia include hyperactivations in the left superior temporal gyrus and hypoactivations in the basal ganglia, and changes specific to mania include hyperactivation in the basal ganglia. A meta analysis of fMRI studies reported underactivations in the inferior frontal gyrus and putamen and hyperactivation of the parahippocampus, hippocampus, and amygdala. State specific abnormalities were reported for mania and euthymia. During mania, hypoactivation was significant in the inferior frontal gyrus, while euthymia was associated with hypoactivation of the lingual gyrus and hyperactivation of the amygdala.

A meta analysis using region of interest (as opposed to statistical parametric mapping) analysis reported abnormalities across paradigms for euthymic, depressed, and manic subjects. In bipolar mania, reduced activity was reported in the superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri, while increased activity was reported in the parahippocampal, superior temporal, middle temporal, and inferior temporal gyri. In bipolar depression, reduced activity was reported in the sgACC, ACC, and middle frontal gyrus. In euthymia, reduced activity was reported in the dlPFC, vlPFC, and ACC, while increased activity was reported in the amygdala. During studies examining response to emotional faces, both mania and euthymia were reported to be associated with elevated amygdala activity.

An activation likelihood estimate meta analysis of bipolar studies that used paradigms involving facial emotions reported a number of increases and decreases in activation compared to healthy controls. Elevated activity was reported in the parahippocampal gyrus, putamen, and pulvinar nuclei, while reduced activity was reported bilaterally in the inferior frontal gyrus. Compared to major depressive disorder, bipolar patients overactivated the vACC, pulvinar nucleus, and parahippocampus gyrus/amygdala to a greater degree, while underactivating the dACC. Bipolar subjects overactivated parahippocampus for both fearful and happy expressions, while the caudate and putamen were overactived for happiness and fear respectively. Bipolar subjects also underactivated the ACC for both fearful and happy expressions, while the IFG was underactivated for fearful expressions only. These results were interpreted as reflecting increased engagement with emotionally salient stimuli in bipolar disorder.

Specific symptoms have been linked to various neuroimaging abnormalities in bipolar disorder, as well as schizophrenia. Reality distortion, disorganisation, and psychomotor poverty have been linked to prefrontal, thalamic, and striatal regions in both schizophrenia and bipolar (Table below).

| Symptom Dimension | Implicated Regions in Bipolar | Implicated Regions in Schizophrenia |

|---|---|---|

| Disorganisation | 1. Hypofunction in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC). 2. Hypofunction in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)/ACC. | 1. Hypofunction in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). 2. Hypofunction in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC). 3. Hypofunction in the cerebellum. 4. Hypofunction in the insula. 5. Hypofunction in the temporal cortex. |

| Reality Distortion | 1. Functional abnormalities in prefrontal and thalamic regions. | 1. Reduced grey matter in perisylvian and thalamic regions. 2. Hypofunction of the amygdala, mPFC and hippocampus/parahippocampus. |

| Psychomotor Poverty | 1. Functional abnormalities in the vlPFC and ventral striatum. | 1. Reduced grey matter in the vlPFC, mPFC and dlPFC. 2. Reduced grey matter in the striatum, thalamus, amygdala and temporal cortices. |

Frontal Cortex

Different regions of the ACC have been studied in the literature, with the subgenual (sgACC) and rostral (rACC) parts being largely separated. Grey matter volume in the sgACC has been, albeit with some exceptions, found to be reduced in bipolar. Along with this, bipolar is associated with increased blood flow in the sgACC that normalises with treatment. Congruent with these abnormalities is a reduction in glial cells observed in post mortem studies, and reduced integrity of white matter possibly involving a hemispheric imbalance. Findings in the rACC are largely the same as the sgACC (reduced GM, increased metabolism), although more studies have been carried out on protein expression and neuronal morphology. The rACC demonstrates reduced expression NMDA, kainate and GABA related proteins. These findings may be compensating for increased glutaminergic afferents, evidenced by increased Glx in MRS studies. One VBM study reported reduced grey matter in the dACC. Inconsistent results have been found during functional neuroimaging of cognitive tasks, with both decreased and increased activation being observed. Decreased neuron volume and a congruent increase in neural density have been found in the dACC. Reduced expression of markers of neural connectivity have been reported (e.g. synaptophysin, GAP-43), which is congruent with the abnormal structural connectivity observed in the region.

The orbitofrontal cortex demonstrates reduced grey matter, functional activity, GAD67 mRNA, neuronal volume in layer I, and microstructural integrity in people with bipolar.

Although the role of acute mood states is unknown, grey matter volume is generally reported as reduced in the dlPFC, along with resting and task evoked functional signals. Signals of myelination and density of GABAegic neurons is also reduced in the dlPFC, particularly in layers II-V.

Neurochemistry

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS)

Increased combined glutamine and glutamate (Glx) have been observed globally, regardless of medication status. Increased Glx has been associated with reduced frontal mismatch negativity, interpreted as dysfunction in NMDA signalling. N-acetyl aspartate levels in the basal ganglia are reduced in bipolar disorder, and trends towards increased in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. NAA to creatine ratios are reduced in the hippocampus.

