Introduction

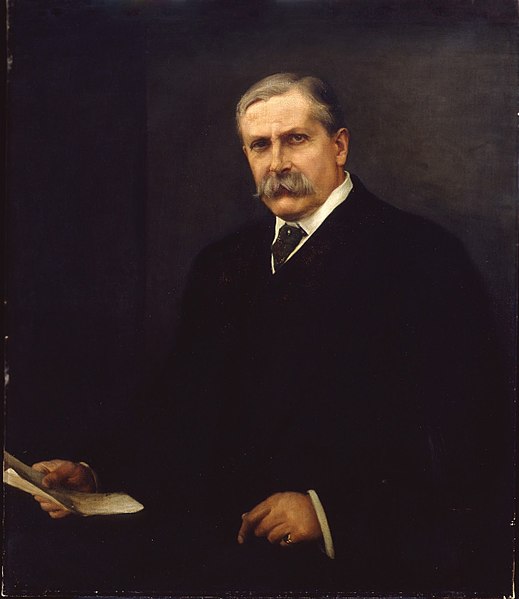

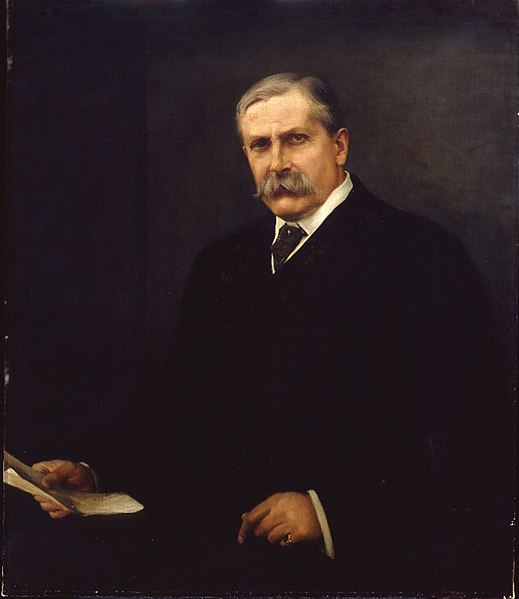

Morgan Scott Peck (1936–2005) was an American psychiatrist and best-selling author who wrote the book The Road Less Traveled (see below), published in 1978.

Early Life

Peck was born on May 22, 1936, in New York City, the son of Zabeth (née Saville) and David Warner Peck, an attorney and judge. His parents were Quakers. Peck was raised a Protestant (his paternal grandmother was from a Jewish family, but Peck’s father identified himself as a WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants) and not as Jewish).

His parents sent him to the prestigious boarding school Phillips Exeter Academy in Exeter, New Hampshire, when he was 13. In his book, The Road Less Traveled, he confides the story of his brief stay at Exeter, and admits that it was a most miserable time. Finally, at age 15, during the spring holiday of his third year, he came home and refused to return to the school, whereupon his parents sought psychiatric help for him and he was (much to his amusement in later life) diagnosed with depression and recommended for a month’s stay in a psychiatric hospital (unless he chose to return to school). He then transferred to Friends Seminary (a private K–12 school) in late 1952, and graduated in 1954, after which he received a BA from Harvard in 1958, and an MD degree from Case Western Reserve University in 1963.

Career

Peck served in administrative posts in the government during his career as a psychiatrist. He also served in the US Army and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. His army assignments included stints as chief of psychology at the Army Medical Centre in Okinawa, Japan, and assistant chief of psychiatry and neurology in the office of the surgeon general in Washington, DC. He was the medical director of the New Milford Hospital Mental Health Clinic and a psychiatrist in private practice in New Milford, Connecticut. His first and best-known book, The Road Less Traveled, sold more than 10 million copies.

