1.0 Introduction

This article provides an overview of things that one might wish to consider regarding mental health and insurance.

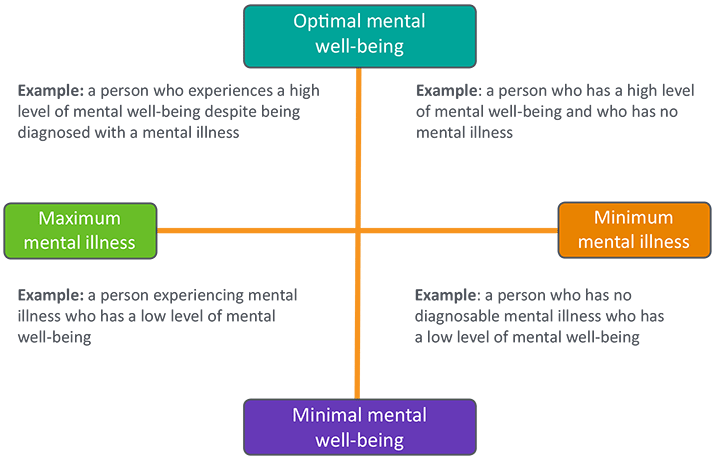

Mental health conditions might not be as easy to pin down as physical health conditions, but insurers are increasingly recognising the need to provide cover and support to those suffering with a mental health condition.

One in four people in the United Kingdom (UK) will be affected by a mental health problem in any given year and, of these, around four million will also struggle with their financial wellbeing.

The insurance industry is aware of the importance and value of insurance in protecting individuals when life does not go to plan. And, with this in mind, the insurance industry continues to demonstrate increasing commitment to aiding those suffering from a mental health problem. In 2017, mental health was the most common cause of claim on income protection policies in the UK.

The insurance industry continues to engage with the third sector (aka charities) and healthcare industries to promote greater access to insurance for individuals with mental health conditions and has repeatedly emphasised its commitment to aiding people suffering from mental ill health.

There is no difference in any of the insurance decision making processes for mental health to those for physical health. The process by which decisions are made and guidelines are written is consistent for every medical condition whether physical or mental health (or, as is often the case, a combination of the two).

Whether an individual has a mental health condition or not, if they are considering buying insurance, or just looking for more information, this article outlines some of the things individuals should think about.

As with any other form of insurance, check the small print for what is and is not covered, such as exemptions and exclusions.

2.0 Should You Bother Buying Insurance to Cover Mental Health Care?

When it comes to protecting and supporting individuals who have been diagnosed with a mental health condition, insurers will not only pay claims, they may also provide additional support.

Support services (generally) come at no extra cost and start from the day the cover begins. It is always there to help the individual, which means they can feel confident that help is always at hand. This help can include:

- Preventative Measures;

- Accessing Support Services; and

- Rehabilitation Services.

2.1 Preventative Measures

Many insurers

provide specialist mental health service support, which enables employees of

company schemes or individual policy holders to receive rapid access to assessment,

often within 48 hours.

Individuals will

often have a dedicated case manager/case management team assigned to them to

take them through the whole process.

This can include

a tailored treatment plan and access to a wide range of specialists including:

- Psychologists;

- Counsellors;

and

- Psychiatrists.

2.2 Accessing Support Services

Most insurers

have what are known as dedicated Employee Assistance Programmes (EAP) which

provide access to support services 24 hours a day.

These can offer

support on a range of topics which may trigger stress or anxiety, such as

finances, relationships and legal issues, as well as dedicated mental health

counsellors.

These services can be accessed through dedicated helplines as well as through interactive online services.

2.3 Rehabilitation Services

Rehabilitation services are at the heart of most

protection insurance products, and consequently many insurers offer access to

rehabilitation teams who help manage an employee’s or individual policy

holder’s sickness absence.

They often offer access to counselling and a wide range

of other services, including assistance with HR issues and legal assistance.

Many income protection policies have specific mental health pathways for individuals to get the tailored assistance they need it.

