Certificate: Mental Health Awareness for Sport & Physical Activity

Research Paper Title

The efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders: a meta-review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials.

Background

The role of nutrition in mental health is becoming increasingly acknowledged. Along with dietary intake, nutrition can also be obtained from “nutrient supplements”, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, amino acids and pre/probiotic supplements.

Recently, a large number of meta-analyses have emerged examining nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders.

Methods

To produce a meta-review of this top-tier evidence, the researchers identified, synthesised and appraised all meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) reporting on the efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in common and severe mental disorders.

Results

Their systematic search identified 33 meta-analyses of placebo-controlled RCTs, with primary analyses including outcome data from 10,951 individuals. The strongest evidence was found for PUFAs (particularly as eicosapentaenoic acid) as an adjunctive treatment for depression.

More nascent evidence suggested that PUFAs may also be beneficial for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, whereas there was no evidence for schizophrenia.

Folate-based supplements were widely researched as adjunctive treatments for depression and schizophrenia, with positive effects from RCTs of high dose methylfolate in major depressive disorder.

There was emergent evidence for N-acetylcysteine as a useful adjunctive treatment in mood disorders and schizophrenia.

All nutrient supplements had good safety profiles, with no evidence of serious adverse effects or contraindications with psychiatric medications.

Conclusions

In conclusion, clinicians should be informed of the nutrient supplements with established efficacy for certain conditions (such as eicosapentaenoic acid in depression), but also made aware of those currently lacking evidentiary support.

Future research should aim to determine which individuals may benefit most from evidence-based supplements, to further elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Reference

Firth, J., Teasdale, S.B., Allott, K., Siskind, D., Marz, W., Cotter, J., Veronese, N., Schuch, F., Smith, L., Solmi, M., Carvalho, A.F., Vancampfort, D., Berk, M., Stubbs, B> & Sarris, J. (2019) The efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders: a meta-review of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 18, pp.308-324.

Introduction

In their Annual Report and Accounts 2017/2018, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) stated that there were “0.5 million work-related stress, depression or anxiety cases (new or long-standing) in 2016/17” (HSE, 2018, p.9).

What is the HSE?

“HSE is the independent regulator for work-related health and safety in Great Britain. We are committed to playing our part in the wider health and safety system to ensure that others play theirs in creating healthier, safer workplaces. We also deliver wider functions such as regulatory schemes intended to protect the health of people and the environment, balancing the economic and social benefits that chemicals offer to society.” (HSE, 2018, p.10).

HSE and Stress

HSE states that where (work-related) stress is prolonged it can lead to both physical and psychological damage, including anxiety and depression, and that work can also aggravate pre-existing conditions, and problems at work can bring on symptoms or make their effects worse.

They go on to state that whether work is causing the health issue or aggravating it, employers have a legal responsibility to help their employees. Work-related mental health issues must to be assessed to measure the levels of risk to staff. Where a risk is identified, steps must be taken to remove it or reduce it as far as reasonably practicable.

Some employees will have a pre-existing physical or mental health condition when recruited or may develop one caused by factors that are not work-related factors.

Employers may have further legal requirements, to make reasonable adjustments under equality legislation.

Information about employing people with a disability can be found on GOV.UK or from the Equality and Human Rights Commission in England, Scotland, and Wales.

There is advice for line managers to help them support their employees with mental health conditions.

What is the Stevenson Farmer ‘Thriving at Work’ Review?

In 2017, the UK government commissioned Lord Stevenson and Paul Farmer (Chief Executive of Mind) to independently review the role employers can play to better support individuals with mental health conditions in the workplace.

The ‘Thriving at Work’ report sets out a framework of actions – called ‘Core Standards’ – that the reviewers recommend employers of all sizes can and should put in place.

The core standards were designed to help employers improve the mental health of their workplace and enable individuals with mental health conditions to thrive.

