1.0 Introduction

“Lifestyle modifications can assume especially great importance in individuals with serious mental illness. Many of these individuals are at a high risk of chronic diseases associated with sedentary behavior and medication side effects, including diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and cardiovascular disease. An essential component of lifestyle modification is exercise. The importance of exercise is not adequately understood or appreciated by patients and mental health professionals alike. Evidence has suggested that exercise may be an often-neglected intervention in mental health care.” (Sharma, Madaaan & Petty, 2006).

This article provides an overview of exercise for mental health.

It is now a well-known ‘secret’ that exercise (and, let us not forget, physical activity) has an important part to play in both our physical health and mental health.

I think we can safely state that you (the reader) almost certainly already know that an inactive lifestyle contributes to chronic miseries such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, osteoporosis, and an earlier death. You may also be one of the third of people who have resolved to exercise more (well, maybe get Christmas out the way first!).

However, how often do people consider the contribution of physical exercise to their mental health? And, with an expected rise in the number of people with mental health issues, it is more important than ever to extol the benefits of exercise.

“It is estimated there will be nearly 8 million more adults in the UK by 2030. If prevalence rates for mental disorders stay the same (at around one in four), that is some 2 million more adults with mental health problems than today. It is also estimated that there will be one million more children and young people in the UK by 2030. Again, if prevalence rates for mental disorders stay the same (at around one in ten), that is some 100,000 more children and young people with mental health problems than today.” (Mental Health Foundation, 2013, p.2).

Exercising releases natural chemicals, such as serotonin, dopamine and endorphins into the body, which help to boost mood. High levels of serotonin are linked to elevated mood while low levels are associated with depression. Exercise can also help reduce the amount of harmful chemicals in the body that are produced when an individual is stressed.

2.0 Benefits of Exercise

In simple terms, exercise provides a variety of short- and long-term, and obvious and less obvious, benefits.

- Exercising benefits nearly all aspects of a person’s health (CDC, 2019) – In addition to aiding control weight, it can improve the chances of living longer, maintaining/improving the strength of bones and muscles, and an individual’s mental health.

- When an individual does not get enough exercise, they are at increased risk for health problems – these include cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure (hypertension), type 2 diabetes, some cancers, and metabolic syndrome (CDC, 2019).

- Exercise also increases a variety of substances that play an important role in brain function (Section 4.0).

- Exercise can help prevent (certain) mental illnesses and is an important part of treatment.

Exercise is well-known to stimulate the body to produce our natural feel-good hormones which can make problems seem more manageable.

The simple act of focusing on exercise can give an individual a break from current concerns and damaging self-talk. Further, depending on the activity, individuals may benefit from calming exercises, be energised, and get outside or interact with others, all of which are known to improve mood and general health.

With this in mind, the health benefits from regular exercise that should be emphasised and reinforced by every professional (e.g. mental health, medical, nursing, physiotherapist, fitness/exercise) to individuals include:

- Improved sleep;

- Increased interest in sex;

- Better endurance;

- Stress relief;

- Improvement in mood;

- Increased energy and stamina;

- Reduced tiredness that can increase mental alertness;

- Weight reduction;

- Reduced cholesterol; and

- Improved cardiovascular fitness.

2.1 What is the Importance of Exercise for those with Mental Health Problems?

Having a mental health problem can put an individual at a higher risk of developing a serious physical health problem. For example, individuals with mental health problems are:

- Twice as likely to die from heart disease (Harris & Barraclough, 1998).

- Four times as likely to die from respiratory disease (Phelan et al., 2001).

- On average, likely to die between 10 and 17 years earlier than the general population, if they have schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

- This may be due to a number of factors including poor diet, exercise and social conditions. People may also be slower to seek help, and doctors can sometimes fail to spot physical health problems in people with severe mental health problems.

3.0 Linking Physical Health and Mental Health

It is still very common for physical health and mental health, aka mind and body, to be treated separately (both medically and in general), although attitudes are slowly changing.