3.0 What Things Should I Consider before Buying?

There are a range of insurance products that provide cover for a wide range of situations.

Although many people find that buying insurance provides financial security and peace of mind, which can help them on the road to recovery when the unexpected happens, it is important to understand the different products on offer and what they cover.

3.1 Types of Insurance

Some of the different types of insurance that an

individual might like to consider buying that can provide financial peace of

mind include:

- Private Medical Insurance:

- This enables faster access to treatment by enabling a speedy diagnosis and reduced waiting times.

- It also helps to pay for some, or all, of the treatment that an individual may need.

- This can help the individual get back on their feet, and return to employment, quicker.

- Income Protection Insurance (Section 8.0):

- This will pay a tax-free monthly income while an individual is unable to work due to illness, injury and/or suffering a reduction in salary for a prolonged period.

- This insurance covers mental health issues and provides key support services.

- Travel Insurance:

- This covers the cost of any medical treatment an individual may need in an emergency when travelling abroad.

- Individuals can also obtain travel insurance which covers the cost of their holiday if they are unable to travel and need to cancel their holiday due to illness.

- Life Insurance:

- This is a type of policy that can be potentially affected by disclosure of mental health conditions.

- Find out more about the importance of disclosure below.

- Critical Illness Insurance (Section 9.0):

- Also known as critical illness cover, is a long-term insurance policy which covers serious illnesses listed within a policy.

- If an individual get one of these illnesses, a critical illness policy will pay out a tax-free, one-off payment.

3.2 Why is Disclosure Important?

For

many insurance products, disclosing pre-existing mental health conditions is

very important (A pre-existing medical condition is any condition an individual

has at the time they apply for insurance).

Some

insurance policies do not cover pre-existing conditions, meaning that they will

not pay out on a claim related to a pre-existing condition (which can sometimes

include mental health problems). For those who have been denied insurance cover

due to a pre-existing mental health condition, look here for a list of specialist

advisers on the Mind website (a mental health charity).

Insurers

need to know about existing conditions as it allows them to understand the type

of mental health condition, and the associated risk based on scientific

evidence. As noted by research, mental health conditions can have a direct

impact on a sufferer’s risk of premature death or disability and there are also

links to greater risk of abuse of medication, drugs or alcohol, which increases

the risk of a serious accident.

For

most insurers, mental health will include all aspects such as:

- Stress;

- Post-natal

depression;

- Attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD);

- Eating

disorders;

- Addictions;

- Myalgic

encephalomyelitis (ME), also known as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS);

- Fatigue;

- Depression;

and

- Anxiety.

Individuals

will, generally, be asked to provide their diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment.

Regardless

of an individual’s age or health status, they will need to provide information

on their mental health and whether they have been diagnosed with or treated for

a mental health condition.

Some

insurers want individuals to disclose all mental health episodes regardless of

when they occurred.

It is

important that individuals disclose complete and accurate information because

it affects the:

- Risk

assessment;

- Premiums

charged; and

- Terms

and conditions of their insurance policy.

It is a legal requirement that individuals answer honestly, as failure to do so may result in the policy being void.

4.0 What Information Might I Need?

As noted above, insurance policies may or may not cover

pre-existing medical conditions depending on the severity of the condition.

If an individual has been diagnosed, or has received

treatment for a mental health condition, the insurer may want to know the

following:

- Date of diagnosis;

- Method of treatment;

- Past methods of treatment;

- Doctor’s details;

- Symptoms and dates of last symptoms;

- Details of any previous hospitalisations;

- Specifics of time taken off work because of the

condition

Some underwriters may split a question about an

individual’s medical history into two asking:

- “Have you ever had…” for the more serious

incidents such as in-patient treatment or suicide attempts; and

- Just ask about the last five years for other

mental health issues, meaning if episodes happened before then, they may not

need to be disclosed at all.

5.0 What Challenges Might I Face?

There are a

number of challenges an individual may need to consider, including:

- Lack of Disclosure:

- Advisers

and insurers are used to dealing with medical conditions, both physical and

mental, so there’s no need for an individual to feel embarrassed about their

medical history.