Peck’s works combined his experiences from his private psychiatric practice with a distinctly religious point of view. In his second book, People of the Lie, he wrote, “After many years of vague identification with Buddhist and Islamic mysticism, I ultimately made a firm Christian commitment – signified by my non-denominational baptism on the ninth of March 1980…” (Peck, 1983/1988, p11). One of his views was that people who are evil attack others rather than face their own failures.

In December 1984, Peck co-founded the Foundation for Community Encouragement (FCE), a tax-exempt, non-profit, public educational foundation, whose stated mission is “to teach the principles of community to individuals and organizations.” FCE ceased day-to-day operations from 2002 to 2009. In late 2009, almost 25 years after FCE was first founded, the organisation resumed functioning, and began offering community building and training events in 2010.

Personal Life

Peck married Lily Ho in 1959, and they had three children. In 1994, they jointly received the Community of Christ International Peace Award.

While Peck’s writings emphasized the virtues of a disciplined life and delayed gratification, his personal life was far more turbulent. For example, in his book In Search of Stones, Peck acknowledged having extramarital affairs and being estranged from two of his children. In 2004, just a year before his death, Peck was divorced by Lily and married Kathleen Kline Yeates.

Death

Peck died at his home in Connecticut on 25 September 2005. He had had Parkinson’s disease and pancreatic and liver duct cancer. Fuller Theological Seminary houses the archives of his publications, awards, and correspondence.

The Road Less Traveled

The Road Less Traveled, published in 1978, is Peck’s best-known work, and the one that made his reputation. It is, in short, a description of the attributes that make for a fulfilled human being, based largely on his experiences as a psychiatrist and a person.

The book consists of four parts. In the first part Peck examines the notion of discipline, which he considers essential for emotional, spiritual, and psychological health, and which he describes as “the means of spiritual evolution”. The elements of discipline that make for such health include the ability to delay gratification, accepting responsibility for oneself and one’s actions, a dedication to truth, and “balancing”. “Balancing” refers to the problem of reconciling multiple, complex, possibly conflicting factors that impact an important decision—on one’s own behalf or on behalf of another.

In the second part, Peck addresses the nature of love, which he considers the driving force behind spiritual growth. He contrasts his own views on the nature of love against a number of common misconceptions about love, including:

- That love is identified with romantic love (he considers it a very destructive myth when it is solely relying on “falling in love”),

- That love is related to dependency,

- That true love is linked with the feeling of “falling in love”.

Peck argues that “true” love is rather an action that one undertakes consciously to extend one’s ego boundaries by including others or humanity, and is therefore the spiritual nurturing—which can be directed toward oneself, as well as toward one’s beloved.

In the third part Peck deals with religion, and the commonly accepted views and misconceptions concerning religion. He recounts experiences from several patient case histories, and the evolution of the patients’ notion of God, religion, atheism—especially of their own “religiosity” or atheism—as their therapy with Peck progressed.

The fourth and final part concerns “grace”, the powerful force originating outside human consciousness that nurtures spiritual growth in human beings. To focus on the topic, he describes the miracles of health, the unconscious, and serendipity—phenomena which Peck says:

- Nurture human life and spiritual growth,

- Are incompletely understood by scientific thinking,

- Are commonplace among humanity,

- Originate outside the conscious human will.

He concludes that “the miracles described indicate that our growth as human beings is being assisted by a force other than our conscious will”. (Peck, 1978/1992, p.281)

Random House, where the then little-known psychiatrist first tried to publish his original manuscript, turned him down, saying the final section was “too Christ-y.” Thereafter, Simon & Schuster published the work for $7,500 and printed a modest hardback run of 5,000 copies. The book took off only after Peck hit the lecture circuit and personally sought reviews in key publications. Later reprinted in paperback in 1980, The Road first made best-seller lists in 1984 – six years after its initial publication.

People of the Lie

First published in 1983, People of the Lie: Toward a Psychology of Evil [subsequent vols subtitled The Hope For Healing Human Evil and Possession and Group Evil] (ISBN 0 7126 1857 0) followed on from Peck’s first book. Peck describes the stories of several people who came to him whom he found particularly resistant to any form of help. He came to think of them as evil and goes on to describe the characteristics of evil in psychological terms, proposing that it could become a psychiatric diagnosis. Peck points to narcissism as a type of evil in this context.

