Introduction

Twelve-step programmes are international mutual aid programs supporting recovery from substance addictions, behavioural addictions and compulsions. Developed in the 1930s, the first twelve-step programme, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), founded by Bill Wilson and Bob Smith, aided its membership to overcome alcoholism. Since that time dozens of other organisations have been derived from AA’s approach to address problems as varied as drug addiction, compulsive gambling, sex, and overeating. All twelve-step programmes utilise a version of AA’s suggested twelve steps first published in the 1939 book Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How More Than One Hundred Men Have Recovered from Alcoholism.

As summarised by the American Psychological Association (APA), the process involves the following:

- Admitting that one cannot control one’s alcoholism, addiction, or compulsion;

- Coming to believe in a Higher Power that can give strength;

- Examining past errors with the help of a sponsor (experienced member);

- Making amends for these errors;

- Learning to live a new life with a new code of behaviour; and

- Helping others who suffer from the same alcoholism, addictions, or compulsions.

Overview

Twelve-step methods have been adapted to address a wide range of alcoholism, substance abuse, and dependency problems. Over 200 mutual aid organisations – often known as fellowships—with a worldwide membership of millions have adopted and adapted AA’s 12 Steps and 12 Traditions for recovery. Narcotics Anonymous was formed by addicts who did not relate to the specifics of alcohol dependency.

Demographic preferences related to the addicts’ drug of choice has led to the creation of Cocaine Anonymous, Crystal Meth Anonymous and Marijuana Anonymous. Behavioural issues such as compulsion for or addiction to gambling, crime, food, sex, hoarding, getting into debt and work are addressed in fellowships such as Gamblers Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, Sexaholics Anonymous and Debtors Anonymous.

Auxiliary groups such as Al-Anon and Nar-Anon, for friends and family members of alcoholics and addicts, respectively, are part of a response to treating addiction as a disease that is enabled by family systems. Adult Children of Alcoholics (ACA or ACOA) addresses the effects of growing up in an alcoholic or otherwise dysfunctional family. Co-Dependents Anonymous (CoDA) addresses compulsions related to relationships, referred to as co-dependency.

Brief History

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), the first twelve-step fellowship, was founded in 1935 by Bill Wilson and Dr. Robert Holbrook Smith, known to AA members as “Bill W.” and “Dr. Bob”, in Akron, Ohio. In 1946 they formally established the twelve traditions to help deal with the issues of how various groups could relate and function as membership grew. The practice of remaining anonymous (using only one’s first names) when interacting with the general public was published in the first edition of the AA Big Book.

As AA chapters were increasing in number during the 1930s and 1940s, the guiding principles were gradually defined as the Twelve Traditions. A singleness of purpose emerged as Tradition Five: “Each group has but one primary purpose—to carry its message to the alcoholic who still suffers”. Consequently, drug addicts who do not suffer from the specifics of alcoholism involved in AA hoping for recovery technically are not welcome in “closed” meetings unless they have a desire to stop drinking alcohol.

The principles of AA have been used to form numerous other fellowships specifically designed for those recovering from various pathologies; each emphasizes recovery from the specific malady which brought the sufferer into the fellowship.

The Twelve Steps

The following are the original twelve steps as published by Alcoholics Anonymous:[11]

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

- Came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

- Continued to take personal inventory, and when we were wrong, promptly admitted it.

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Where other twelve-step groups have adapted the AA steps as guiding principles, step one is generally updated to reflect the focus of recovery. For example, in Overeaters Anonymous, the first step reads, “We admitted we were powerless over compulsive overeating—that our lives had become unmanageable.” The third step is also sometimes altered to remove gender-specific pronouns.

The Twelve Traditions

The Twelve Traditions accompany the Twelve Steps. The Traditions provide guidelines for group governance. They were developed in AA in order to help resolve conflicts in the areas of publicity, politics, religion, and finances. Alcoholics Anonymous’ Twelve Traditions are:

- Our common welfare should come first; personal recovery depends upon AA unity.

- For our group purpose there is but one ultimate authority—a loving God as He may express Himself in our group conscience. Our leaders are but trusted servants; they do not govern.

- The only requirement for AA membership is a desire to stop drinking.

- Each group should be autonomous except in matters affecting other groups or AA as a whole.

- Each group has but one primary purpose—to carry its message to the alcoholic who still suffers.