There is an increasing pool of evidence that suggests that exercise is not only necessary for the maintenance of good mental health, but it can be used to treat even chronic mental illness.

For example, it is now clear that exercise reduces the likelihood of depression and also maintains mental health as people age. On the treatment side, exercise appears to be as good as existing pharmacological interventions across a range of conditions, such as mild to moderate depression, dementia, and anxiety, and even reduces cognitive issues in schizophrenia.

The question you might now be asking is, how?

3.1 Exercise directly affects the Brain

Aerobic exercises (such as jogging, swimming, cycling, walking, gardening, and dancing) have been proved to reduce anxiety and depression (Guzszkowska, 2004). These improvements in mood are proposed to be caused by exercise-induced increase in blood circulation to the brain and by an influence on the hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis and, thus, on the physiologic reactivity to stress (Guszkowska, 2004). It has been suggested that this physiologic influence is probably mediated by the communication of the HPA axis with several regions of the brain, including:

- The limbic system, which controls motivation and mood;

- The amygdala, which generates fear in response to stress; and

- The hippocampus, which plays an important part in memory formation as well as in mood and motivation.

However, it is important to note that other hypotheses that have been proposed to explain the beneficial effects of physical activity on mental health which include (Peluso & Andrade, 2005):

- Distraction;

- Self-efficacy; and

- Social interaction.

In 2017, Firth and colleagues suggested that regular exercise increases the volume of certain brain regions – in part through:

- Better blood supply that improves neuronal health by improving the delivery of oxygen and nutrients; and

- An increase in neurotrophic factors and neurohormones that support neuron signaling, growth, and connections.

They also stated that of critical importance for mental health is the hippocampus (an area of the brain involved in memory, emotion regulation, and learning). Studies in other animals show convincingly that exercise leads to the creation of new hippocampal neurons (neurogenesis), with preliminary evidence suggesting this is also true in humans.

“Aerobic exercise interventions may be useful for preventing age-related hippocampal deterioration and maintaining neuronal health.” (Firth et al., 2017, p.230).

There is an accumulating evidence base that various mental health conditions are associated with reduced neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

The evidence is particularly strong for depression and, interestingly, many anti-depressants – that were once thought to work through their effects on the serotonin system – are now known to increase neurogenesis (Anacker et al., 2011) in the hippocampus.

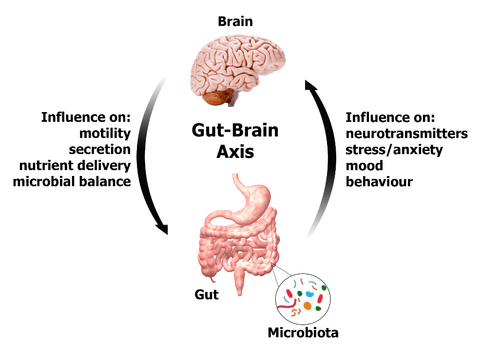

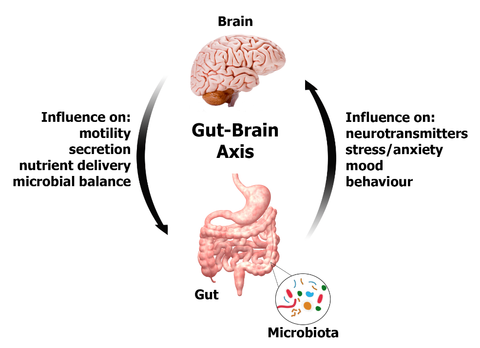

Serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine is a monoamine neurotransmitter. It has a popular image as a contributor to feelings of well-being and happiness, though its actual biological function is complex and multifaceted, modulating cognition, reward, learning, memory, and numerous physiological processes. It sends signals between nerve cells. Serotonin is found mostly in the digestive system, although it is also in blood platelets and throughout the central nervous system. Serotonin is made from the essential amino acid tryptophan.