Theories

Love

His perspective on love (in The Road Less Traveled) is that love is not a feeling, it is an activity and an investment. He defines love as, “The will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth” (Peck, 1978/1992, p.85). Peck expands on the work of Thomas Aquinas over 700 years ago, that love is primarily actions towards nurturing the spiritual growth of another.

Peck seeks to differentiate between love and cathexis. Cathexis is what explains sexual attraction, the instinct for cuddling pets and pinching babies’ cheeks. However, cathexis is not love. All the same, love cannot begin in isolation; a certain amount of cathexis is necessary to get sufficiently close to be able to love.

Once through the cathexis stage, the work of love begins. It is not a feeling. It consists of what you do for another person. As Peck says in The Road Less Traveled, “Love is as love does.” It is about giving yourself and the other person what they need to grow.

Discipline

The Road Less Traveled begins with the statement “Life is difficult”. Life was never meant to be easy and is essentially a series of problems which can either be solved or ignored. Peck wrote of the importance of discipline, describing four aspects of it:

- Delaying gratification: Sacrificing present comfort for future gains.

- Acceptance of responsibility: Accepting responsibility for one’s own decisions.

- Dedication to truth: Honesty, both in word and deed.

- Balancing: Handling conflicting requirements.

Peck argues that these are techniques of suffering, that enable the pain of problems to be worked through and systematically solved, producing growth. He argues that most people avoid the pain of dealing with their problems and suggests that it is through facing the pain of problem-solving that life becomes more meaningful.

Neurotic and Legitimate Suffering

Peck believes that it is only through suffering and agonizing using the four aspects of discipline (delaying gratification, acceptance of responsibility, dedication to truth, and balancing) that we can resolve the many puzzles and conflicts that we face. This is what he calls undertaking legitimate suffering. Peck argues that by trying to avoid legitimate suffering, people actually ultimately end up suffering more. This extra unnecessary suffering is what Scott Peck terms neurotic suffering. He references Carl Jung ‘Neurosis is always a substitute for legitimate suffering’. Peck says that our aim must be to eliminate neurotic suffering and to work through our legitimate suffering to achieve our individual goals.

Evil

Peck discusses evil in his three-volume book People of the Lie, as well as in a chapter of The Road Less Traveled. Peck characterises evil as a malignant type of self-righteousness in which there is an active rather than passive refusal to tolerate imperfection (sin) and its consequent guilt. This syndrome results in a projection of evil onto selected specific innocent victims (often children), which is the paradoxical mechanism by which the People of the Lie commit their evil. Peck argues that these people are the most difficult of all to deal with, and extremely hard to identify. He describes in some detail several individual cases involving his patients. In one case which Peck considers as the most typical because of its subtlety, he describes Roger, a depressed teenage son of respected, well-off parents. In a series of parental decisions justified by often subtle distortions of the truth, they exhibit a consistent disregard for their son’s feelings, and a consistent willingness to destroy his growth. With false rationality and normality, they aggressively refuse to consider that they are in any way responsible for his resultant depression, eventually suggesting his condition must be incurable and genetic.

Peck makes a distinction between those who are on their way to becoming evil and those who have already crossed the line and are irretrievably evil. In the first instance, he describes George. Peck says, “Basically, George, you’re a kind of a coward. Whenever the going gets a little bit rough, you sell out.” Of note, this is the kind of evil that inspired the film Session 9. When asked where evil lives, Simon concludes, “I live in the weak and the wounded.” On the other hand, those who have crossed the line and are irretrievably evil are described as having malignant narcissism.