- As with

all insurance applications, when an individual is applying for insurance it is

vital they are open and honest.

- A tiny

percentage of insurance claims are declined each year, but the main reason is

due to issues of non-disclosure at the application stage, for example individuals

omitting to say they are taking medication.

- High Risk Customer:

- Individuals

could be assessed as a ‘high risk’ customer which means that the insurance

provider believes that they are more likely to claim.

- As a

result, they may be charged a higher premium, or have a specific exclusion

added to their policy.

- Over the Phone rather than Online:

- Individuals

may be declined insurance if they try to apply for insurance directly online

and disclose that they have experienced a mental health condition or have an existing

mental health condition.

- It is

therefore recommended that individuals speak to a specialist adviser who will

be able to support their specific needs.

- Symptoms Change:

- If the

individual’s policy does not cover a specific mental health condition because

of a recent history of mental illness, yet they go on to be symptom-free for a

few years, it is worth reviewing the policy.

- Future cover

could be accepted at standard terms, which could save the individual money.

- The

insurance company’s adviser will be able to advise when will be the best time

to do this.

6.0 Where Can I Get Help? What Help is Available?

6.1 Who Can I Speak To?

There are a number

of things that an individual can do to make sure they get the right cover for

their needs.

Some companies

provide cover specifically for people with pre-existing medical conditions,

including mental health conditions. In order for an individuals to gain support

that is specific to their needs, they may want to look into getting an

insurance quote from a specialist provider (which can be found in Section 3.2

above).

Mental health

support is of growing importance for UK businesses. Employers increasingly

provide support which may include giving employees access to counselling

services such as:

- EAP;

- General

practitioner (GP) services;

- On-site

medical support; and

- Health

tracking apps.

EAP services are confidential and can be accessed free without disclosure required to an individual’s line manager. Individuals may also be able to access occupational health support through their line manager or human resources service.

6.2 What Questions Should I Ask Before Buying a Policy?

There are a vast

range of questions an individual can ask, including:

- Does the

plan cover mental health out-patient therapies or consultant sessions?

- How many

per year does the insurance cover?

- This

could include out-patient cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or a counselling

plan.

- At what

rate will the sessions be covered?

- Is there

a cost limit per therapy session?

- Is

approval required from the individual’s GP to access consultant or out-patient

therapies?

- Does the

individual need any pre-approval from the insurance company before they see a

mental health professional?

- Can the

individual get a list of providers in their area?

- Can the

individual meet with more than one provider for a consultation or second

opinion and still have it paid for?

- Does the

individual pay the provider or does the insurance company pay them?

- Are

psychiatric medications covered under the plan?

- Does the

policy cover substance abuse services?

- Inpatient

mental health services?

- Does the

policy also include self-help and guided online therapy?

- How many

days does the individual receive for in-patient/day-case mental health treatment

per year?

- Does the

insurance policy come with a counselling support service or specialist support

services? Examples include:

- EAP for

employer-based insurance products; or

- Individual

support from foundations such as RedArc – an organisation that includes a team of highly trained and

experienced Personal Nurse Advisers who provide practice advice and emotional

support.

7.0 What is a Deferred Period?

The deferred

period is the period of time from when a person has become unable to work until

the time that the benefit begins to be paid. For example, an individual

selected a deferred period of six months because they knew they would receive

sick pay from their company for that period and would not need the insurance

benefits.

7.1 What is a Deferred Period on Income Protection Insurance?

The deferred

period on income protection insurance is the period between going off work and

the income payments commencing.

For example, income protection insurance with a 4 week deferred period will commence income payments once the policyholder has been off work for a period of 4 weeks.

7.2 What is the Length of a Deferred Period?

The length of the

deferred period is selected when the individual commences the income protection

insurance, and this can be between 4 weeks and 12 months.

Generally, the

longer the chosen deferred period the lower the monthly premiums on

commencement of the policy.

7.3 How Do I Choose a Deferred Period?

Choosing a

deferred period will be based on individual circumstances, taking into account

the following two factors:

- Cover Provided by the Employer:

- If the individual’s employer pays them full sick pay for a period of time then it will make sense to set the deferred period from the date the sick pay ceases.