- An AA group ought never endorse, finance, or lend the AA name to any related facility or outside enterprise, lest problems of money, property, and prestige divert us from our primary purpose.

- Every AA group ought to be fully self-supporting, declining outside contributions.

- Alcoholics Anonymous should remain forever non-professional, but our service centers may employ special workers.

- AA, as such, ought never be organised; but we may create service boards or committees directly responsible to those they serve.

- Alcoholics Anonymous has no opinion on outside issues; hence the AA name ought never be drawn into public controversy.

- Our public relations policy is based on attraction rather than promotion; we need always to maintain personal anonymity at the level of press, radio, and films.

- Anonymity is the spiritual foundation of all our traditions, ever reminding us to place principles before personalities.

The Process

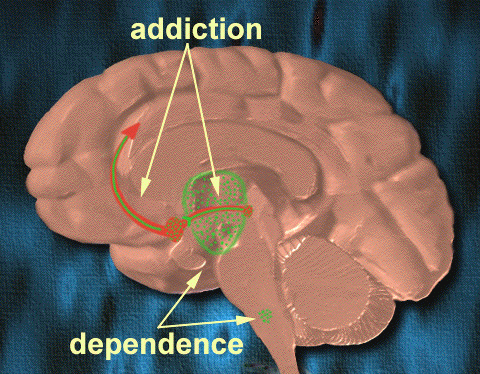

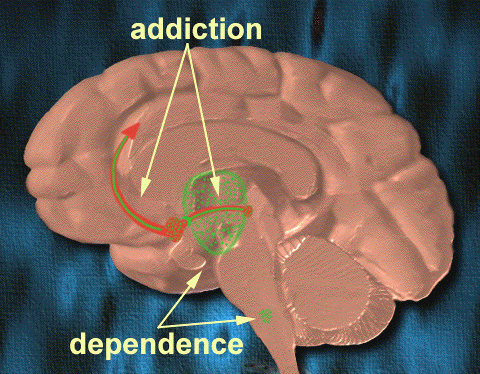

In the twelve-step programme, the human structure is symbolically represented in three dimensions: physical, mental, and spiritual. The problems the groups deal with are understood to manifest themselves in each dimension. For addicts and alcoholics, the physical dimension is best described by the allergy-like bodily reaction resulting in the compulsion to continue using substances even when it’s harmful or wanting to quit. The statement in the First Step that the individual is “powerless” over the substance-abuse related behaviour at issue refers to the lack of control over this compulsion, which persists despite any negative consequences that may be endured as a result.

The mental obsession is described as the cognitive processes that cause the individual to repeat the compulsive behaviour after some period of abstinence, either knowing that the result will be an inability to stop or operating under the delusion that the result will be different. The description in the First Step of the life of the alcoholic or addict as “unmanageable” refers to the lack of choice that the mind of the addict or alcoholic affords concerning whether to drink or use again. The illness of the spiritual dimension, or “spiritual malady,” is considered in all twelve-step groups to be self-centeredness. The process of working the steps is intended to replace self-centeredness with a growing moral consciousness and a willingness for self-sacrifice and unselfish constructive action. In twelve-step groups, this is known as a “spiritual awakening.” This should not be confused with abreaction, which produces dramatic, but temporary, changes. As a rule, in twelve-step fellowships, spiritual awakening occurs slowly over a period of time, although there are exceptions where members experience a sudden spiritual awakening.

In accordance with the First Step, twelve-step groups emphasize self-admission by members of the problem they are recovering from. It is in this spirit that members often identify themselves along with an admission of their problem, often as “Hi, I’m [first name only], and I’m an alcoholic”.

Sponsorship

A sponsor is a more experienced person in recovery who guides the less-experienced aspirant (“sponsee”) through the program’s twelve steps. New members in twelve-step programmes are encouraged to secure a relationship with at least one sponsor who both has a sponsor and has taken the twelve steps themselves. Publications from twelve-step fellowships emphasize that sponsorship is a “one on one” non-hierarchical relationship of shared experiences focused on working the Twelve Steps. According to Narcotics Anonymous:

Sponsors share their experience, strength, and hope with their sponsees… A sponsor’s role is not that of a legal adviser, a banker, a parent, a marriage counsellor, or a social worker. Nor is a sponsor a therapist offering some sort of professional advice. A sponsor is simply another addict in recovery who is willing to share his or her journey through the Twelve Steps.