Some of Peck’s conclusions about the psychiatric condition that he designates as “evil” are derived from his close study of one patient he names Charlene. Although Charlene is not dangerous, she is ultimately unable to have empathy for others in any way. According to Peck, people like her see others as playthings or tools to be manipulated for their own uses or entertainment. Peck states that these people are rarely seen by psychiatrists, and have never been treated successfully.

Evil is described by Peck as “militant ignorance”. The original Judeo-Christian concept of “sin” is as a process that leads us to “miss the mark” and fall short of perfection. Peck argues that while most people are conscious of this, at least on some level, those who are evil actively and militantly refuse this consciousness. Peck considers those he calls evil to be attempting to escape and hide from their own conscience (through self-deception), and views this as being quite distinct from the apparent absence of conscience evident in sociopathy.

According to Peck, an evil person:

- is consistently self-deceiving, with the intent of avoiding guilt and maintaining a self-image of perfection

- deceives others as a consequence of their own self-deception

- projects his or her evils and sins onto very specific targets (scapegoats) while being apparently normal with everyone else (“their insensitivity toward him was selective” (Peck, 1983/1988, p.105))

- commonly hates with the pretence of love, for the purposes of self-deception as much as deception of others

- abuses political (emotional) power (“the imposition of one’s will upon others by overt or covert coercion” (Peck, 1978/1992, p.298))

- maintains a high level of respectability, and lies incessantly to do so

- is consistent in his or her sins. Evil persons are characterised not so much by the magnitude of their sins, but by their consistency (of destructiveness)

- is unable to think from the viewpoint of their victim (scapegoating)

- has a covert intolerance to criticism and other forms of narcissistic injury

Most evil people realise the evil deep within themselves, but are unable to tolerate the pain of introspection, or admit to themselves that they are evil. Thus, they constantly run away from their evil by putting themselves in a position of moral superiority and putting the focus of evil on others. Evil is an extreme form of what Peck, in The Road Less Traveled, calls a character and personality disorder.

Using the My Lai massacre as a case study, Peck also examines group evil, discussing how human group morality is strikingly less than individual morality. Partly, he considers this to be a result of specialization, which allows people to avoid individual responsibility and pass the buck, resulting in a reduction of group conscience.

Though the topic of evil has historically been the domain of religion, Peck makes great efforts to keep much of his discussion on a scientific basis, explaining the specific psychological mechanisms by which evil operates. He was also particularly conscious of the danger of a psychology of evil being misused for personal or political ends. Peck considered that such a psychology should be used with great care, as falsely labelling people as evil is one of the very characteristics of evil. He argued that a diagnosis of evil should come from the standpoint of healing and safety for its victims, but also with the possibility even if remote, that the evil themselves may be cured.

Ultimately, Peck says that evil arises out of free choice. He describes it thus: Every person stands at a crossroads, with one path leading to God, and the other path leading to the devil. The path of God is the right path, and accepting this path is akin to submission to a higher power. However, if a person wants to convince himself and others that he has free choice, he would rather take a path which cannot be attributed to its being the right path. Thus, he chooses the path of evil.

Peck also discussed the question of the devil. Initially he believed, as with “99% of psychiatrists and the majority of clergy” (Peck, 1983/1988, p.182), that the devil did not exist; but, after starting to believe in the reality of human evil, he then began to contemplate the reality of spiritual evil. Eventually, after having been referred several possible cases of possession and being involved in two exorcisms, he was converted to a belief in the existence of Satan. Peck considered people who are possessed as being victims of evil, but of not being evil themselves. Peck, however, considered possession to be rare, and human evil common. He did believe there was some relationship between Satan and human evil, but was unsure of its exact nature. Peck’s writings and views on possession and exorcism are to some extent influenced and based on specific accounts by Malachi Martin; however, the veracity of these accounts and Peck’s own diagnostic approach to possession have both since been questioned by a Catholic priest who is a professor of theology. It has been argued that it is not possible to find formal records to establish the veracity of Father Malachi Martin’s described cases of possession, as all exorcism files are sealed by the Archdiocese of New York, where all but one of the cases took place.