By taking action on work-related stress, either through using the HSE Management Standards or an equivalent approach, employers would be able to meet parts of the core standards framework, as they would:

Can Mental Health and Work-related Stress be Interlinked?

Work-related stress and mental health problems often go together and the symptoms can be very similar. For example, work-related stress can aggravate an existing mental health problem, making it more difficult to control. And, if work-related stress reaches a point where it has triggered an existing mental health problem, it becomes hard to separate one from the other.

Common mental health problems and stress can exist independently. For example, an individual can experience work-related stress and physical changes such as high blood pressure, without having anxiety, depression or other mental health problems. They can also have anxiety and depression without experiencing stress.

The key differences between them are their cause(s) and the way(s) they are treated.

However, an individual can have these sorts of problems with no obvious causes. Employers can help manage and prevent stress by improving conditions at work. But they also have a role in making adjustments and helping the individual manage a mental health problem at work.

Linking HSE’s Management Standards, and Mental Ill Health and Stress

Although stress can lead to physical and mental health conditions, and can aggravate existing conditions, the good news is that it can be tackled.

By taking action to remove or reduce stressors, an employer can:

HSE’s Management Standards approach to tackling work-related stress establishes a framework to help employers tackle work-related stress and, as a result, also reduce the:

The Management Standards approach can help employers put processes in place for properly managing work-related stress. By covering six key areas of work design employers will be taking steps that will:

References

HSE (Health & Safety Executive). (2018) Annual Report and Accounts 2017/18. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.hse.gov.uk/aboutus/reports/ara-2017-18.pdf. [Accessed: 18 November, 2019].

HSE (Health & Safety Executive). (2019) Mental Health. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/mental-health.htm. [Accessed: 18 November, 2019].

1.0 Introduction

Workplaces have habitually been seen as key settings for a range of health promotion initiatives targeted at working people.

Programmes that assist, for example, employees to reduce or give up smoking, eat more healthily or improve their fitness are common. However, the published research shows that there are few evidence-based interventions carried out in or by workplaces to address common mental health problems among employees.

The research literature on programmes that address the mental health of employees has been dominated by interventions targeted either at the whole population of employees, for example stress inoculation, or at those deemed to be at high risk of stress-related disorders, for example stress reduction or management.

These approaches mirror physical health interventions aimed at individual behaviour change and do not offer a model for organisational approaches to these issues.

2.0 The Workplace and Employers

While evidence tells us that workplaces are not the sole or principal setting for delivering interventions for people with common mental health problems, employers nevertheless remain key partners.

They do, after all, have a contractual and personal relationship with their employees, as well as statutory health, safety and disability accommodation duties.

The focus of employers’ role in the management of common mental health problems among employees should be to ensure that the working environment supports retention and rehabilitation. Recent policy recommendations have highlighted this responsibility.

For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) reviewed some of the literature on mental health and work, as suggested by experts in the field. In the absence of randomised control trials (RCT’s) on the topic under review, Workplace Mental Health suggests that employers take a strategic and co-ordinated approach to workplace wellbeing; that employers provide opportunities for flexible working; and that line managers promote and support wellbeing among staff (NICE, 2009).

The NHS Health and Wellbeing Review (DH, 2009) acknowledged not only that some employees are likely to have existing common mental health problems, but also that the nature of the working environment can sometimes have a negative impact on staff mental wellbeing. Among the review’s recommendations were that all NHS bodies should ensure that their management practices adhered to the Health and Safety Executive’s management standards for the control of work-related stress; that more investment was needed to attract people to take up occupational medicine; that all managers are trained in the management of people with mental health problems; and that all NHS bodies give priority to the implementation of the NICE guidance on workplace mental health in order to signal their commitment to staff health and wellbeing (NICE, 2009).

A parallel piece of work complemented the NHS Health and Wellbeing Review and described findings from the Practitioner Health Programme. The intervention is targeted at doctors and dentists with health problems who might be reluctant to seek help through usual channels. In its first year, a total of 184 practitioners within the M25 area had accessed the service: 57% with mental health problems and 23% with addiction issues (Crawford et al., 2009; Ipsos MORI, 2009; Smauel et al., 2009; DH, 2010).