One review of magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies reported increased choline in the basal ganglia, and cingulate as well as a decreased in NAA in the dlPFC and hippocampus. State specific findings were reported to include elevated phosphomonoesters during acute mood states, and reduced inositol with treatment. Another review reported inositol abnormalities in the basal ganglia, and frontal, temporal and cingulate regions. The finding of a trend towards increased NAA concentrations in the dlPFC may be due to medication status, as treatment with lithium or valproate has been noted to lead to null findings, or even elevated levels of NAA in the frontal cortex. In unmedicated populations, reduced NAA consistently found in the prefrontal cortex, particularly the dlPFC.

One meta analysis reported no changes in MRS measured GABA in bipolar disorder.

Monoamines

Various hypotheses related to monoamines have been proposed. The biogenic amine hypothesis posits general dysregulation of monoamines underlies bipolar and affective disorders. The cholinergic aminergic balance hypothesis posits that an increased ratio of cholinergic activity relative to adrenergic signalling underlies depression, while increased adrenergic signalling relative to cholinergic signalling underlies mania. The permissive hypothesis suggests that serotonin is necessary but not sufficient for affective symptoms, and that reduced serotonergic tone is common to both depression and mania.

Studies of the binding potential of dopamine receptor D2 and dopamine transporter have been inconsistent but dopamine receptor D1’s binding potential has been observed to be decreased. Drugs that release dopamine produce effects similar to mania, leading some to hypothesize that mania involves increased catecholaminergic signalling. Dopamine has also been implicated through genetic “reverse translational” studies demonstrating an association between reduced DAT functionality and manic symptoms. The binding potential of muscarinic receptors are reduced in vivo during depression, as well as in post mortem studies, supporting the cholinergic aminergic balance hypothesis.

The role of monoamines in bipolar have been studied using neurotransmitter metabolites. Reduced concentration of homovanillic acid, the primary metabolite of dopamine, in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of people with depression is consistently reported. This finding is related to psychomotor retardation and anhedonia. Furthermore, parkinson’s disease is associated with high rates of depression, and one case study has reported the abolishment of parkinson’s symptoms during manic episodes. The binding potential of VMAT2 is also elevated in bipolar I patients with a history of psychosis, although this finding is inconsistent with finding that valproate increases VMAT2 expression in rodents. One study on DAT binding in acutely depressed people with bipolar reported reductions in the caudate but not putamen.

Studies of serotonin’s primary metabolite 5-HIAA have been inconsistent, although limited evidence points towards reduced central serotonin signalling in a subgroup of aggressive or suicidal patients. Studies assessing the binding potential of the serotonin transporter or serotonin receptors have also been inconsistent, but generally point towards abnormal serotonin signalling. One study reported both increased SERT binding in the insula, mPFC, ACC and thalamus, and decreased SERT binding in the raphe nuclei in acutely depressed bipolar. Serotonin may play a role in mania by increasing the salience of stimuli related to reward.

One more line of evidence that suggests a role of monoamines in bipolar is the process of antidepressant related affective switches. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and more frequently, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are associated with between a 10%-70% risk of affective switch from depression to mania or hypomania, depending upon the criteria used. The more robust association between TCAs and affective switches, as opposed to more selective drugs, has been interpreted as indicating that more extensive perturbation in monoamine systems is associated with more frequent mood switching.

Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal Axis

Bipolar disorder is associated with elevated basal and dexamethasone elicited cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). These abnormalities are particularly prominent in mania, and are inversely associated with antipsychotic use. The incidence of psychiatric symptoms associated with corticosteroids is between 6% and 32%. Corticosteroids may precipitate mania, supporting the role of the HPA axis in affective episodes. Measures from urinary versus salivary cortisol have been contradictory, with one study of the former concluding that HPA hyperactivity was a trait marker, while a study of the latter concluded that no difference in HPA activity exists in remission. Measurement during the morning are thought to be more sensitive due to the cortisol awakening response. Studies are generally more consistent, and observe HPA hyperactivity.

Neurotrophic Factors

Brain derived neurotrophic factor levels are peripherally reduced in both manic and depressive phases.

Intracellular Signalling

The levels of Gαs but not other G proteins is increased in the frontal, temporal and occipital cortices. The binding of serotonin receptors to G proteins is also elevated globally. Leukocyte and platelet levels of Gαs and Gαi is also elevated in those with bipolar disorder. Downstream targets of G protein signalling is also altered in bipolar disorder. Increased levels of adenylyl cyclase, protein kinase A (PKA), and cyclic adenosine monophosphate induced PKA activity are also reported. Phosphoinositide signalling is also altered, with elevated levels of phospholipase C, protein kinase C, and Gαq being reported in bipolar. Elevated cAMP stimulated phosphorylation or Rap1 (a substrate of PKA), along with increased levels of Rap1 have been reported in peripherally collected cells of people with bipolar. Increased coupling of serotonin receptors to G proteins has been observed. While linkage studies performed on genes related to G protein signalling, as well as studies on post mortem mRNA concentration fail to report an association with bipolar disorder, the overall evidence suggests abnormal coupling of neurotransmission systems with G proteins.