The Four Stages of Spiritual Development

Peck postulates that there are four stages of human spiritual development:

- Stage I is chaotic, disordered, and reckless. Very young children are in Stage I. They may defy and disobey and are unwilling to accept a will greater than their own. They are egoistical and lack empathy for others. Criminals are often people who have never grown out of Stage I.

- Stage II is the stage at which a person has blind faith in authority figures and sees the world as divided simply into good and evil, right and wrong, us and them. Once children learn to obey their parents and other authority figures (often out of fear or shame), they reach Stage II. Many religious people are Stage II. With blind faith comes humility and a willingness to obey and serve. The majority of conventionally moralistic, law-abiding citizens never move out of Stage II.

- Stage III is the stage of scientific scepticism and questioning. A Stage III person does not accept claims based on faith, but is only convinced with logic. Many people working in scientific and technological research are in Stage III. Often they reject the existence of spiritual or supernatural forces, since these are difficult to measure or prove scientifically. Those who do retain their spiritual beliefs move away from the simple, official doctrines of fundamentalism.

- Stage IV is the stage at which an individual enjoys the mystery and beauty of nature and existence. While retaining scepticism, s/he starts perceiving grand patterns in nature and develops a deeper understanding of good and evil, forgiveness and mercy, compassion and love. His/her religiousness and spirituality differ from that of a Stage II person, in the sense that s/he does not accept things through blind faith or out of fear, but from genuine belief. S/he does not judge people harshly or seek to inflict punishment on them for their transgressions. This is the stage of loving others as yourself, losing your attachment to your ego, and forgiving your enemies. Stage IV people are labelled mystics.

Peck argues that while transitions from Stage I to Stage II are sharp, transitions from Stage III to Stage IV are gradual. Nonetheless, these changes are noticeable and mark a significant difference in the personality of the individual.

Community Building

In his book The Different Drum: Community Making and Peace, Peck says that community has three essential ingredients:

- Inclusivity

- Commitment

- Consensus

Based on his experience with community building workshops, Peck says that community building typically goes through four stages:

- Pseudocommunity: In the first stage, well-intentioned people try to demonstrate their ability to be friendly and sociable, but they do not really delve beneath the surface of each other’s ideas or emotions. They use obvious generalities and mutually established stereotypes in speech. Instead of conflict resolution, pseudocommunity involves conflict avoidance, which maintains the appearance or facade of true community. It also serves only to maintain positive emotions, instead of creating a safe space for honesty and love through bad emotions as well. While they still remain in this phase, members will never really obtain evolution or change, as individuals or as a bunch.

- Chaos: The first step towards real positivity is, paradoxically, a period of negativity. Once the mutually sustained façade of bonhomie is shed, negative emotions flood through: members start to vent their mutual frustrations, annoyances, and differences. It is a chaotic stage, but Peck describes it as a “beautiful chaos” because it is a sign of healthy growth (this relates closely to Dabrowski’s concept of disintegration).

- Emptiness: To transcend the stage of “Chaos”, members are forced to shed that which prevents real communication. Biases and prejudices, need for power and control, self-superiority, and other similar motives which are only mechanisms of self-validation and/or ego-protection, must yield to empathy, openness to vulnerability, attention, and trust. Hence, this stage does not mean people should be “empty” of thoughts, desires, ideas or opinions. Rather, it refers to emptiness of all mental and emotional distortions which reduce one’s ability to really share, listen to, and build on those thoughts, ideas, etc. It is often the hardest step in the four-level process, as it necessitates the release of patterns which people develop over time in a subconscious attempt to maintain self-worth and positive emotion. While this is therefore a stage of “Fana (Sufism)” in a certain sense, it should be viewed not merely as a “death”, but as a rebirth—of one’s true self at the individual level, and at the social level of the genuine and True community.