The UK Government’s Foresight scientific review on Mental Capital and Wellbeing (Foresight, 2008) included a chapter devoted to work (Dewe & Kompier, 2008), recommending that employers foster work environments conducive to good mental wellbeing and the enhancement of mental capital, for example, by extending the right to flexible working. The chapter also highlighted the importance of:

All of these recommendations mirror the findings of a longitudinal cohort study on workplace factors that may help to reduce depressive symptoms (Brenninkmeijer et al., 2008). Work resumption, partial and full, and the employer changing the employee’s tasks, promoted a more favourable outcome. However, these findings emerged from the Netherlands, where the employer and employee have a legal obligation to sit together and discuss solutions to obstacles preventing return to work, an important factor associated with the decrease in long-term disability in that country (Reijenga et al., 2006). Perhaps a policy shift will be necessary to allow workplaces in the UK to play a central role in the management of common mental health problems.

3.0 References

Brenninkmeijer, V., Houtman, I. & Blonk, R. (2008) Depressed and absent from work: predicting prolonged depressive symptomatology among employees. Occupational Medicine. 58, pp.295-301.

Crawford, J., Shafrir, A. et al. (2009) A Systematic Review of the Health of Health Practitioners. Edinburgh: Institute of Occupational Medicine. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.iom-world.org. [Accessed: 24 November, 2019].

Dewe, P. & Kompier, M. (2008) Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project. Wellbeing and Work: Future challenges. London: The Government Office for Science. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.foresight.gov.uk/Mental_Capital/Wellbeing_and_work.pdf. [Accessed: 24 November, 2019].

DH (Department of Health). (2009) NHS Health and Wellbeing Review. Interim Report. London: Department of Health. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.nhshealthandwellbeing.org/InterimReport.html. [Accessed: 24 November, 2019].

DH (Department of Health). (2010) Invisible Patients: Report of the working group on the health of health professionals. London: Department of Health. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_113540. [Accessed: 24 November, 2019].

Foresight. (2008) Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project. Final Project Report. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.foresight.gov.uk/Mental_Capital/Mental_capital_&_wellbeing_Exec_Sum.pdf. [Accessed: 24 November, 2019].

Ipsos MORI (2009) Fitness to Practice: The health of healthcare professionals. London.

NICE (2009a) Workplace Mental Health. Available from World Wide Web: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PHG/Wave12/82. [Accessed: 24 November, 2019].

Reijenga , F.A., Veerman, T. & van den Berg, N. (2006) Evaluation Law Gatekeeper Improvement. Report 363. Gravenhage: Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid NL.

Samuel, B., Harvey, S.B., Laird, B. et al. (2009) The Mental Health of Health Care Professionals: A review for the Department of Health. London: King’s College London.

For some people mental health problems may be a ‘one off’, causing distress for a relatively short period in a person’s life. For others, mental health problems may be longer term, possibly returning at different times or causing long-term challenges. However, one thing is clear, people can and do recover from mental health problems – no matter how serious or long term they are.

Recovery is a deeply personal and individual process. For some it means getting back to ‘normal’ or back to the way things were before a period of illness. Others consider it to mean not experiencing symptoms of the illness any more. People who have had long-term problems often describe a process of growth and development, in the presence or absence of symptoms. Many people describe it as a journey in which they become active in managing and controlling their own well-being and recovery.

Recovery is a key message in Mental Health First Aid. The presence of hope and the expectation of recovery is one of the most important forms of support we can give a person with a mental health problem.

The things that help everyone recover from physical illness or painful life events are the same things that help people recover from mental illness.

From a Mental Health Perspective, What is Recovery?

Recovery is being able to live a meaningful and satisfying life, as defined by each person, in the presence or absence of symptoms.