- This is because there is no point in setting the deferred period for less than the full sick pay period as the insurance company will not pay out until the individual ceases receiving income from their employer.

- If an individual requires cover for redundancy in their income protection policy, then they will need to take into consideration the amount of redundancy payment they will receive.

- For example, if the individual is likely to receive a redundancy payment equal to six month’s salary, then it would make sense to set the deferred period at six months.

- Personal Savings:

- If an individual has access to personal savings then it would make sense to factor this in.

- For example, if – in the event of sickness, accident or redundancy – the individual has enough personal savings to replace their income for three months, then set a deferred period of three months.

8.0 Income Protection Insurance

There is often confusion between the various types of insurance available on the market, particularly between income protection insurance and critical illness insurance (Section 9.0).

8.1 What is Income Protection Insurance?

Income protection

insurance is designed to provide an income if the individual is unable to work

due to sickness, or as a result of an accident:

- Benefits

will be paid until:

- The

individual returns to work;

- The end

of the policy (whichever comes first).

- Benefits

will only commence once a pre-agreed deferred period has passed.

- This

would generally be between one and twelve months.

- The

longer the deferred period the lower the premium.

- Income

protection insurance is a long term policy with premiums paid monthly.

- The

amount of income covered is typically 60-65% of the individual’s monthly income.

- Normally

enough to cover the mortgage and basic living expenses.

- Cover

may continue until retirement or prior cancellation.

- Any benefits

received are tax free.

- Unless

cover is provided free by an employer, in which case they may be taxed.

- Pre-existing

conditions are (normally) not covered under income protection insurance.

8.2 Why Would I Need Income Protection Insurance?

An individual may

want income protection insurance:

- If they

receive only statutory sick pay when off work;

- If they

only receive their full pay for a limited period of time when off work; and/or

- To make

sure their basic living expenses are covered whilst off work.

8.3 Rehabilitation Support Services

Rehabilitation

support services are typically bundled as part of income protection insurance

and, although provision varies between insurers, example services include:

- Rehabilitation Support:

- Early

intervention rehabilitation support services help individuals from the moment

they are unable to work due to illness or injury.

- The

insurer will provide assistance during the deferred period, and will source

specialist providers to suit the individual’s needs.

- Recuperation Benefit:

- The

insurer will pay for services requested by the individual that could improve or

maintain their health and help them return to work.

- This

could could range from physiotherapy or counselling through to help travelling

to work.

- The

individual could receive an additional payment of up to three times their monthly

income protection benefit with no deferred period.

- Hospitalisation Benefit:

- To help

individuals cope with long, expensive hospital stays, the insurer may pay individuals

a per night fee after a set number of nights (subject to a maximum number of nights).

- Proportionate Benefit:

- Returning

to work sometimes means a lower salary or fewer hours.

- The

insurer may top up the individuals benefit to match their usual monthly

earnings.

9.0 Critical Illness Insurance

9.1 What is Critical Illness Insurance?

Critical illness

insurance is a long term policy that will pay a lump sum if an individual is

diagnosed with one or more of the critical illness detailed in the policy.

- If paid

out the lump sum can also be used to provide a regular income.

- It is

designed to provide the money to pay off bills or make alterations to the

individual’s home, for example, wheelchair access.

- A

typical critical illness policy will cover conditions including:

- Conditions

like multiple sclerosis.

- All

illnesses have to be judged serious enough for the individual to qualify for a

pay-out.

- The

amount of cover is selected by the individual and not linked to income.

9.2 Why Do I Need Critical Illness Insurance?

Reasons for

taking out critical illness cover include:

- Providing the finances to support the individual’s family if diagnosed with a critical illness.

- Whilst life insurance will provide cover in the event of death (and can include cover which pays out if the individual is terminally ill with less than 12 months to live), critical illness insurance will provide the cover when the individual is critically ill.

- Providing peace of mind to the individual and their family.

You must be logged in to post a comment.