3.2 What does this Mean in Theory?

Theories suggest that newborn hippocampal neurons are likely to be particularly important for storing new memories and keeping old and new memories separate and distinct – Meaning neurogenesis allows a healthy level of flexibility in the use of existing memories, and in the flexible processing of new information.

Frequently, mental ill health is characterised by a cognitive inflexibility that:

- Keeps the individual repeating unhelpful behaviours;

- Restricts their ability to process or even acknowledge new information; and

- Reduces their ability to use what they already know to see new solutions or to change.

Consequently, this suggests that it is plausible that exercise leads to better mental health, in general, through its effects on systems that increase the capacity for mental flexibility.

4.0 Substances that Play an Important Role in Brain Function

- BDNF (brain derived neurotrophic factor) is a protein that creates and protects neurons (nerve cells) in the brain helps these cells to transmit messages more efficiently, and regulates depression-like behaviours (Vithlani et al., 2013; Sleiman et al., 2016).

- Endorphins are a type of chemical messenger (neurotransmitter) that is released when we experience stress or pain to reduce their negative effects and increase pleasure throughout the body (Bortz, Angwin & Mefford, 1981).

- Endorphins are also responsible for the euphoric feeling known as a “runner’s high” that happens after long periods of intense exercise.

- Serotonin is another neurotransmitter that increases during exercise. It plays a role in sending messages about appetite, sleep, and mood (Young, 2007).

- It is the target of medications known as SSRIs or SNRIs, which are used to treat anxiety and depression.

- Dopamine is involved in controlling movement and the body’s reward response system. Due to its role in how the body perceives rewards, it is heavily involved with addictions.

- When amounts of this chemical messenger are low, it is linked to mental health conditions including depression, schizophrenia, and psychosis (Grace, 2016).

- Glutamate and GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid) both act to regulate the activity of nerve cells in the parts of the brain that process visual information, determine heart rate, and affect emotions and the ability to think clearly (Maddock et al., 2016).

- Low levels of GABA have been linked to depression, anxiety, PTSD, and mood disorders (Streeter et al., 2012).

5.0 Exercise as Treatment in Mental Health

- Just one hour of exercise a week is related to lower levels of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders (de Graaf & Monshouwer, 2011).

- Among people in the US, those who make regular physical activity a part of their routines are less likely to have depression, panic disorder, and phobias (extreme fears) (Goodwin, 2003).

- One study found that for people with anxiety, exercise had similar effects to cognitive behavioural therapy in reducing symptoms (Wipfli, Rethorst & Landers, 2008).

- For people with schizophrenia, yoga is the most effective form of exercise for reducing positive and negative symptoms associated with the disorder (Vancampfort et al., 2012).

- While structured group programmes can be effective for individuals with serious mental illness, lifestyle changes that focus on the accumulation and increase of moderate-intensity activity throughout the day may be the most appropriate for most patients (Richardson et al., 2005).

- Interestingly, adherence to physical activity interventions in psychiatric patients appears to be comparable to that in the general population (Sharma et al., 2006).

- Exercise is especially important in patients with schizophrenia since these patients are already vulnerable to obesity and also because of the additional risk of weight gain associated with antipsychotic treatment, especially with the atypical antipsychotics.

- GP surgeries, across the UK, are starting to routinely prescribe exercise as a treatment for a variety of conditions, including depression.

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that if an individual has mild to moderate depression, taking part in three exercises sessions a week can help.

6.0 Examples of How Exercise can Support Mood, Well-being, and Mental Health

- General:

- Exercise improves mental health by reducing anxiety, depression, and negative mood and by improving self-esteem and cognitive function (Callaghan, 2004).

- Exercise has also been found to alleviate symptoms such as low self-esteem and social withdrawal (Peluso & Andrade, 2005).

- Depression:

- According to findings from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2019), if an individual keeps active they are less likely to experience symptoms of depression.

- The reason for this is because exercise has a certain effect on chemicals in our brains, such as dopamine and serotonin, which affect both your mood and thinking.