It is about having control over your own life.

Each individual’s recovery, like their experience of mental health problems or illness, is a unique and deeply personal process.

People trained in mental health first aid are not expected to have specialist knowledge of different groups’ attitudes and beliefs about mental health.

The most important thing is to avoid making assumptions about the person to whom you are offering support.

For instance, do not assume that the person shares the same attitudes as you hold.

When suggesting that a person seeks further help, it is best to ask who they would feel most comfortable approaching rather than immediately suggesting their general practitioner (GP).

Similarly, it is best to use simple language like ‘low mood’ or ‘sadness’ rather than using terms like depression when talking about a person’s mood or feelings.

These guidelines hold true in any situation. It is always better to avoid making assumptions about another person and to check out that person’s feelings and preferences before offering advice and support.

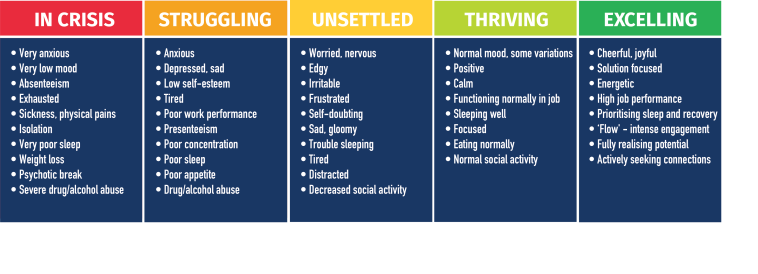

Mental health and illness has sometime been described as a spectrum.

People at one end of the line or spectrum are very well, and those at the other end are very unwell with a serious mental illness.

In the middle might be people who have minor mental health problems.

This idea is not a very helpful method to understand mental health, as it can lead us to make false assumptions.

For example, one may falsely assume that most people are ‘well’ and that a few people, who are a long way removed at the other end of the spectrum, are ‘ill’ or ‘mad’.

This assumption creates a distance between people and causes fear. Another assumption is that once you know your place on the spectrum, it is where you will stay unless something dramatic happens to change it.

This denies the fact that we can make a big difference to our own mental health, both positively and negatively.

It also does not take account of the fact that our mental health changes a lot over relatively short periods of time.

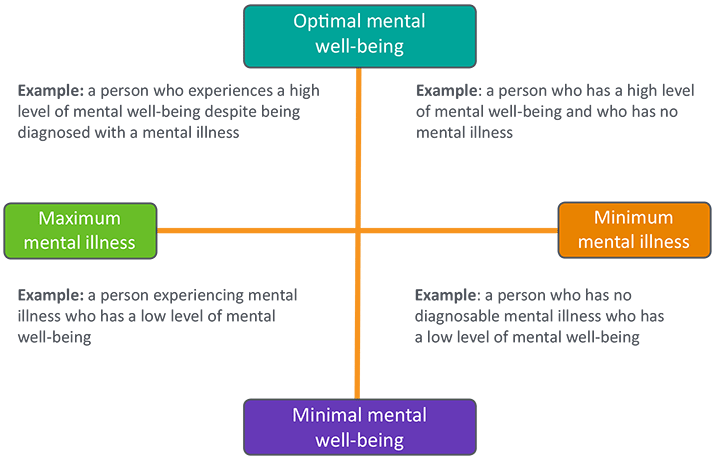

A different and more helpful way of thinking about mental health is the continuum (Figure 1).

The four quadrants of the mental health continuum represent different possible times and situations in a person’s life.

On the right hand side of the diagram, two possible situations are described. Even if a person has no diagnosable illness, they can have either positive or negative mental well-being. Usually the person’s mental health will be affected by life events. If faced with redundancy or the break up of a long-term relationship, the person may find themselves at the lower end of the continuum, experiencing poor mental well-being. If things are going well and the person is looking after their emotional, mental, and physical health they may be higher up the continuum.