- True community: Having worked through emptiness, the people in the community enter a place of complete empathy with one another. There is a great level of tacit understanding. People are able to relate to each other’s feelings. Discussions, even when heated, never get sour, and motives are not questioned. A deeper and more sustainable level of happiness obtains between the members, which does not have to be forced. Even, and perhaps especially, when conflicts arise, it is understood that they are part of positive change.

The four stages of community formation are somewhat related to a model in organization theory for the five stages that a team goes through during development. These five stages are:

- Forming where the team members have some initial discomfort with each other, but nothing comes out in the open. They are insecure about their role and position with respect to the team. This corresponds to the initial stage of pseudocommunity.

- Storming where the team members start arguing heatedly, and differences and insecurities come out in the open. This corresponds to the second stage given by Scott Peck, namely chaos.

- Norming where the team members lay out rules and guidelines for interaction that help define the roles and responsibilities of each person. This corresponds to emptiness, where the community members think within and empty themselves of their obsessions to be able to accept and listen to others.

- Performing where the team finally starts working as a cohesive whole, and to effectively achieve the tasks set of themselves. In this stage individuals are aided by the group as a whole, where necessary, to move further collectively than they could achieve as a group of separated individuals.

- Transforming This corresponds to the stage of true community. This represents the stage of celebration, and when individuals leave, as they invariably must, there is a genuine feeling of grief, and a desire to meet again. Traditionally, this stage was often called “Mourning”.

It is in this third stage that Peck’s community-building methods differ in principle from team development. While teams in business organisations need to develop explicit rules, guidelines and protocols during the norming stage, the emptiness stage of community building is characterised, not by laying down the rules explicitly, but by shedding the resistance within the minds of the individuals.

Peck started the Foundation for Community Encouragement (FCE) to promote the formation of communities, which, he argues, are a first step towards uniting humanity and saving us from self-destruction.

The Blue Heron Farm is an intentional community in central North Carolina, whose founders stated that they were inspired by Peck’s writings on community. Peck himself had no involvement with this project, however.

The Exosphere Academy of Science & the Arts uses community building in their teaching methodology to help students practice deeper communication, remove their “masks”, and feel more comfortable collaborating and building innovative projects and startups.

Based on research by Robert E. Roberts (1943–2013), Chattanooga Endeavors has used Community Building since 1996 as a group intervention to improve the learning experience of former offenders participating in work-readiness training. Roberts’ research demonstrates that groups that are exposed to Community Building achieve significantly better training outcomes.

Characteristics of True Community

Peck describes what he considers to be the most salient characteristics of a true community:

- Inclusivity, commitment, and consensus: members accept and embrace each other, celebrating their individuality and transcending their differences. They commit themselves to the effort and the people involved. They make decisions and reconcile their differences through consensus.

- Realism: members bring together multiple perspectives to better understand the whole context of the situation. Decisions are more well-rounded and humble, rather than one-sided and arrogant.

- Contemplation: members examine themselves. They are individually and collectively self-aware of the world outside themselves, the world inside themselves, and the relationship between the two.

- A safe place: members allow others to share their vulnerability, heal themselves, and express who they truly are.

- A laboratory for personal disarmament: members experientially discover the rules for peacemaking and embrace its virtues. They feel and express compassion and respect for each other as fellow human beings.

- A group that can fight gracefully: members resolve conflicts with wisdom and grace. They listen and understand, respect each other’s gifts, accept each other’s limitations, celebrate their differences, bind each other’s wounds, and commit to a struggle together rather than against each other.

- A group of all leaders: members harness the “flow of leadership” to make decisions and set a course of action. It is the spirit of community itself that leads, and not any single individual.

- A spirit: The true spirit of community is the spirit of peace, love, wisdom and power. Members may view the source of this spirit as an outgrowth of the collective self or as the manifestation of a Higher Will.

This page is based on the copyrighted Wikipedia article < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M._Scott_Peck#Love >; it is used under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA). You may redistribute it, verbatim or modified, providing that you comply with the terms of the CC-BY-SA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.