- Just by adding a bit more physical activity into their daily life, an individual can create new activity patterns in the brain which can boost their mood.

- However, the individual should take it at their own pace, and not attempt difficult new exercises straight away.

- Anxiety:

- Frequent exercise can help people with anxiety to be less likely to panic when they experience ‘fight-or-flight’ sensations.

- This is because the human body produces many of the same physical reactions, including heavy perspiration (sweating) and increased heart rate, in response to exercise.

- A study by the American Psychological Association in 2011 demonstrated that over a two-week exercise programme, a test group of 60 people who took part in exercises showed significant improvements in anxiety sensitivity compared to a control group (Weir, 2011).

- Stress:

- Stress does not just affect an individual’s brain, with its many nerve connections, it also has an impact on the way they feel physically.

- This can manifest as muscle tension, especially in the face, neck and shoulders.

- However, research by the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (2018) shows that physical activity is helpful when stress has depleted an individual’s energy – because exercise produces endorphins that act as a natural painkiller.

- And, these endorphins help relieve tension in the body and relax muscles, which can alleviate stress.

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD):

- Although the exact cause of ADHD is unknown, research suggests that exercise can have a similar effect on the brain as medication for ADHD does.

- This is because exercise releases chemicals in the brain such as norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine, which help to improve focus and attention.

- And, physical activity can help to improve mood, concentration and motivation – all of which help to reduce symptoms of ADHD.

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Trauma:

- Activities such as sailing, hiking, and mountain biking, and rock climbing have particularly been shown to alleviate the effects of PTSD and trauma.

- By focusing on their body and how it feels when exercising, an individual can help their nervous system become ‘unstuck’, so that it moves out of the immobilisation stress response that can create PTSD or trauma.

- Memory:

- As well as improving our concentration, physical activity can also help age-related memory problems.

- A study in 2012 (Sifferlin, 2012) found that people in their 70s who participated in more physical exercise, such as walking several times a week, experienced fewer signs of ageing in the brain than those who were less physically active.

7.0 How much Exercise should an Individual Be Doing?

In the UK, the NHS (2019) suggests that adults (19 to 64) should:

- Do some form of physical activity every day – with any activity being better than none.

- Do strengthening activities that work all the major muscles (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders and arms) on at least 2 days a week.

- Do at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity a week or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity a week.

- Moderate activity includes: brisk walking, water aerobics, riding a bike, dancing, tennis, pushing a lawn mower, hiking, and roller blading.

- Vigorous activity includes: Jogging or running, swimming fast, riding a bike fast or on hills, walking up the stairs, sports (e.g. football, rugby, netball, and hockey), skipping rope, aerobics, gymnastics, and martial arts.

- Reduce time spent sitting or lying down, and break up long periods of not moving with some activity.

Do not be disheartened, as exercise does not have to be done for hours on end. For example, ten minutes of moderate or vigorous activity at a time, fifteen times a week will see the individual achieve the recommended amount.

Muscle strengthening activities should be incorporated into an individual’s exercise routine twice a week. This includes yoga, lifting weights, resistance band exercises, and things like press/push-ups, and sit-ups. An individual’s muscles should be tired by the time they are finished with their exercises, but the individual should make sure they are not trying to lift too much too soon, or they could injure themselves.

In 2013, Rethorst and Trivedi, psychiatrists, demonstrated that three or more sessions per week of aerobic exercise or resistance training, for 45 to 60 minutes per session, can help treat even chronic depression. In terms of intensity, for aerobic exercise, Rethorst and Trivedi (2013) recommend achieving a heart rate that is 50-85% of the individual’s maximum heart rate (HRmax). For resistance training, they recommend a variety of upper and lower body exercises – three sets of eight repetitions at 80% of 1-repetition maximum (RM, that is, 80% of the maximum weight that the individual can lift one time). They suggest that effects tend to be noticed after about four weeks (which incidentally is how long neurogenesis takes, refer to Section 3.1), and training should be continued for 10-12 weeks for the greatest anti-depressant effect.