Similarly, on the left hand side of the diagram we see that a person with a diagnosed illness can also be experiencing either positive or negative mental well-being.

With the right treatment and proper supports in place, the person can live a happy and fulfilled life whether or not they are experiencing symptoms. Living life to the full may involve having meaningful things to do, having good relationships, a satisfying social life, and good self esteem. On the other hand, without the right treatment and support the person may experience negative mental health.

Being at the lower end of the mental health continuum puts people at greater risk of suicide, whether they have a mental illness or not.

Given that 1 in 4 adults will experience mental health problems at some time in their lives, we can see that it is possible for us to move into all four corners of the continuum at different times.

Knowing that mental health changes over time can help us to look after our own well-being. It can also help us to be more understanding and supportive of others when they are experiencing poor mental health.

There are other ways to look at the mental health continuum.

This article provides an overview of things that one might wish to consider regarding mental health and insurance.

Mental health conditions might not be as easy to pin down as physical health conditions, but insurers are increasingly recognising the need to provide cover and support to those suffering with a mental health condition.

One in four people in the United Kingdom (UK) will be affected by a mental health problem in any given year and, of these, around four million will also struggle with their financial wellbeing.

The insurance industry is aware of the importance and value of insurance in protecting individuals when life does not go to plan. And, with this in mind, the insurance industry continues to demonstrate increasing commitment to aiding those suffering from a mental health problem. In 2017, mental health was the most common cause of claim on income protection policies in the UK.

The insurance industry continues to engage with the third sector (aka charities) and healthcare industries to promote greater access to insurance for individuals with mental health conditions and has repeatedly emphasised its commitment to aiding people suffering from mental ill health.

There is no difference in any of the insurance decision making processes for mental health to those for physical health. The process by which decisions are made and guidelines are written is consistent for every medical condition whether physical or mental health (or, as is often the case, a combination of the two).

Whether an individual has a mental health condition or not, if they are considering buying insurance, or just looking for more information, this article outlines some of the things individuals should think about.

As with any other form of insurance, check the small print for what is and is not covered, such as exemptions and exclusions.

When it comes to protecting and supporting individuals who have been diagnosed with a mental health condition, insurers will not only pay claims, they may also provide additional support.

Support services (generally) come at no extra cost and start from the day the cover begins. It is always there to help the individual, which means they can feel confident that help is always at hand. This help can include:

Many insurers provide specialist mental health service support, which enables employees of company schemes or individual policy holders to receive rapid access to assessment, often within 48 hours.

Individuals will often have a dedicated case manager/case management team assigned to them to take them through the whole process.

This can include a tailored treatment plan and access to a wide range of specialists including:

Most insurers have what are known as dedicated Employee Assistance Programmes (EAP) which provide access to support services 24 hours a day.

These can offer support on a range of topics which may trigger stress or anxiety, such as finances, relationships and legal issues, as well as dedicated mental health counsellors.

These services can be accessed through dedicated helplines as well as through interactive online services.

Rehabilitation services are at the heart of most protection insurance products, and consequently many insurers offer access to rehabilitation teams who help manage an employee’s or individual policy holder’s sickness absence.

They often offer access to counselling and a wide range of other services, including assistance with HR issues and legal assistance.

Many income protection policies have specific mental health pathways for individuals to get the tailored assistance they need it.

There are a range of insurance products that provide cover for a wide range of situations.

Although many people find that buying insurance provides financial security and peace of mind, which can help them on the road to recovery when the unexpected happens, it is important to understand the different products on offer and what they cover.

Some of the different types of insurance that an individual might like to consider buying that can provide financial peace of mind include:

For many insurance products, disclosing pre-existing mental health conditions is very important (A pre-existing medical condition is any condition an individual has at the time they apply for insurance).

Some insurance policies do not cover pre-existing conditions, meaning that they will not pay out on a claim related to a pre-existing condition (which can sometimes include mental health problems). For those who have been denied insurance cover due to a pre-existing mental health condition, look here for a list of specialist advisers on the Mind website (a mental health charity).