Mania may be specifically associated with protein kinase C hyperactivity, although most evidence for this mechanism is indirect. The gene DGKH has been reported in genome wide association studies to be related to bipolar disorder, and it is known to be involved in PKC regulation. Manipulation of PKC in animals produces behavioural phenotypes similar to mania, and PKC inhibition is a plausible mechanism of action for mood stabilisers. Overactive PKC signalling may lead to long term structural changes in the frontal cortex as well, potentially leading to progression of manic symptoms.

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 has been implicated in bipolar disorder, as bipolar medications lithium and valproate have been shown to increase its phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting it. However, some postmortem studies have not shown any differences in GSK-3 levels or the levels of a downstream target β-catenin. In contrast, one review reported a number of studies observing reduced expression of β-catenin and GSK3 mRNA in the prefrontal and temporal cortex.

Excessive response of arachidonic acid signalling cascades in response to stimulation by dopamine receptor D2 or NMDA receptors may be involved in bipolar mania. The evidence for this is primarily pharmacological, based on the observation that drugs that are effective in treating bipolar reduced AA cascade magnitude, while drugs that exacerbate bipolar do the opposite.

Calcium homeostasis may be impaired across all mood states. Elevated basal intracellular, and provoked calcium concentrations in platelets and transformed lymphoblasts are found in people with bipolar. Serum concentrations of calcium are also elevated, and abnormal calcium concentrations in response to stimulation of olfactory neurons is also observed. These findings are congruent with the genetic association of bipolar with CACNAC1, an L-type calcium channel, as well as the efficacy of anti-epileptic agents. Normal platelets placed in plasma from people with bipolar disorder do not demonstrate elevated levels of intracellular calcium, indicating that dysfunction lies intracellularly. One possible mechanism is that elevated inositol triphosphate (IP3) caused by hyperactive neuronal calcium sensor 1 causes excessive calcium release. Serum levels of S100B (a calcium binding protein) are elevated in bipolar mania.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Some researchers have suggested bipolar disorder is a mitochondrial disease. Some cases of familial chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia demonstrate increased rates of bipolar disorder before the onset of CPEO, and the higher rate of maternal inheritance patterns support this hypothesis. Downregulation of genes encoding for mitochondrial subunits, decreased concentration of phosphocreatine, decreased brain pH, and elevated lactate concentrations have also been reported. Mitochondrial dysfunction may be related to elevated levels of the lipid peroxidation marker thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, which are attenuated by lithium treatment.

Neuropathology

A number of abnormalities in GABAergic neurons have been reported in people with bipolar disorder. People with bipolar demonstrate reduced expression of GAD67 in CA3/CA2 subregion of the hippocampus. More extensive reductions of other indicators of GABA function have been reported in the CA4 and CA1. Abnormal expression of kainate receptors on GABAergic cells have been reported, with reductions in GRIK1 and GRIK2 mRNA in the CA2/CA3 being found in people with bipolar. Decreased levels of HCN channels have also been reported, which, along with abnormal glutamate signalling, could contribute to reduced GABAergic tone in the hippocampus.

The observation of increased Glx in the prefrontal cortex is congruent with the observation of reduced glial cell counts and prefrontal cortex volume, as glia play an important role in glutamate homeostasis. Although the number and quality of studies examining NMDA receptor subunits is poor, evidence for reduced NMDA signalling and reduced contribution from the NR2A subunit is consistent.

Decreased neuron density and soma size in the ACC and dlPFC has been observed. The dlPFC also demonstrates reduced glial density, a finding that is less consistent in the ACC. The reduction in cell volume may be due to early stage apoptosis, a mechanism that is supported by studies observing reduced anti-apoptotic gene expression in both peripheral cells and neurons, as well as the reduction in BDNF that is consistently found in bipolar. Reductions in cortical glia are not found across the whole cortex (e.g. somatosensory areas demonstrate normal glial density and counts), indicating that systematic dysfunction in glial cells is not likely; rather, abnormal functionality of connectivity in specific regions may result in abnormal glia, which may in turn exacerbate dysfunction.

Dendritic atrophy and loss of oligodendrocytes is found in the medial prefrontal cortex, and is possibly specific to GABAergic neurons.

Immune Dysfunction

Elevated levels of IL-6, C-reactive protein (CRP) and TNFα have been reported in bipolar. Levels of some (IL-6 and CRP) but not all (TNFα) may be reduced by treatment. Increases in IL-6 have been reported in mood episodes, regardless of polarity. Inflammation has been consistently reported in bipolar disorder, and the progressive nature lies in dysregulation of NF-κB.

You must be logged in to post a comment.