With contemporary trends for exercise ‘quick fixes’, this may seem like a lot of exercise, but no worthwhile mental health fix comes for free. Remember, even exercise levels below these recommended amounts are still beneficial and, of course, the side effects (e.g. weight loss, increased energy, better skin, improved physical health, etc.) are very acceptable.

8.0 Mental Health and the Fitness Industry

“Physical health is one thing, but mental health, despite being something which can dramatically impact and affect someone’s life, is an often overlooked component of a person’s wellbeing.” (Waterman, 2018).

Traditionally, determining whether an individual was ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’ ultimately come down to how the individual looked, their fitness levels, their diet, and whether they suffered from any specific physical health conditions.

The fitness industry is geared towards physical health improvements, and health questionnaires (also known as Physical Activity Readiness – Questionnaires, PAR-Q, or Exercise Readiness Questionnaire, ERQ) are largely focussed on physical health conditions.

Catch all questions that are typically asked include:

- Do you have any other medical conditions?

- Do you have, or have you had any illnesses recently?

- Do you know of any other reason why you should not do physical activity?

- Is stress from daily living an issue in your life?

- Are you on medication?

- Do you take any medications, either prescription or non-prescription, on a regular basis?

- What is the medication for?

- How does this medication affect your ability to exercise or achieve your fitness goals?

Questionnaires can vary from basic information collection (1 page) to fairly data intensive (6-8 pages), but questions asked and information collected vary vastly between fitness providers.

“In fitness, we get so caught up talking about bodyfat levels, bodyweight, aerobic fitness abilities, and food choices, that we neglect to address hugely important factors which affect our mental health.” (Waterman, 2018).

9.0 Summary

An individual does not have to have a gym membership to make exercise a part of their life! Picking physical activities that are easy to incorporate into the things/activities they already do and having a strong social support system are important in incorporating exercise into an individual’s routine.

Exercise also may help to meet the need for cost-effective and accessible alternative therapies for depressive disorders – particularly for the substantial number of individuals who do not recover with currently available treatments.

It is important to note that even small improvements in exercise levels or diet create a positive upward spiral that increases the sensitivity of the dopamine receptors that signal reward, so that exercise will eventually become rewarding, even if that seems unimaginable at the outset!

10.0 Useful Publications

11.0 References

Anacker, C., Zunszain, P.A., Cattaneo, A., Carvalho, L.A., Garabedian, M.J., Thuret, S., Price, J. & Pariante, C.M. (2011) Antidepressants increase human hippocampal neurogenesis by activating the glucocorticoid receptor. Molecular Psychiatry. 16(7), pp.738-750. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.26.

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. (2018) Exercise for Stress and Anxiety. Available from World Wide Web: https://adaa.org/living-with-anxiety/managing-anxiety/exercise-stress-and-anxiety. [Accessed: 27 November, 2019].

Bortz, W.M., Angwin, P., Mefford, I.N. (1981) Catecholamines, Dopamine, and Endorphin Levels during Extreme Exercise. New England Journal of Medicine. 305, pp.466-467.

Callaghan, P. (2004) Exercise: A Neglected Intervention in Mental Health Care? Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing. 11, pp.476-483.

CDC (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention). (2019) Physical Activity Basics. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/index.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fphysicalactivity%2Fbasics%2Fpa-health%2Findex.htm. [Accessed: 26 November, 2019].

Firth, J., Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., Schuch, F., Lagopoulos, J., Rosenbaum, S. & Ward, P.B. (2017) Effect of aerobic exercise on hippocampal volume in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. NeuroImage. 166, pp.230-238.

Goodwin, R.D. (2003) Association between physical activity and mental disorders among adults in the United States. Preventative Medicine. 36(6), pp.698–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00042-2.

Grace, AA. (2016). Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 17(8), 524-532. http://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.57.

Guszkowska, M. (2004) Effects of Exercise on Anxiety, Depression and Mood [in Polish]. Psychiatria Polska. 38(4), pp.611-620.