Insurers need to know about existing conditions as it allows them to understand the type of mental health condition, and the associated risk based on scientific evidence. As noted by research, mental health conditions can have a direct impact on a sufferer’s risk of premature death or disability and there are also links to greater risk of abuse of medication, drugs or alcohol, which increases the risk of a serious accident.

For most insurers, mental health will include all aspects such as:

Individuals will, generally, be asked to provide their diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment.

Regardless of an individual’s age or health status, they will need to provide information on their mental health and whether they have been diagnosed with or treated for a mental health condition.

Some insurers want individuals to disclose all mental health episodes regardless of when they occurred.

It is important that individuals disclose complete and accurate information because it affects the:

It is a legal requirement that individuals answer honestly, as failure to do so may result in the policy being void.

As noted above, insurance policies may or may not cover pre-existing medical conditions depending on the severity of the condition.

If an individual has been diagnosed, or has received treatment for a mental health condition, the insurer may want to know the following:

Some underwriters may split a question about an individual’s medical history into two asking:

There are a number of challenges an individual may need to consider, including:

There are a number of things that an individual can do to make sure they get the right cover for their needs.

Some companies provide cover specifically for people with pre-existing medical conditions, including mental health conditions. In order for an individuals to gain support that is specific to their needs, they may want to look into getting an insurance quote from a specialist provider (which can be found in Section 3.2 above).

Mental health support is of growing importance for UK businesses. Employers increasingly provide support which may include giving employees access to counselling services such as:

EAP services are confidential and can be accessed free without disclosure required to an individual’s line manager. Individuals may also be able to access occupational health support through their line manager or human resources service.

There are a vast range of questions an individual can ask, including:

The deferred period is the period of time from when a person has become unable to work until the time that the benefit begins to be paid. For example, an individual selected a deferred period of six months because they knew they would receive sick pay from their company for that period and would not need the insurance benefits.

The deferred period on income protection insurance is the period between going off work and the income payments commencing.

For example, income protection insurance with a 4 week deferred period will commence income payments once the policyholder has been off work for a period of 4 weeks.

The length of the deferred period is selected when the individual commences the income protection insurance, and this can be between 4 weeks and 12 months.

Generally, the longer the chosen deferred period the lower the monthly premiums on commencement of the policy.

Choosing a deferred period will be based on individual circumstances, taking into account the following two factors:

There is often confusion between the various types of insurance available on the market, particularly between income protection insurance and critical illness insurance (Section 9.0).

Income protection insurance is designed to provide an income if the individual is unable to work due to sickness, or as a result of an accident:

An individual may want income protection insurance:

Rehabilitation support services are typically bundled as part of income protection insurance and, although provision varies between insurers, example services include:

Critical illness insurance is a long term policy that will pay a lump sum if an individual is diagnosed with one or more of the critical illness detailed in the policy.

Reasons for taking out critical illness cover include:

Myth:

Only a few people get mental illnesses and they are unusual or odd, so it is obvious who they are.

Fact:

Mental health problems are common and we are often unaware of the person’s diagnosis.

Myth:

People with a diagnosis of mental illness are going to struggle for the rest of their lives.

Fact:

Most people recover from mental illness and go on to live fulfilling lives. Recovery is a unique and personal journey and often the person feels that they experienced personal growth and a new way of being through the process of recovery.

Myth:

People who attempt suicide or self-harm are doing it to get attention and are not really serious.

Fact:

All suicidal thoughts and self-harm, as well as all other forms and expressions of distress, are serious. Dismissing another person’s feelings as attention seeking only makes them withdraw from asking for help and may result in death or serious injury.

Myth:

People who have mental illnesses have brought it upon themselves, or their parents are to blame.

Fact:

Anyone can experience mental illness or experience mental distress regardless of their background or upbringing. Some people are more at risk through circumstances beyond their own control.

You must be logged in to post a comment.