Sponsors and sponsees participate in activities that lead to spiritual growth. Experiences in the programme are often shared by outgoing members with incoming members. This rotation of experience is often considered to have a great spiritual reward. These may include practices such as literature discussion and study, meditation, and writing. Completing the programme usually implies competency to guide newcomers which is often encouraged. Sponsees typically do their Fifth Step, review their moral inventory written as part of the Fourth Step, with their sponsor. The Fifth Step, as well as the Ninth Step, have been compared to confession and penitence. Michel Foucault, a French philosopher, noted such practices produce intrinsic modifications in the person—exonerating, redeeming and purifying them; relieves them of their burden of wrong, liberating them and promising salvation.

The personal nature of the behavioural issues that lead to seeking help in twelve-step fellowships results in a strong relationship between sponsee and sponsor. As the relationship is based on spiritual principles, it is unique and not generally characterised as “friendship”. Fundamentally, the sponsor has the single purpose of helping the sponsee recover from the behavioural problem that brought the sufferer into twelve-step work, which reflexively helps the sponsor recover.

A study of sponsorship as practiced in Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous found that providing direction and support to other alcoholics and addicts is associated with sustained abstinence for the sponsor, but suggested that there were few short-term benefits for the sponsee’s one-year sustained abstinence rate.

Effectiveness

Alcoholics Anonymous is the largest of all of the twelve-step programmes (from which all other twelve-step programmes are derived), followed by Narcotics Anonymous; the majority of twelve-step members are recovering from addiction to alcohol or other drugs. The majority of twelve-step programmes, however, address illnesses other than substance addiction. For example, the third-largest twelve-step programme, Al-Anon, assists family members and friends of people who have alcoholism and other addictions. About twenty percent of twelve-step programmes are for substance addiction recovery, the other eighty percent address a variety of problems from debt to depression. It would be an error to assume the effectiveness of twelve-step methods at treating problems in one domain translates to all or to another domain.

A 2020 Cochrane review of Alcoholics Anonymous showed that participation in AA resulted in more alcoholics being abstinent from alcohol and for longer periods of time than cognitive behavioural therapy and motivational enhancement therapy, and as effective as these in other measures. The 2020 review did not compare twelve step programmes to the use of disulfiram or naltrexone, though some patients did receive these medications. These medications are considered the standard of care in alcohol use disorder treatment among medical experts and have demonstrated efficacy in randomised controlled trials in promoting alcohol abstinence. A systematic review published in 2017 found that twelve-step programmes for reducing illicit drug use are neither better nor worse than other interventions.

Criticism

In the past, some medical professionals have criticised 12-step programmes as “a cult that relies on God as the mechanism of action” and as lacking any experimental evidence in favour of its efficacy. Ethical and operational issues had prevented robust randomised controlled trials from being conducted comparing 12-step programmes directly to other approaches. More recent studies employing non-randomised and quasi-experimental studies have shown 12-step programmes provide similar benefit compared to motivational enhancement therapy (MET) and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and were more effective in producing continuous abstinence and remission compared to these approaches.

Confidentiality

The Twelve Traditions encourage members to practice the spiritual principle of anonymity in the public media and members are also asked to respect each other’s confidentiality. This is a group norm, however, and not legally mandated; there are no legal consequences to discourage those attending twelve-step groups from revealing information disclosed during meetings. Statutes on group therapy do not encompass those associations that lack a professional therapist or clergyman to whom confidentiality and privilege might apply. Professionals and paraprofessionals who refer patients to these groups, to avoid both civil liability and licensure problems, have been advised that they should alert their patients that, at any time, their statements made in meetings may be disclosed.

Cultural Identity

One review warned of detrimental iatrogenic effects of twelve-step philosophy and labelled the organisations as cults, while another review asserts that these programs bore little semblance to religious cults and that the techniques used appeared beneficial to some. Another study found that a twelve-step program’s focus on self-admission of having a problem increases deviant stigma and strips members of their previous cultural identity, replacing it with the deviant identity. Another study asserts that the prior cultural identity may not be replaced entirely, but rather members found adapted a bicultural identity.

This page is based on the copyrighted Wikipedia article < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelve-step_program >; it is used under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA). You may redistribute it, verbatim or modified, providing that you comply with the terms of the CC-BY-SA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.