Harris, E.C. & Barraclough, B. (1998) Excess Mortality of Mental Disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 173, pp.11-53.

Maddock, R.J., Casazza, G.A., Fernandez, D.H. & Maddock, M.I. (2016) Acute Modulation of Cortical Glutamate and GABA Content by Physical Activity. Journal of Neuroscience. 36(8), pp.2449. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3455-15.2016.

Mental Health Foundation. (2013) Starting Today: The Future of Mental Health Services. Final Inquiry Report, September 2013. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/starting-today.pdf. [Accessed: 27 November, 2019].

Peluso, M.A. & Andrade, L.H. (2005) Physical Activity and Mental Health: The Association between Exercise and Mood. Clinics. 60, pp.61-70.

Phelan, M., Stradins, L. & Morrison, S. (2001) Physical Health of People with Severe Mental Illness. BMJ. 322(7284), pp.443-444.

Rethorst, C.D. & Trivedi, M.H. (2013) Evidence-based recommendations for the prescription of exercise for major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 19(3), pp.204-212. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000430504.16952.3e.

Richardson, C.R., Faulkner, G., McDevitt, J., Skrinar, G.S., Hutchinson, D.S. & Piette, J.D. (2005) Integrating Physical Activity into Mental Health Services for Persons with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. 56(3), pp.324-331.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2019) Support, Care and Treatment. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/treatments-and-wellbeing. [Accessed: 27 November, 2019].

Sifferlin, A. (2012) Exercise Trumps Brain Games in Keeping our Minds Intact. Available from World Wide Web: http://healthland.time.com/2012/10/23/exercise-trumps-brain-games-in-keeping-our-minds-intact/. [Accessed: 27 November, 2019].

Sleiman, S.F., Henry, J., Al-Haddad, R., El Hayek, L., Haider, E.A., Stringer, T., Ulja, D., Karuppagounder, S.S., Holson, E.B., Ratan, R.R., Ninan, I. & Chao, M.V. (2016) Exercise promotes the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) through the action of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. eLife. 2016;5:e15092 doi:10.7554/eLife.15092.

Streeter, C.C. Gerbarg, P.L., Saper, R.B., Ciraulo, D.A. & Brown, R.P. (2012) Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Medical Hypotheses. 78(5), pp.571-579. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. Epub 2012 Feb 24.

ten Have, M., de Graaf, R. & Monshouwer, K. (2011) Physical exercise in adults and mental health status findings from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS). Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 71(5):342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.04.001.

Vancampfort, D., Vansteelandt, K., Scheewe, T., Probst, M., Knapen, J., De Herdt, A. & De Hert, M. (2012) Yoga in schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. (2012). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 126(1), pp.12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01865.x. Epub 2012 Apr 6.

Vithlani, M., Hines, R.M., Zhong, P., Terunuma, M., Hines, D.J., Revilla-Sanchez, R., Jurd, R., Haydon, P., Rios, M., Brandon, N. Yan, Z. & Moss, S.J. (2013) The Ability of BDNF to Modify Neurogenesis and Depressive-Like Behaviors Is Dependent upon Phosphorylation of Tyrosine Residues 365/367 in the GABAA-Receptor γ2 Subunit. The Journal of Neuroscience. 33(39), pp.15567-15577. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1845-13.2013.

Waterman, A. (2018) Mental health: The forgotten side of the fitness industry. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/life/health/mental-health-the-forgotten-side-of-the-fitness-industry-36982847.html. [Accessed: 27 November, 2019].

Weir, K. (2011) The exercise effect: Evidence is mounting for the benefits of exercise, yet psychologists don’t often use exercise as part of their treatment arsenal. Here’s more research on why they should. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/12/exercise. [Accessed: 27 November, 2019].

Wipfli, B.M., Rethorst, C.D. & Landers, D.M. (2008) The anxiolytic effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose-response analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 30(4), pp.392-410.

Young, S.N. (2007) How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 32, pp.394-399.

You must be logged in to post a comment.